An alternative way to capture childhood on your phone

- Published

Parents are desperate to record childhood memories and the smartphone has allowed them to do this like never before. But what is the best way to go about it?

If all the videos you took of your children growing up were damaged and you could keep only the pictures or the sound, which would it be?

I liked to tantalise myself with this question before I had children, and I imagined surprising people by saying that - despite being a video journalist - I would choose the sound.

There is something more evocative about it, particularly the voice. To hear again a deceased relative, for example, is more arresting to me than to see a picture or silent video.

However, what I've actually found since becoming a parent is that there is another way of recording the fleeting moments of childhood, the results of which are more precious to me than either video or sound.

My preferred method still involves the smartphone, but it is focused on the power of words.

To explain the inspiration behind my method I need to recall my own childhood.

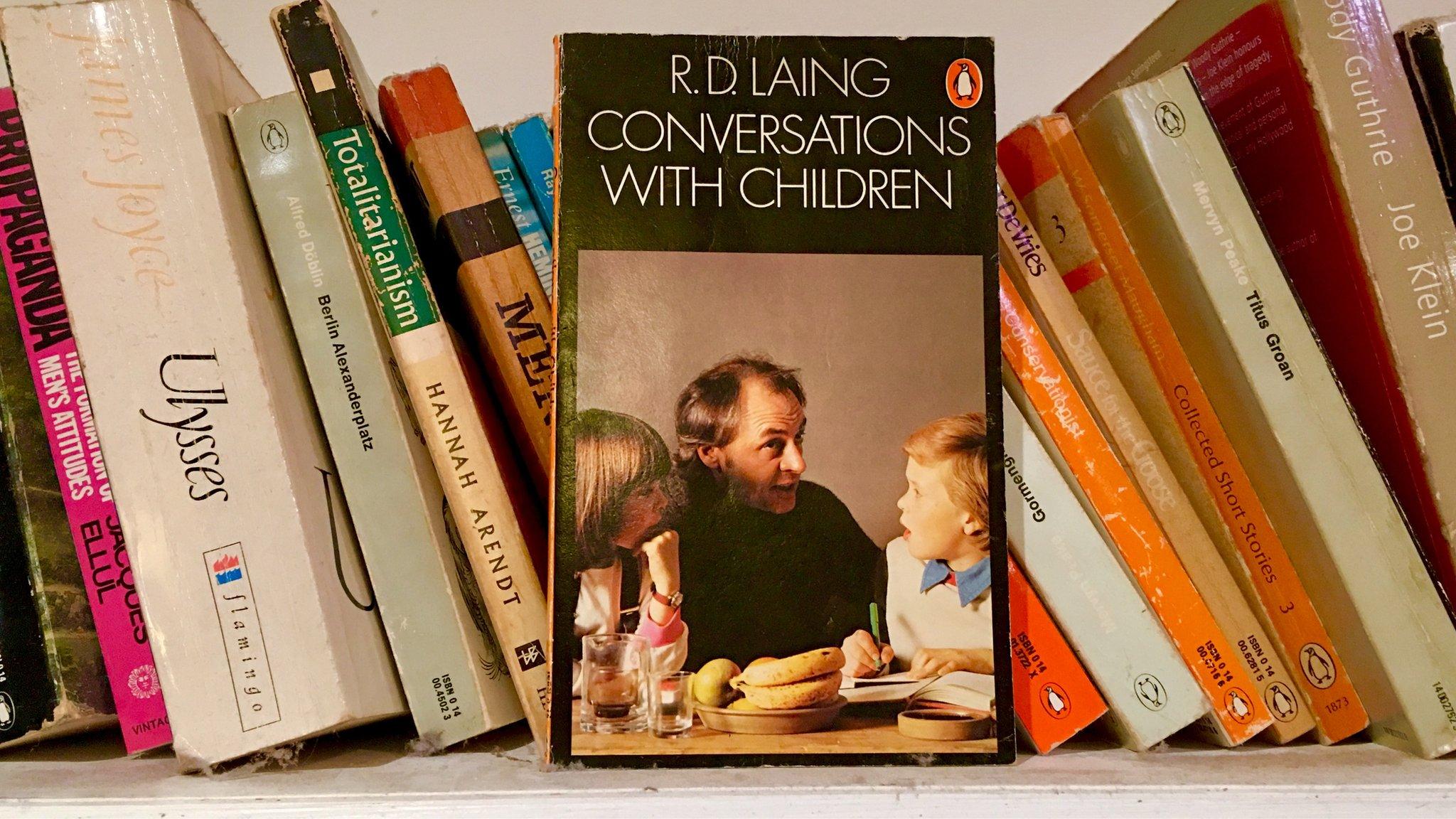

When I was around 10 or 11 years old, I became intrigued by a book I found on my parents' bookshelf.

