The computers being trained to beat you in an argument

- Published

Humans are used to being outdone by computers when it comes to recalling facts, but they still have the upper hand in an argument. For now.

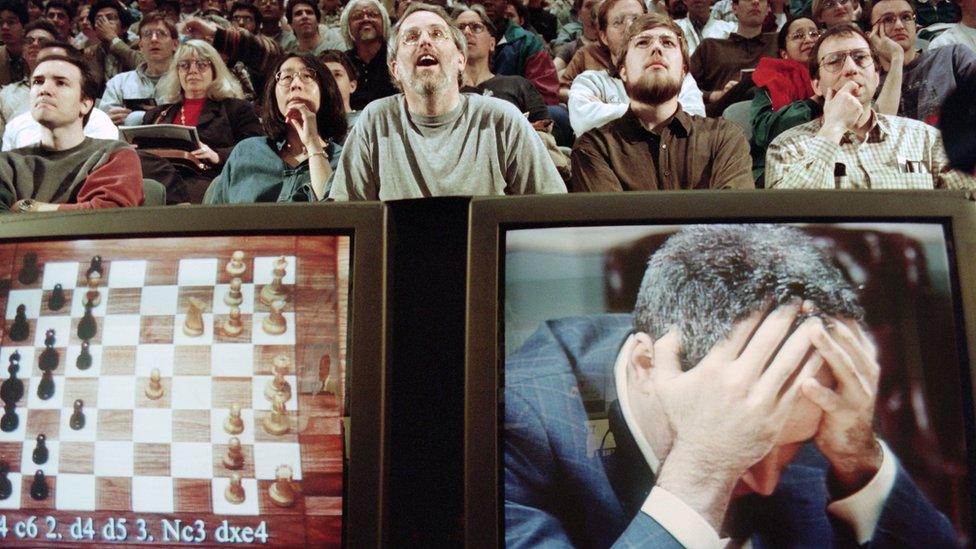

It has long been the case that machines can beat us in games of strategy like chess.

And we have come to accept that artificial intelligence is best at analysing huge amounts of data - sifting through the supermarket receipts of millions of shoppers to work out who might be tempted by some vouchers for washing powder.

But what if AI were able to handle the most human of tasks - navigating the minefield of subtle nuance, rhetoric and even emotions to take us on in an argument?

It is a possibility that could help humans make better decisions and one which growing numbers of researchers are working on.

Argument spotting

Until very recently, the creation of machines that can argue was an unattainable goal.

The aim is not, of course, to teach computers how to up the pressure in a feisty exchange over a parking space, or to resolve whose turn it is to take out the bins.

Instead, machines that can argue would inform debate - helping humans challenge the evidence, look at alternatives and robustly draw conclusions.

It is a possibility which could advance decision making on everything from how a business should invest its money, to tackling crime and improving public health.

But teaching a computer how people communicate - and what an argument actually is - is extraordinarily complex.

World Chess champion Garry Kasparov lost to the computer Deep Blue in 1997

Think about a courtroom as an example of where arguments are central.

Giving evidence is certainly a part of the process, but social rules, legal requirements, emotional sensitivities, and practical constraints all influence how advocates, jury members and judges formulate and express their reasoning.

Over the past couple of years, however, researchers have started to think that it might be possible to model some aspects of human arguments.

Work is now under way to capture how such exchanges work and turn them into AI algorithms.

This is a field known as argument technology.

The advances have been made possible by a rapid increase in the amount of data available to train computers in the art of debate.

Some of the data is coming from domains like intelligence analysis, external; some from specialised online sources, external and some from broadcasts such as the BBC's Moral Maze.

New methods to teach computers how arguments work have also been developed.

Researchers in the area draw on philosophy, linguistics, computer science and even law and politics in order to get a handle on how debates fit together.

At the University of Dundee, external we have recently even been using 2,000-year-old theories of rhetoric as a way of spotting the structures of real-life arguments.

