Drones scatter mosquitoes to fight diseases

- Published

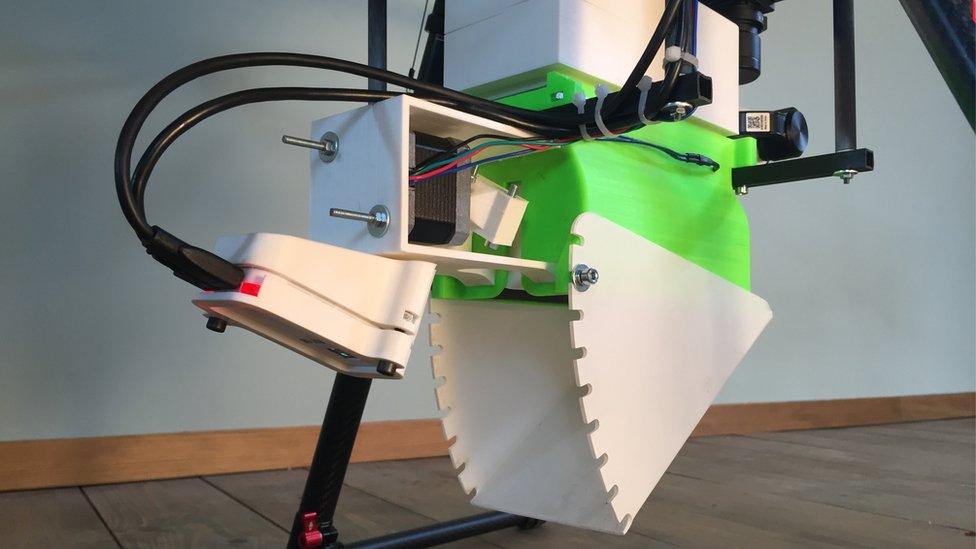

The drones can carry hundreds of thousands of mosquitoes

Drones that scatter swarms of sterile mosquitoes over wide areas are being developed to help stop the spread of diseases such as malaria.

Sterile male mosquitoes cannot produce offspring when they mate with females. By crowding out other males, they reduce the mosquito population.

But spreading them is difficult in areas without roads, so technology organisation WeRobotics has been developing drones to do the job.

It will trial the idea in 2018.

"Mosquitoes carry many diseases such as malaria, dengue fever and Zika virus. It makes them one of the biggest animal killers worldwide," Adam Klaptocz, WeRobotics co-founder, told the BBC.

Female mosquitoes bite humans

"There are lots of methods to control mosquito populations - fumigation, insecticide - but they all have downsides. Insecticide is not good for environment and needs to be constantly deployed."

Releasing sterile insects had been an effective method of population control for a variety of species, he said.

Often the sterile insects are released from backpacks carried by the scientists, but it is difficult to spread them over a wide area - and they cannot simply be dumped in one location.

WeRobotics was approached by international aid organisations to help produce a solution.

Fumigation can be expensive

Mosquitoes are exposed to radiation in a lab, which makes the infertile

"A lot of the places where these diseases exist are also places where roads do not exist. The drones could spread the mosquitoes where there are no roads," said Mr Klaptocz.

But one of the challenges is packing hundreds of thousands of fragile mosquitoes into a payload without damaging their thin legs and wings.

"A mosquito that comes out of a drone damaged - or dead - is not going to mate with females," said Mr Klaptocz.

To protect the insects, they are first cooled to 4-8C, putting them into a sleep-like state that stops them moving around.

The next challenge is releasing the insects gradually over a wide area, without waking the whole lot up at once.

To do so, the team has designed a rotating platform with holes in, through which individual mosquitoes fall. They land in a holding chamber where they wake up, and can fly out into the wild.

The green "dosing mechanism" releases a few mosquitoes at a time

"Community engagement is also a key part of the release campaign," Mr Klaptocz told the BBC.

"We may be spreading mosquitoes in areas where they are seen as a vector of death. We need to speak to the local population before a single mosquito is released."

The drones are still in development, but the non-profit company hopes to trial its technology in Latin America in 2018.

Mr Klaptocz hopes to focus on areas at risk from Zika virus first.