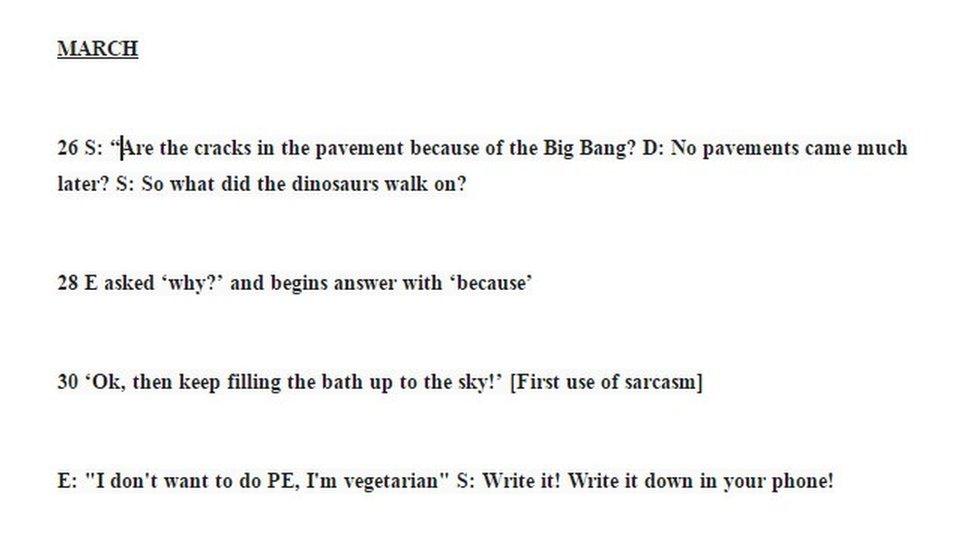

It was called Conversations with Children, an anthology of transcripts made by a child psychologist called R D Laing, who recorded what his children had said.

It was full of all the wonderful, crazy, uninhibited ideas you might expect. It was both entertaining and thought-provoking because Laing took the chance to explain the common patterns of emotional and intellectual development experts find in children.

He explained how during childhood we gradually come to understand concepts that determine our place in the world and what is possible within it: size, geography, time, empathy, ownership, societal norms, death.

I determined that when I had children I would record something similar myself.

R. D. Laing's 'Conversations with Children' was a bestseller first published in 1978

In 2009 I acquired my first child and Steve Jobs's third iPhone.

So I was part of the first generation of parents to have easy access to a stills camera, video recorder, audio recorder and digital notepad all in one handy device.

The early iPhones, having a fairly low resolution, didn't capture video very well. But in any case, when my daughter started to speak her first words, I found that I had a strong impulse to write down what she said rather than film her - remembering Laing's inspirational book.

To begin with, I wrote her early words in an ornate, hardback book that I bought specially for the purpose, befitting the words' importance, I thought.

But this presented problems. I soon became worried about losing it. And it took time to find it when there was something to write down, meaning I might forget what had been said in the meantime.

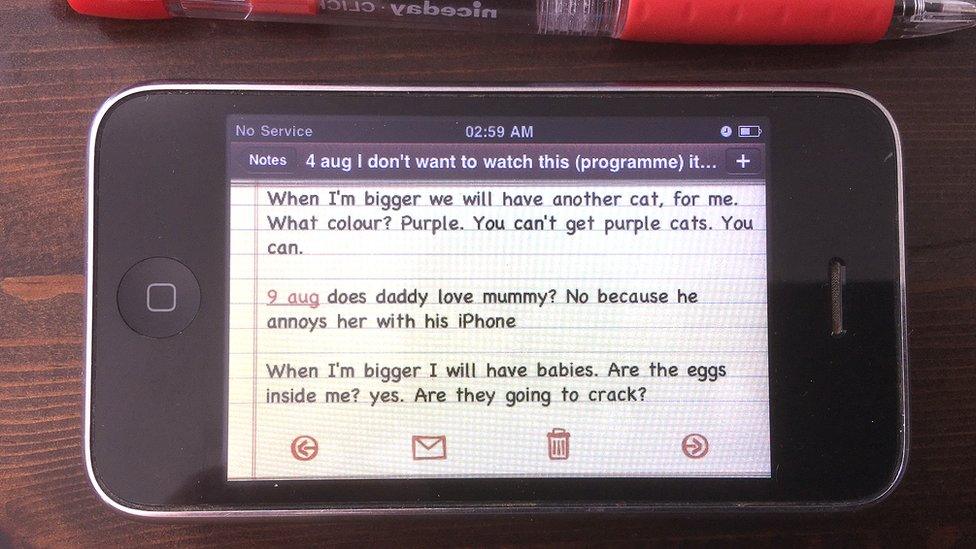

I found it more convenient to write down the words in the Notes app of my iPhone, which I could always whip out of my pocket. Once a month or so I could email the notes so I had a back-up copy. Later, cloud computing would help.

I had never in my life kept a diary, but suddenly it felt vital to record the experiences unfolding around me as accurately as possible.

Some pitfalls immediately became apparent on appointing myself the family's digital scribe and archivist.

My fumbling on the phone was sometimes misconstrued as untimely and indulgent internet surfing - an injustice when I was actually engaged in the noble task of recording events for posterity. You have to disengage temporarily from family life to make a decent stab of recording it accurately.

