UK seeks future cyber-security stars

- Published

Bletchley Park is host to a centre developing cyber-based lessons for school pupils

A £20m initiative to get schoolchildren interested in cyber-security has been launched by the UK government.

The Cyber Discovery programme is aimed at 14 to 18-year-olds and involves online and offline challenges themed around battling hackers.

It is one of several programmes trying to build interest in security work and help fill a looming skills gap.

One industry expert said a broad strategy would be needed to address the widening gap.

Hacker clubs

The free Cyber Discovery programme aims to "encourage the best young minds into cyber-security", said Karen Bradley, Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, in a statement.

Young people interested will be asked to enrol via an online assessment, external and the best performers in that test will then be put through a "comprehensive curriculum" that helps familiarise them with cyber-security work.

The curriculum will cover:

digital forensics

defending against web attacks

cryptography

programming

ethics of hacking

It mixes online challenges with face-to-face learning, role-playing and real-world technical challenges, said James Lyne, head of research and development at the Sans Institute, who helped draw up the programme. Extracurricular clubs will also be set up as part of the project that will be run by mentors who help participants take the skills they learn further.

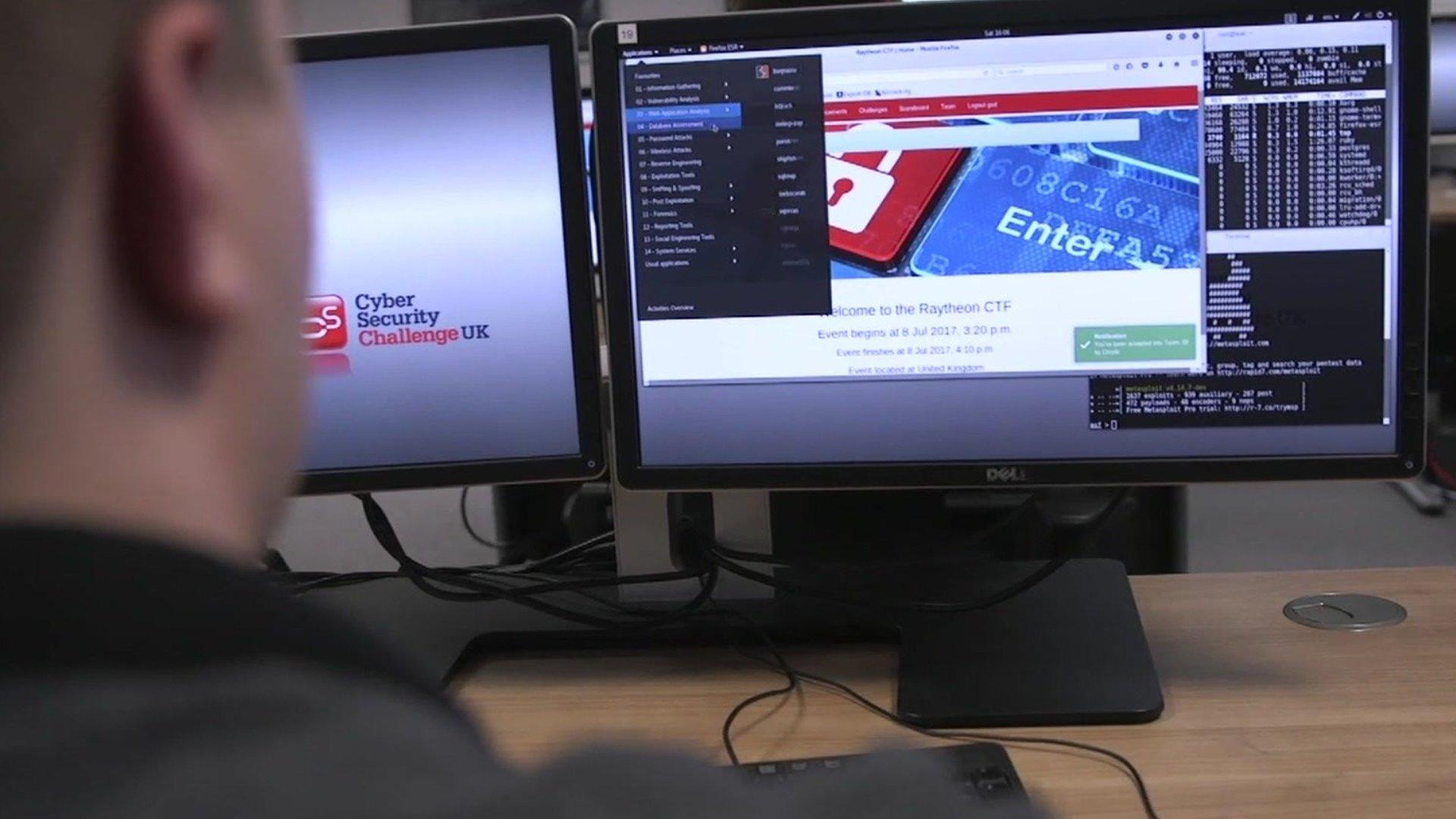

Work needs to be done to remove the stigma from hackers, say experts

It is one of several UK initiatives aimed at galvanising interest in security work among young people.

The organisation behind the Cyber Security Challenge, which runs lots of programmes seeking adult security workers, has one that is specifically aimed at schools. Called the Cyber Games, it is a series of competitions held around the UK that puts pupils through a variety of cyber-themed challenges and activities.

Another developed by Qufaro, a cyber-training college at Bletchley Park, is an add-on to the existing ICT curriculum that is centred on computer security.

Budgie Dhanda, head of Qufaro, said the lessons and projects it has drawn up form an Extended Project Qualification (EPQ) that pupils can study alongside their A/S levels. EPQs are available in many subjects, said Mr Dhanda, and let pupils explore a subject in greater detail than they would in the classroom.

"There are a lot of different modules in it that cover the spectrum of cyber-functions and capabilities the industry requires," he said.

