Tech Tent: Should reality be virtual or augmented?

- Published

Stream or download, external the latest Tech Tent podcast

Listen to previous episodes on the BBC website

Listen live every Friday at 15:00 BST on the BBC World Service

What kind of reality do we want to live in - a virtual or augmented world? Two of the most powerful men in the technology world disagreed this week on whether VR or AR was the answer. On Tech Tent we discuss which technology is winning. We also hear from teenage tech award winners with an optimistic view of women's place in the technology industry, and we meet the founder of Evernote who tells us why the world has fallen out of love with Silicon Valley.

High prices have meant VR headsets have not sold in huge quantities

VR v AR

Over the past couple of years, huge sums have been invested in virtual reality, with the promise that this time the technology is ready to enter the mainstream.

But while the likes of Oculus, Samsung, Sony and HTC have all launched headsets, sales have so far failed to match the hype.

This week Mark Zuckerberg unveiled plans for a new, cheaper Oculus headset - Facebook bought the business back in 2014 - and insisted that virtual reality was going to be huge: "The future is built by the people who believe it can be better," he declared.

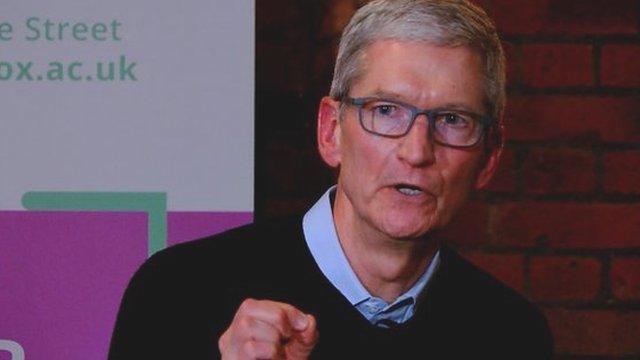

At almost exactly the same moment Apple's Tim Cook was being interviewed at Oxford University and told a student that AR - augmented reality where virtual objects are imposed on the real world - was the future because it allowed a more human connection.

"I've never been a fan of VR because it does the opposite," he said. "There are clearly some cool, nichey things for VR but it's not profound - AR is profound."

One of those cool "nichey" VR things could be its use by businesses to help train people. We visited London firm Immerse which is developing products for the new Oculus Business division and is already working with companies like DHL and Inmarsat.

I strapped on a headset, picked up two handheld controllers and found myself in the middle of a desert being taught to assemble a satellite dish by a trainer who was in the next room but could have been thousands of miles away.

Justin Parry of Immerse says there is growing enthusiasm among businesses for the way virtual reality can cut the costs of training a global workforce, among other applications.

And surprise, surprise, he rejects Tim Cook's view that augmented reality is superior:

"AR can't take you to other places in the way VR can, it can't create the same degree of impossible that VR can."

Mark Zuckerberg's virtual trip to a devastated Puerto Rico misread the public mood

Silicon Valley at the crossroads

"The truth is it's not that big and important a place in the scheme of things." That is what Phil Libin tells us about Silicon Valley.

The founder of Evernote, who is now running an incubator focused on artificial intelligence, is one of the more thoughtful tech entrepreneurs. When I talked to him about the change of mood towards Silicon Valley, with mounting criticism of its culture, he felt that it had always had an exaggerated sense of its own importance.

But Mr Libin says that lots of places have many of the things you need to build great technology - he gives Mexico City as one example - but haven't created a Facebook or a Google. What they lack, he explains, is the venture capitalists, the lawyers, the regulations that nurture small business:

"We have this talent in Silicon Valley for making small companies. We've exported that idea and somehow we got the whole world to believe that the real thing you have to do is make small companies"

Until very recently, it seemed that politicians in particular were in awe of the global tech capital, convinced that it had constructed some kind of innovation utopia, that its entrepreneurs were uniquely gifted and wise.

Now they are often seen as elitist and out of touch. Mark Zuckerberg's ill-fated virtual reality trip to Puerto Rico this week was just one example of that.

Mr Libin thinks other places could now learn how to find better ways of creating exciting new products. But don't bet against Silicon Valley - for 60 years it has shown it can adapt to changing economic and cultural trends.

Ada Lovelace was a pioneering mathematician and nascent programmer

Girls in tech

Last Tuesday was Ada Lovelace day - named after the woman now recognised as the first software programmer. It's an annual celebration of women who've achieved great things in technology.

But around the world there's concern that too few girls are seeing a career in science or technology as an attractive option.

This week in London I found some cause for optimism - at Buckingham Palace of all places. The Teentech Awards encourage schools from across the UK and now several other European countries to build projects showing off their tech expertise,

The winners went to the Palace to collect their awards - and more than half of those getting their certificates from the Duke of York were girls.

But speaking to some of them about their view of technology, we found some stereotypes hard to shift: "Maybe because they are more into make-up, drama, all that kind of stuff," said Molly from Glan-y-Mor school when I asked her why there were fewer women going into tech jobs.

Mind you, she and her fellow winners told me they did not believe science subjects were just for "nerdy" boys, and many of them were hopeful that they could have a future in the technology industry.

What they seemed to be missing was a role model. None of them could name a famous woman in science or technology. Ada Lovelace day gets bigger each year and its organisers do an excellent job - but there's plenty more to be done.

- Published10 October 2017

- Published11 October 2017

- Published11 October 2017