Caught between Trump and a liberal place

- Published

- comments

Donald Trump (R) met technology leaders when he was president-elect

California is a bubble. A rich, liberal, free-loving bubble.

It also just so happens to be the sixth largest economy in the world and home to the most influential, profitable and powerful companies on earth.

If the bubble bursts, or even just contracts a little, the whole country suffers - including President Donald Trump and his supporters. California is a so-called “donor” state, meaning it simply pays more into the US Treasury than it gets out.

So when President Trump talks about making deals, he’ll know full well that in California he faces formidable bargaining chips he can’t ignore. He may even be on the back foot.

And that may be one of the reasons why we saw a peculiar thing happen on Friday.

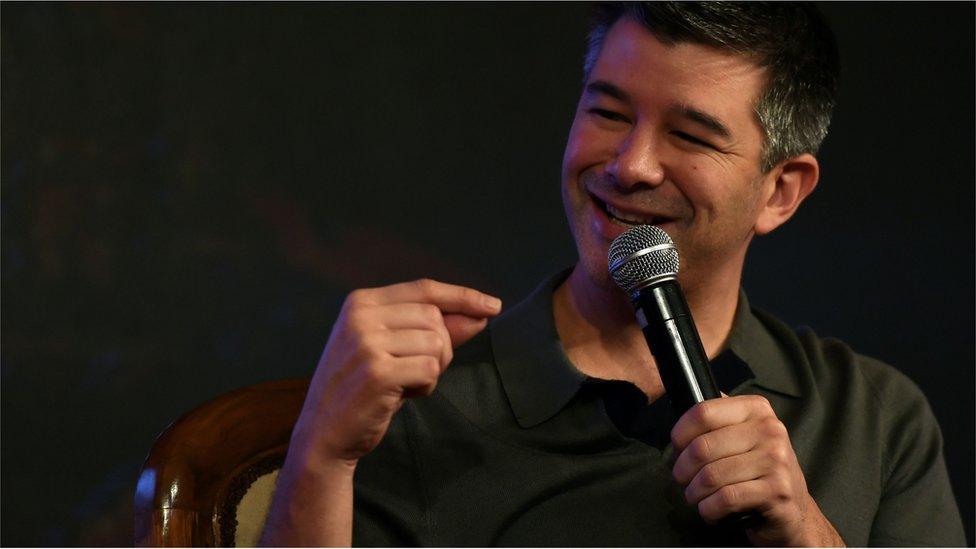

Uber boss Travis Kalanick decided not to turn up to President Trump’s economic advisory panel, and the president said... nothing.

He didn’t call the company “failing” or “once great” or “weak” or any of those words he’s typically thrown around when he feels personally slighted.

In fact, aside from a few pre-election skirmishes with Apple, President Trump has been relatively ambivalent towards tech firms, and there’s a very good theory as to why - he really needs them.

Travis Kalanick put Uber's reputation ahead of the value the company might get from a meeting with the president

And they need him too, of course.

Under President Trump, Silicon Valley is holding out for a lower corporate tax rate - which could bring billions back into the US, a win-win for both sides.

But there’s a snag in this arrangement. For the most part, the workers at these companies are outraged, seething at the prospect of their bosses even sitting at the same table as the new president.

That’s why we saw 2,000 Google employees across the world leave their desks on Monday to demonstrate against the immigration ban.

It’s why Amazon’s own employees are calling on the company to stop advertising on right-wing news website Breitbart, external.

It’s why Uber’s staff wrote a lengthy “Letter to Travis”, informing their boss about how unpopular his involvement with President Trump was among the ranks. It worked.

“Joining the group was not meant to be an endorsement of the president or his agenda but unfortunately it has been misinterpreted to be exactly that,” Mr Kalanick told staff in a memo announcing he was stepping down.

The tone was understanding, but a little frustrated. Would it not be better to at least have a seat at the table? Uber’s staff didn’t see it that way.

Mr Kalanick bemoaned what he called a “perception-reality gap”.

Although he said he didn’t support President Trump’s immigration policy, people thought he did. And that’s what mattered most.

He put Uber’s reputation ahead of the value Uber might get from a meeting with the president.

He may have been extra-sensitive after a long week.

Last Saturday, a misjudged tweet caused a reported 200,000 Uber users to delete their accounts - so many, in fact, the company had to create a special tool to automate the process.

Uber’s explanation that it was all a big misunderstanding has merit, but the furore, justified or not, underlined the fine line tech companies tread with their users.

The firms have until now acted in ways that were “good for business”, but now they are being forced to consider what is simply “good”.

One minute you can be helping the people of San Francisco get around, the next those same people are protesting outside your headquarters.

Twitter pressure

Another company tip-toeing along is Twitter, buoyed by its role as the mouthpiece for the most important man in the world, but cowed by what that man chooses to share.

It has faced calls to ban President Trump from the site, external on account of some feeling he has breached the network’s rules on hate speech and harassment.

It of course hasn’t done that - and to be fair, the demand didn’t gain significant traction, even amongst Trump’s opponents.

But Twitter’s employees, nervous about their role as President Trump’s megaphone, contributed a combined $1m (£800,775) to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).

The ACLU has been the benefactor of choice for companies that have one eye on public perception.

Many are dealing with what can be plainly described as the “Peter Thiel problem”. Mr Thiel, an investor with an arguably unrivalled track record, has his fingers in almost every significant pie around here.

And, uncomfortably for many, he also has the ear of the president, of whom he is an outspoken supporter.

When Facebook’s chief operating officer Sheryl Sandberg chose not to make a public statement on the Women’s March two weeks ago, people jumped to various conclusions, most of which inevitably led to the hand of Mr Thiel - who sits on Facebook’s board.

This comes despite any evidence Mr Thiel is calling any kind of shots on Facebook’s political position.

Support for President Trump in California is harder to come by than in other parts of the US

Meanwhile, well-regarded start-up accelerator Y Combinator is also feeling pressure thanks to its links with Mr Thiel.

The company’s president Sam Altman said he wouldn’t sever ties with the investor. The programme has said it will take on the ACLU as one of its cohorts, offering mentorship on digital projects.

It seems for now the rank-and-file of Silicon Valley see advising President Trump as indistinguishable from supporting him.

Technology companies are perhaps paying for years of hyperbolic statements about changing the world, in a place where a minor software update gets people “super excited”.

One thing that has struck me about staff at these huge companies is the infectious, passionate loyalty. It exists because those employees believe the company stands for the same issues they do. Any wavering creates shockwaves.

The atmosphere may get less toxic as the presidency continues, but it leaves bosses extremely hesitant to get around President Trump’s table.

Will President Trump need to get around theirs?

Follow Dave Lee on Twitter @DaveLeeBBC, external and on Facebook, external

- Published3 February 2017

- Published2 February 2017

- Published12 December 2016

- Published15 November 2016