Professional services firm Deloitte has pledged to pay the fees of any students who take on the cyber EPQ in 2017-18.

Phil Everson, head of cyber-risk at Deloitte, said it had decided to back Qufaro entrants in a bid to help plug the skills gap.

"There's already significant global demand for cyber-talent across the world," he said. "And there are not enough skilled people to meet that demand."

One industry estimate suggests there will be more than 3 million unfilled jobs in the cyber-security, external industry by 2021.

"We want to try to give the younger generation who have grown up with the internet an awareness of security and its implications," he said. "The course is about foundational skills and abilities."

The UK's National Crime Agency has sought to divert young cyber-offenders into security jobs

Deep pool

Filling the growing skills gap in the cyber-security industry needed a three-pronged approach, said industry veteran Ian Glover who heads the Crest organisation, external that certifies people who carry out security work.

More could be done to tap into the "latent pool" of technical expertise among people who already work with computers, he said, but currently handle lower-level administrative functions rather than coding or forensics.

"There are a lot of people who have 50% of the core skills they would need to work in cyber-security," he said. "Short conversion courses could quickly help them add to their skill set and swap that admin job for one on a security team," said Mr Glover.

In addition, he said, there were plenty of other graduates that could quickly put expertise in other areas, such as international studies, to use in roles such as threat intelligence.

The final, and most long-term element involved getting school pupils interested in the field, he said, but it had to be sure to give them a rounded view of the industry.

"If you can get them interested in technology that's great," he said, "but you need to be able to describe the range of roles there are in cyber-security and the benefits of being in the industry because it's an awesome place to be."

Just as important, he said, was changing the negative associations with the word "hacker".

"The perception is there that hacking is bad," he said. "We need to change the language around it and provide guidance to young people to articulate what is meant by a job or career in this space."

- Published7 November 2017

- Published9 October 2017

- Published25 July 2017

- Published25 July 2017