Security warning over hospital syringe pumps

- Published

The pumps are used in many different ways, including keeping patients unconscious during surgery

Syringe pumps used in hospitals around the world have flaws hackers could exploit to change the dosages being delivered to patients.

Security researcher Scott Gayou found eight separate flaws in the MedFusion 4000 pump made by Smiths Medical.

His discovery led the US Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to issue a warning, external about the danger this posed.

Smiths plans to fix devices by early 2018 and said it was "highly unlikely" any hackers would exploit the flaws.

Complex condition

The wireless infusion pumps studied by Mr Gayou are used in hospitals to administer precise doses of drugs, blood, antibiotics and other critical fluids to patients.

They are also used during surgery to ensure patients stay unconscious, and in neonatal wards to treat premature babies.

The vulnerabilities found by Mr Gayou left the devices open to a series of well-known attacks as they did little to check who was connecting to them and did a poor job of sanitising any commands they were sent.

The DHS said anyone successfully exploiting the vulnerabilities could "gain unauthorised access and impact the intended operation of the pump".

This, it said, could let attackers hijack the pump's communications and control systems.

The DHS acknowledged that there were no "known public exploits" that explicitly targeted the vulnerabilities, but it said hospitals should look at how they used the pumps to see what risk they posed.

In a statement,, external Smiths said the risk of the vulnerabilities causing any harm was low because they required a "complex and an unlikely series of conditions" to be met before an attacker could abuse them.

Prior to issuing a software update in January 2018 that will aim to fix the vulnerabilities, it also gave advice about how to change the set-up of the affected pumps to further limit the chance they would be exploited.

It apologised for any inconvenience the discovery had caused customers.

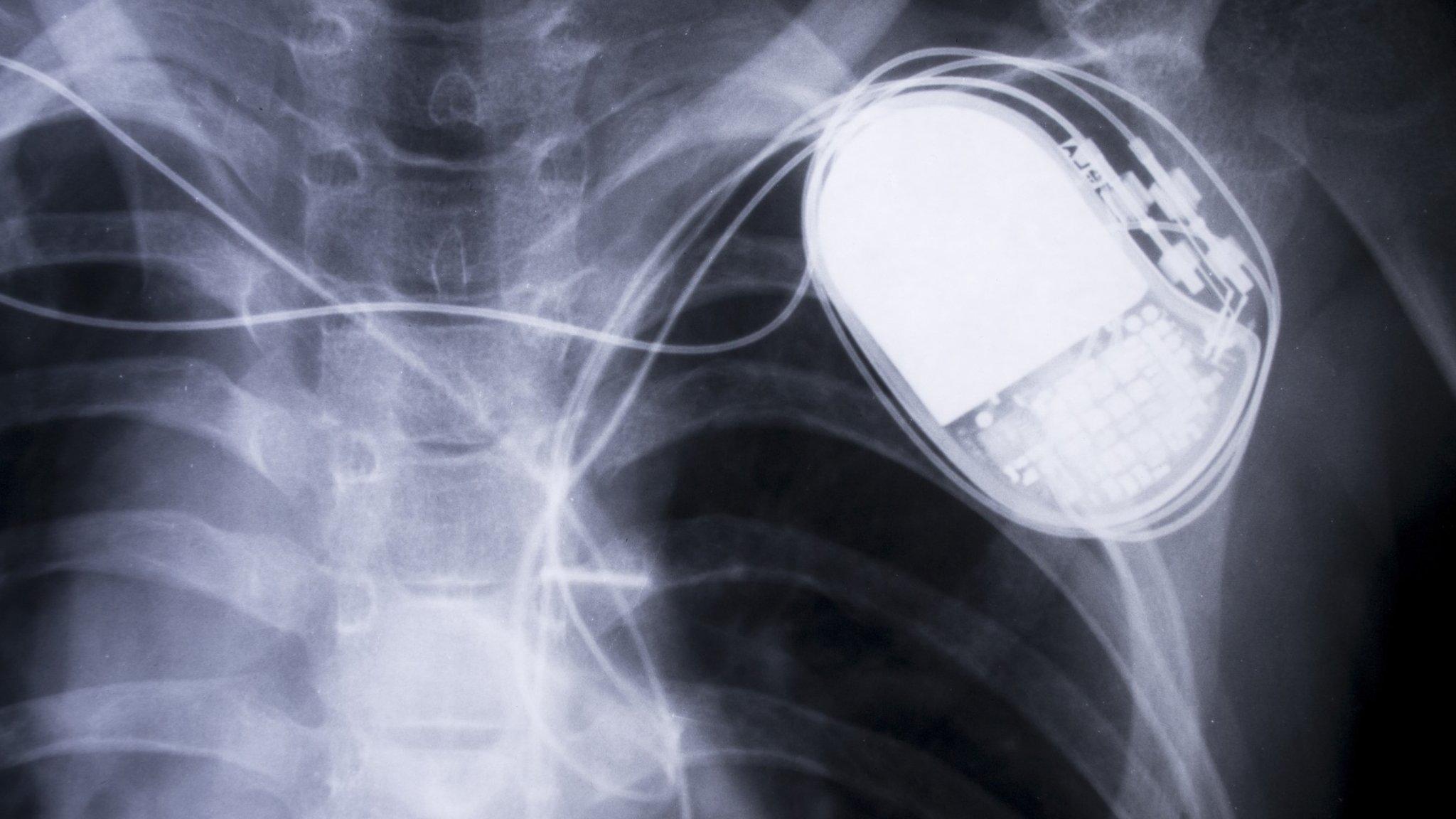

The analysis of the pump software comes soon after flaws were found in more than 745,000 pacemakers that, if exploited, could lead to them being hacked.

- Published24 August 2017

- Published30 August 2017

- Published25 May 2017

- Published13 July 2017