The rapid advances in the field have led to dozens of research labs around the world applying themselves to the problem, and the explosion in this area of research is like nothing else I have witnessed in 20 years in academia.

'Why is the sky blue?'

Does this mean that computers will soon be fluent orators on the verge of taking over the world?

No. Let me give you a mundane example.

Until very recently even the most sophisticated AI techniques would have been completely flummoxed by pronouns.

So if you say to your smartphone's personal assistant: "I like Amy Winehouse. Play something by her," the software would be unable to work out that by "her" you mean "Amy Winehouse". Hardly the stuff of robot-apocalypse nightmares.

Computers could learn to master the kind of 'why?' questions beloved of toddlers

If such simple things can be too difficult for AI, what chance is there that computers could argue?

Narrowing our focus down, there are at least two ways in which computers could argue that are tantalisingly close.

The first is in justifying and explaining.

It's one thing to look up online how video game violence affects children, but it's quite another to have a system automatically harvest reasons for and against censorship of such violence - an area being explored by IBM, external, with whom we collaborate.

The system that results is like an assistant, making sense of the conflicting views around and allowing us to dig into the justifications for different standpoints.

The second is to develop artificial intelligence that can play dialogue games - following the rules of interaction that can be found everywhere from courtrooms to auction houses.

These games have been a mainstay of philosophical investigation from Plato to Wittgenstein, but they are starting to be used to help computers contribute to discussions between humans.

Find out more

Two special programmes using argument technology to assess debates marking the 50th anniversary of the Abortion Act will be broadcast by the BBC in October.

An episode of the Moral Maze will be aired on BBC Radio 4 at 20:00 BST on Wednesday 11 October, with analysis by the Centre for Argument Technology available immediately afterwards.

A BBC Two documentary called Abortion On Trial will be broadcast at 21:00 BST on Monday 16 October and followed by argument technology analysis that joins up the debate across the two programmes.

Anyone who's met a toddler will be familiar with one of these games.

The rules are very simple. The adult says something. The toddler asks, "Why?" The adult answers. The toddler asks, "Why?" again. And repeat.

Usually these conversations end when the adult makes a desperate attempt to change the subject.

But most of us who've played this game in the role of the adult will know that, actually, after a couple of moves, it can become rather difficult to give good answers: we have to think pretty hard.

Thinking pretty hard - while not terribly important if trying to explain to a three-year-old why the sky is blue - becomes much more important if the discussion is about a business decision affecting hundreds of jobs, or intelligence on whether a group poses a terrorist threat.

So if even the simplest possible dialogue game might be able to improve thinking around important decisions, what about more sophisticated models?

That's what we're working on.

If computers can learn the techniques to identify the types of argument humans are using to make group decisions, they can also assess the evidence used and put forward suggestions, or even possible answers.

Helping a team to avoid unconscious biases, weak evidence and poorly thought-through arguments can improve the quality of debate.

Artificial intelligence could help to inform anti-terrorism strategies

So, for example, we are building software that recognises when people use arguments based on witness testimony, and can then critique them, pointing out the ways in which witnesses may be biased or unreliable.

From corporate boardrooms, to couples' mediation and from intelligence analysis to interior design, AI could soon be helping to nudge us towards better decisions.

The term "artificial intelligence" was first used in the late 1950s and leading researchers at the time confidently predicted that full AI was about 20 years away.

It still is - and probably much farther away than that.

In the meantime, argument technology offers the potential to contribute to the decisions made by humans.

This type of artificial intelligence would not usurp human team members, but work with them as partners to tackle difficult challenges.

And it might even offer help explaining to three-year-olds why the sky is blue.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Prof Chris Reed is the director of the Centre for Argument Technology, external at the University of Dundee.

The centre has received more than £5m in funding, with backers including the Engineering and Physical Science Research Council, Innovate UK, the Leverhulme Trust, the Volkswagen Foundation and the Joint Information Systems Committee.

It focuses on translational argumentation research from philosophy and linguistics to AI and software engineering.

Edited by Duncan Walker