Of course I wanted to keep as accurate a record as possible.

But can words, recalled by a human, be as reliable as recorded video or sound?

One thing I've found from hours spent filming and recording audio at work as a BBC News video features journalist is that the most poignant moments are very difficult to capture.

You are lucky to have the mechanical equipment on and recording during that telling event that unfolded so quickly around you.

But by using that capturing device that is always on but invisible, known as our memory, any event, any candid, revelatory moment that unfolded suddenly out of the mundane, can be recorded and cherished.

The trade-off is you lose the 100% mechanical guarantee of accuracy.

There have been times when something wonderful was said so perfectly by my children, that I was determined to write down their precise words at the first opportunity.

But inevitably I would be confounded by a thousand preoccupations that looking after children throws your way, resulting in the mental agony that I couldn't guarantee to myself that I'd recorded the words correctly.

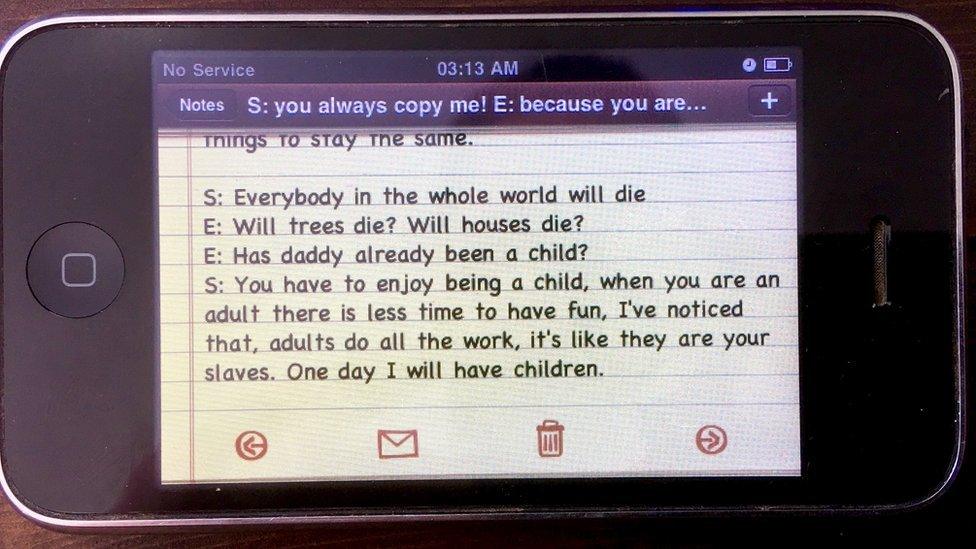

Longer, drawn-out conversations, of course - like an argument between two siblings over who has the larger spoon at breakfast - can't, unfortunately, be recorded verbatim.

Unnatural reactions

Another issue I've encountered at work is the reaction of humans to being recorded.

As soon as the red light is on and the subject is invited to speak, everybody to some extent acts unnaturally, from the member of the public (nervous) to the media-trained professional (too polished, verbose and over-confident).

The most revealing comments - even when a story is completely uncontroversial - are made off-camera, when a person is relaxed and has forgotten the recording device is there.

This doesn't matter for the uninhibited toddler. But certainly from around five years old, a child has developed enough self-consciousness and a sense of identity to change behaviour when they realise they are being filmed for others and for posterity.

You can tell this from the way they now produce a staged smile for a photograph.

This phase of child development is recorded in my own notes.

I begin to find references, from around the age of five, to the whole note-recording process, including requests for things to be written down because the subjects themselves realise what they have said is funny or otherwise noteworthy.

Occasionally there is an objection to the whole enterprise, for being embarrassing or boring.

Of course I'm sure I'm not the first parent to have written down the choice words their children have spoken.

But I am one of the new generation to benefit from having the smartphone to aid the enterprise.

In an age when parents are obsessively filming, photographing and sharing to social media, I think it's worth remembering the power of this simpler, in some ways more intimate, method.

It's something I came to appreciate even more as I witnessed my children learning to read and write themselves: the joy of being absorbed in a book you are devouring, the creative possibilities opened up by writing.

Both are so much more fulfilling than passively consuming an endless stream of games and videos on a mobile device.

Future-proof

Recording childhood through a digital record of words also carries some practical benefits. It avoids the nightmare of trying to sync videos from your phone and then organise and archive them in a safe place.

And it is also more future-proof, because you have to wonder whether, in decades' time, the video file formats you used will still be readable.

Today my children are nine and seven years old. The endearing, hilarious, uninhibited, sweet, surreal words still flow - although now they are more of a manageable trickle.

My book stands at 135 pages long.

When I look back on the notes, the power of these words is already greater than I could have imagined when I started the project.

To reread them stirs memories, recalling sights and sounds from the moment they were spoken, in a very vivid way.

Perhaps one day when I am frail in a care home this most precious book can be read to me.

Perhaps by my own children, if they visit.

And they will know that I was there and I heard every word.

And that I cared enough to record it.

You can follow Dougal Shaw on Twitter: @dougalshawbbc, external

You may also be interested in: