Tech Tent: Kaspersky and the Kremlin

- Published

Stream or download, external the latest Tech Tent podcast

Listen to previous episodes on the BBC website

Listen live every Friday at 15:00 BST on the BBC World Service

On this week's Tech Tent we talk to the founder of the Russian cyber-security firm banned by the US government. We also look at whether Apple is taking a big risk by pushing the price of its latest iPhone so high, hear how an app helped save victims of flooding in Texas and discuss whether there is a better way for companies to store data and keep our information safe.

Eugene Kaspersky believes his company is being smeared

Safe and security

Eugene Kaspersky is a buccaneering figure, proud of his achievements in building a thriving anti-virus firm over the last 20 years and never shy about giving his opinions at industry conferences.

But now the firm he founded has to face up to a crisis in a key market after the Trump administration banned the use of his products by US government agencies

When we spoke to him, he seemed to think that his company was the victim of a smear campaign: "Someone is using this situation, turning their aggressive PR against my company."

Earlier this summer, one American security researcher suggested the company could be ordered by the Kremlin to send out a "malicious update", threatening American computers. Mr Kaspersky dismisses that idea as "science fiction" and insists his firm does not have close ties to the Russian intelligence services.

He tells us "everyone spies on everyone" and his firm just wants everyone to work together against the threat of cyber-crime.

But given the current state of relations between Russia and the United States, Mr Kaspersky's hopes that peace, love and understanding will break out look far-fetched.

Some critics believe the iPhone X makes the new iPhone 8 models look outdated

Small steps

"Every once in a while a revolutionary product comes along that changes everything." That quote from Steve Jobs at the launch of the iPhone seemed overblown at the time - but proved to be correct.

But when Tim Cook said this week that the latest version was the biggest leap forward since the original iPhone, it seemed an outlandish claim.

The iPhone X may have facial recognition, and a screen that goes right to the edge, but neither feature is exclusive to Apple - although the company prides itself on better execution of new technologies than its rivals.

Brian Merchant is not convinced that the new device is all that revolutionary. He is the author of The One Device, a compelling account of the birth of the iPhone. It will amuse iPhone users, who have found it less than perfect at actually making phone calls, to know that Steve Jobs was initially driven to launch the project by his frustration with the call quality of his mobile phone. On one occasion he smashed his device against the wall in frustration.

Mr Merchant says the iPhone X is a very nice device but "not in the same arena, the same area code as the original iPhone".

He believes Apple is now facing the classic innovator's dilemma - its phone is so successful and is so hugely profitable that the company is loathe to take risks on some radical new product.

The other question is whether a strategy of releasing the iPhone X two months after the new iPhone 8 models could backfire. There is a risk that wealthy early adopters determined to have what Apple says is the future of phones will wait until November, while the rest will decide that the iPhone 8 is already out of date and they might as well stick with what they have for a bit longer.

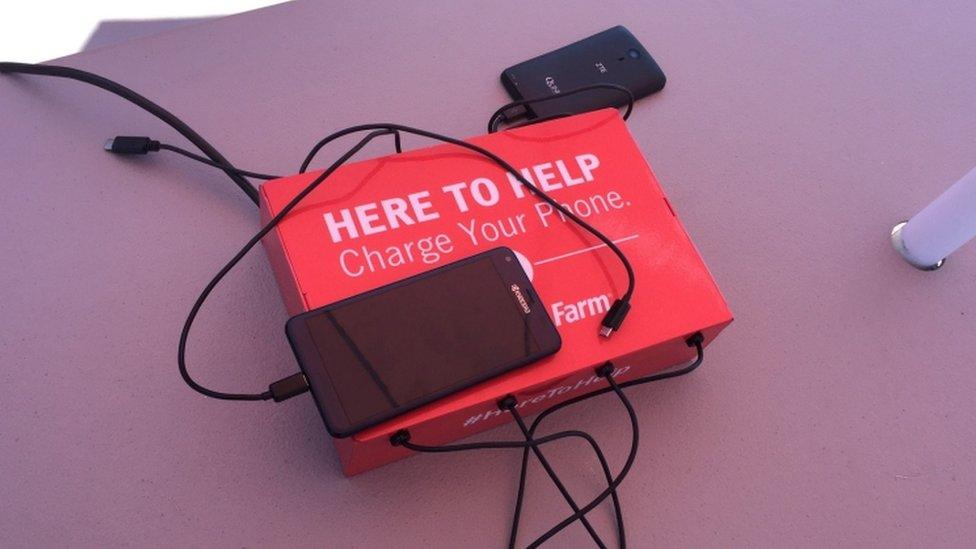

Many found their smartphones invaluable during in the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey

Rescue tech

It seems in every crisis or natural disaster, a new form of communication proves its worth. It was the telegraph which brought news of the sinking of the Titanic, while more recently mobile phones and then social media have given victims and rescuers ever faster and more efficient ways of spreading information.

During the recent hurricane and flooding in Texas, an app called Zello which turns a phone into a sort of walkie-talkie was widely used by people trying to get help.

Holly Hartman, a teacher at Memorial High School in Houston, used the Zello app to help co-ordinate rescue efforts.

She told Tech Tent that thousands of people trapped in their homes had used Zello to try to contact the emergency services and volunteers like her.

"I think the reason it's better is it's immediate," she says, "you just push the button and you're there."

But what made Zello work was that another volunteer collated all of the information it generated on an online map, allowing everyone to see where help was needed most urgently.

Ms Hartman found herself in the middle of some heartrending stories - a young boy called in great distress to say his two brothers had been electrocuted in the floodwaters and a woman sought help for her 87-year-old grandfather stranded at home as the waters rose. In both cases, the rescue boats eventually managed to reach them.

But all of this was only possible because the telecoms infrastructure survived the flooding - the Zello app does not work without some kind of data connection.

The credit rating firm has been under fire over its handling of the data breach

Equifax and figures

This week has seen the anger over the data breach at the credit-scoring firm Equifax grow ever more intense, as questions about just whose information is at risk and why the firm's defences failed remain unanswered.

One American politician called it the biggest corporate scandal since the collapse of the energy firm Enron. It also highlights the danger inherent in the practice of pooling vast amounts of personal data in one place.

The British entrepreneur Nick Halstead believes we need to decentralise data. His company Infosum has invented a system which he claims means data can be pooled without actually moving it around. His software allows users to interrogate data held elsewhere at a group level without ever grabbing hold of the information of any individual.

He tell us that the Equifax model which involves buying up credit information on all of us from sources around the world is dangerous. "If they used a decentralised technology then they would not need to bring that data into the centre of Equifax which could then get leaked," he said.

The big data revolution has been endlessly hyped with companies convinced that the more of this oil of the information era they acquire, the richer the insights they will garner, enabling them to outpace their rivals. But as Mr Halstead points out, while our capacity to pool and store data has grown rapidly, we have not learned much about keeping it secure.

- Published14 September 2017

- Published13 September 2017

- Published8 September 2017