Tech Tent considers all sides of the AI debate

- Published

Experts have warned that "lethal autonomous" technology could be hacked

In 2017 AI was everywhere, so in the last edition of Tech Tent for this year we set off to explore artificial intelligence. What is it, where is it making rapid progress, and what are the dangers for society if we get it wrong?

What is it?

For all the excitement about the supposedly rapid advance in creating intelligent machines, there are now plenty of dissident voices arguing that AI is overhyped. After Prince Harry's interview with DeepMind's founder Demis Hassabis on the Today Programme this week, one academic tweeted this to me:

"The most rapid 'progress' in so-called AI has been by downgrading what is considered AI so that any old algorithm or machine learning is said to be "intelligent". Great PR for AI companies, rubbish science."

Stream the latest Tech Tent episode on the BBC website

Download, external the latest episode as a podcast

Listen to previous episodes on the BBC website

Listen live every Friday at 14.00 GMT on the BBC World Service

Is that really fair? Our two special guests think wonderful things are happening in this field but agree that there is a problem in defining AI. "Everyone has a different definition and it's been constantly changing since the 1960s," says Tabitha Goldstaub, co-founder of the AI consultancy Cognitio

She says computers have made great progress in some aspects of human intelligence, learning by experience in the same way a child does, to excel in tasks such as being able to distinguish between different human faces. But they then struggle with more arbitrary questions - AI is very good at doing a defined task better than a human but still isn't able to understand the logic that a baby can."

Azeem Azhar, whose Exponential View newsletter gives a weekly overview of AI developments, agrees that computers have been pretty simplistic so far doing one thing very well. He says we are now moving on to getting them to pursue "more complex goals in more complex environments."

What strikes me is that we keep moving the goalposts. Thirty years ago we would have considered a machine that could instantly translate from one language to another, like the Babelfish in The Hitchhikers Guide to The Galaxy, as a miracle of artificial intelligence.

Now we look at something like Google's instant translation Pixelbuds and complain that they sometimes get things wrong - or we ask why DeepMind's AlphaGo program cannot do the washing up.

Stephen Hawking has warned about the dangers of artificial intelligence.

AI in Health and Motoring

Making us more healthy, and changing the way we drive - or are driven - are two areas area where AI appears to have the potential to make a big difference.

In health there has been a lot of talk and little action so far. But Jerome Pesenti, who led IBM's Watson AI division and is now chief executive of healthcare firm Benevolent AI, is confident that we are on the verge of a revolution.

He explains how his firm is using AI to accelerate the process of drug discovery. The idea is that the machine now searches through the literature and the patents and comes up with a list of potential ideas for new drugs - and then the humans sift through them to decide which ones to pursue.

He says this makes the whole process much speedier: "Coming up with new ideas is tedious and serendipitous - a machine comes up with a list much faster."

The idea that the very human quality of serendipity is best removed from science might raise a few eyebrows, but Dr Pesenti also emphasises that the machine is better at making difficult decisions later, when some drugs have to be dropped: "Scientists become emotionally attached to ideas and keep on trying to push them through."

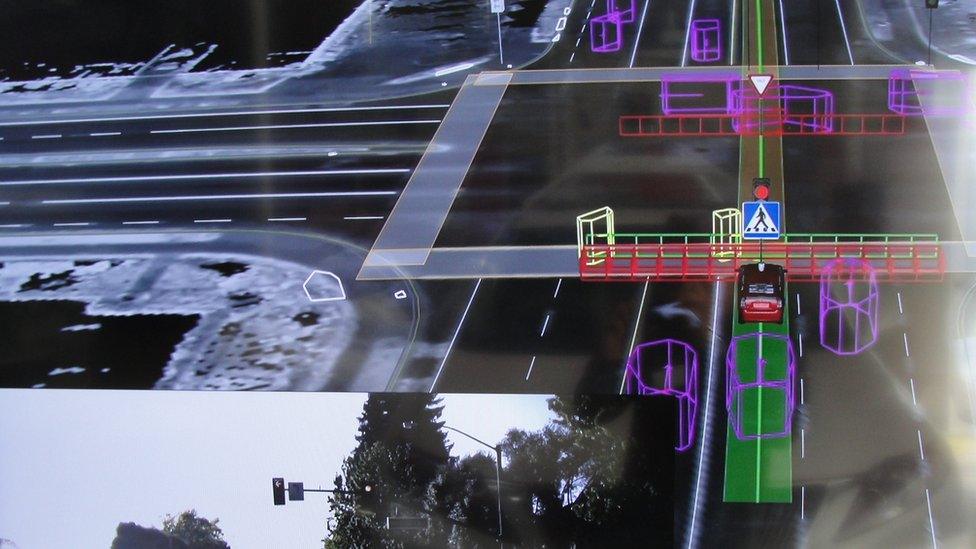

A researcher in the field of autonomous driving tells us that progress depends on combining machine learning with the infinite variety of human reactions and emotions. Chris Hoyle is technical director at rFpro, building the simulation software which is now vital in training autonomous vehicles.

Smart software and sensors combine to help robot cars navigate

But he says a synthetic world can be too perfect so that an AI trained on a straight road disappearing into the distance can end up driving up a pine tree because it interprets it as another road. "Nothing is ever straight or perfect in the real world," he says.

AI may already have surpassed humans in image and speech recognition but he says it is still not much use at predicting what comes next in a fast changing environment. "Humans are good at hearing a siren behind them and knowing they'll have to pull over to let an ambulance pass," he explains. Another example is the way motorists negotiate through subtle gestures and body language on a narrow road when there is only room for one car to pass at a time.

