Global manhunt for WannaCry creators

- Published

The malware has been taken apart by researchers seeking its creators

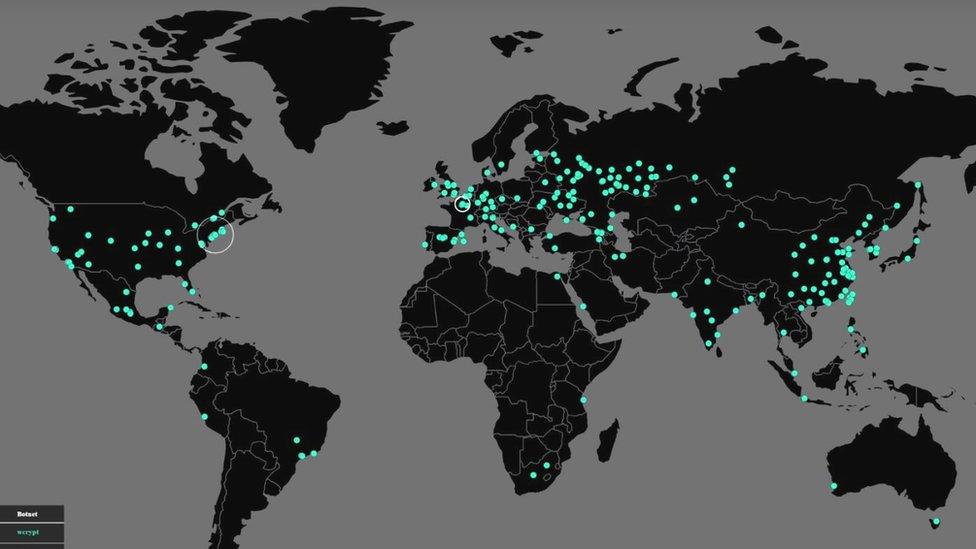

As organisations around the world clean up after being caught out by the WannaCry ransomware, attention has now turned to the people behind the devastating attack.

The malware uses a vulnerability identified by the US National Security Agency, but it has been "weaponised" and unleashed by someone entirely different.

So far, nobody seems to know who did it nor where they are.

Mikko Hypponen, head of research at security company F-Secure, said its analysis of the malware had not revealed any smoking gun.

"We're tracking over 100 different ransom Trojan gangs, but we have no info on where WannaCry is coming from," he told the BBC.

The clues that might reveal who is behind it are few and far between.

No Russians

The first version of the malware turned up on 10 February and was used in a short ransomware campaign that began on 25 March, external.

Spam email and booby-trapped websites were used to distribute WannaCry 1.0, but almost no-one was caught out by it.

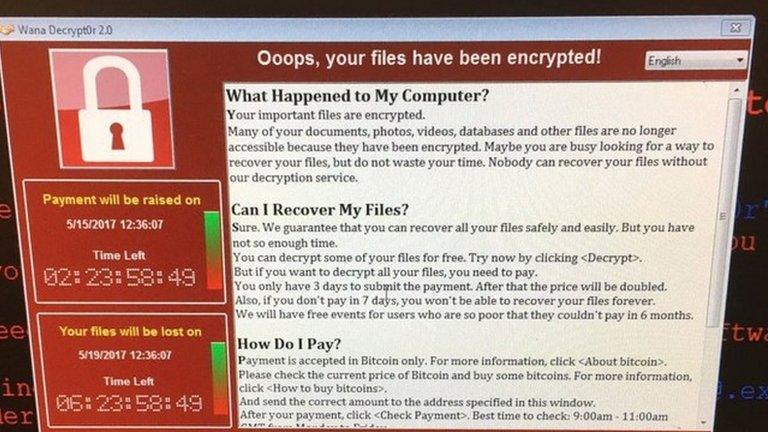

Version 2.0, which wrought havoc over the weekend, was the same as the original apart from the addition of the module that turned it into a worm capable of spreading by itself.

Analysis of the code inside WannaCry had revealed little, said Lawrence Abrams, editor of the Bleeping Computer security news website, which tracks these malicious threats.

"Sometimes with ransomware we can get a clue based on strings in the executables or if they upload it to Virus Total to check for detections before distribution," he said.

Those clues could point to it being the work of an established group, he said, but there was little sign of any tell-tale text in the version currently circulating.

"This launch has been pretty clean," said Mr Abrams.

The malware infects machines in Russia - a location lots of viruses avoid

Other researchers have noticed some other aspects of the malware that suggest it might be the work of a new group.

Many have pointed out that it is happy to infect machines running Cyrillic script.

By contrast, much of the malware emerging from Russia actively tries to avoid infecting people in its home nation.

Plus, the time stamp on the code suggests it was put together on a machine that is nine hours ahead of GMT - suggesting its creators are in Japan, Indonesia, the Philippines or the parts of China and Russia that are a long way east.

There are other hints in the curious ways that WannaCry operates that suggest it is the work of people new to the trade.

To begin with, the worm has been almost too successful, having hit more than 200,000 victims - many times more than are usually caught out by ransomware aimed at large organisations.

Administering that huge number of victims will be very difficult.

Whoever was behind it unwittingly crippled the malware by not registering the domain written in its core code.

Registering and taking over this domain made it possible for security researcher Marcus Hutchins to limit its spread.

There are other methods used to administer infected machines, notably via the Tor dark web network, and these addresses are being scrutinised for activity.

There are other artefacts in the code of the malware that might prove useful to investigators, said cyber-security expert Prof Alan Woodward from the University of Surrey.

In particular, he said, law enforcement might be probing use of the kill-switch domain to see if it was queried before the malware was sent out.

Other signifiers might be in the code for an entirely different purpose.

"It's often the case that many criminals put deliberate false flags in there to confuse and obfuscate," he said.

Tracking the movement of ransom payments might lead police to the attackers

Money talks

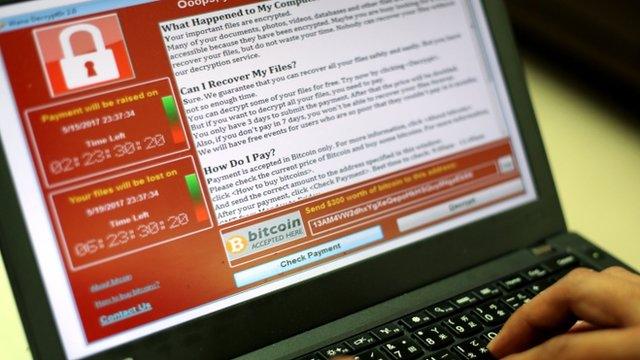

Also, most large-scale ransomware campaigns typically generate a unique bitcoin address for each infection.

This makes it straightforward for the thieves behind the malware to make sure they restore the files only of people who have paid.

WannaCry uses three hard-coded bitcoin addresses to gather ransom payments, and that is likely to make it challenging to work out who has paid, assuming the gang behind it does intend to restore locked files.

The bitcoin payments might offer the best bet for tracking the perpetrators, said Dr James Smith, chief executive of Elliptic, which analyses transactions on the blockchain - the key part of bitcoin that logs who spent what.

Bitcoin was not as anonymous as many thieves would like it to be, he said, because every transaction was publicly recorded in the blockchain.

This can help investigators build up a picture of where the money is flowing to and from.

"Ultimately criminals are motivated by money," he said, "so eventually that money is going to be collected and moved.

"The timing of that movement is going to be the big question, and we expect that will be down to how much gets paid in ransoms over the next few days."

Currently, the total paid to those bitcoin addresses is more than $50,000 (£39,000).

"Everyone is watching those addresses very carefully," said Dr Smith.

- Published14 May 2017

- Published13 May 2017

- Published15 May 2017

- Published15 May 2017

- Published14 May 2017