While he believes we are making extraordinary progress towards full autonomy, he is far more cautious than many in the motor industry in setting a date for driverless cars to take to the road. 2027 is Chris Hoyle's best bet - in the UK the government recently set 2021 as a target.

The Ethical Question

However rapid the progress in AI in health, autonomous driving or just about any area, one issue could slow things up - winning public trust in the technology.

A few years ago it was the warnings from Professor Stephen Hawking and others that AI could end up doing away with humanity which captured the headlines.

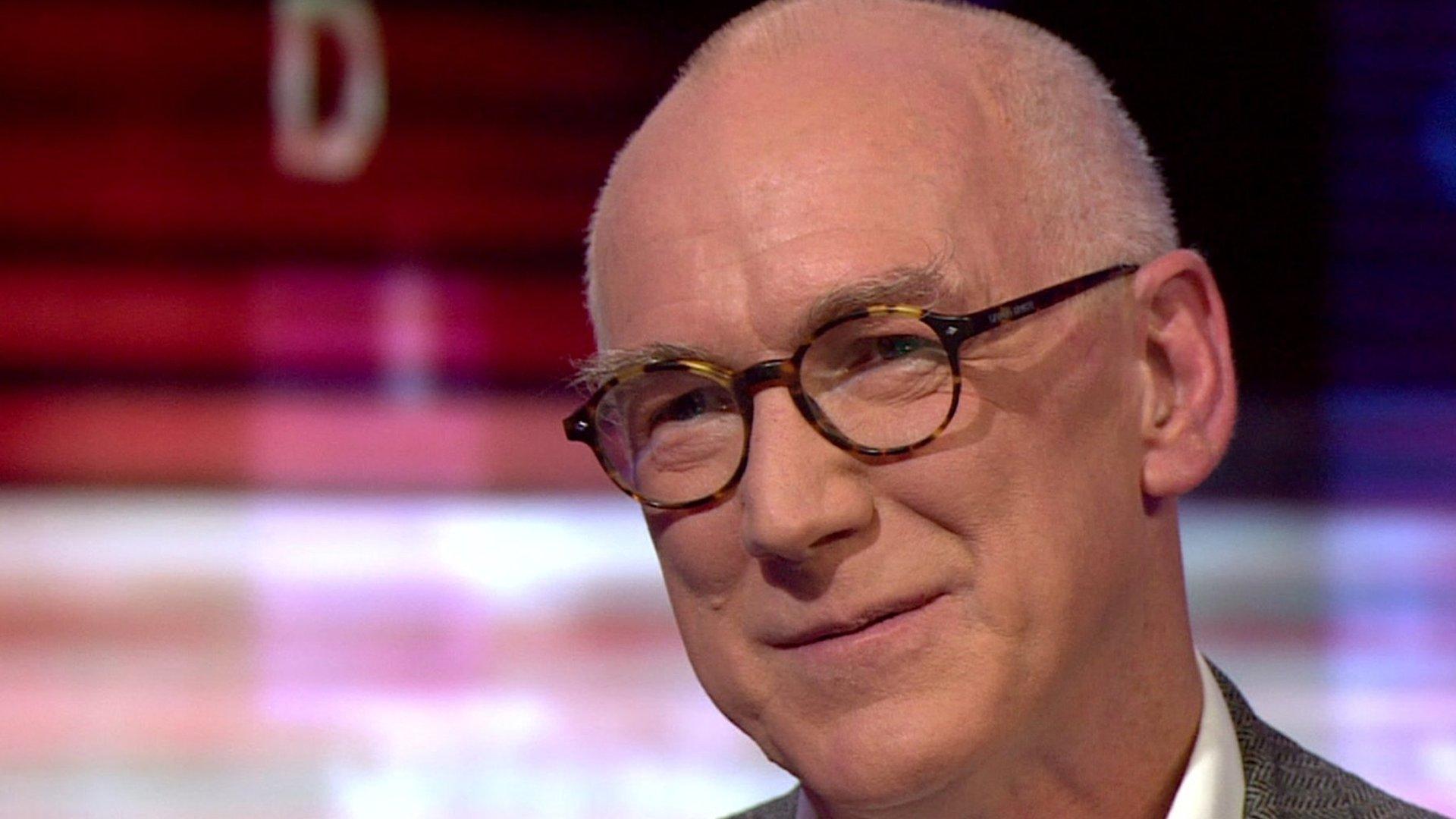

Professor Luciano Floridi of the Oxford Internet Institute tells us we need to distinguish between what's possible and what's plausible - he says it's possible but not plausible that we could win the lottery every time we buy a ticket and the same applies to the existential threat from AI. "It's a distraction and we shouldn't waste our time on it."

Both he and the internet entrepreneur Martha Lane Fox agree that there are far more pressing concerns. She points out that public trust in technology firms is already low and fears the complexity of AI could damage it further: "You won't see the machines doing clever bits of learning. It'll just miraculously happen that when you're on the internet they'll know more about you, they'll suggest things to you, they might even bias things towards you, they might be biasing things wrongly to you."

The potential for bias in algorithms which will invisibly deliver all sorts of services to us might seem just a theoretical concern - but Martha Lane Fox, who is now a director of Twitter, says automation is already having some worrying effects. Fake news is one example: "Nobody expected bots to be used to spread all sorts of nonsense content that would start to undermine democracy."

AI, with all its potential to transform society in good and bad ways, will continue to be a big story in 2018. Keep tuned to Tech Tent, where we will keep you up to date with all the latest developments.

Many are worried about the ethics of using robots in the home and workplace

- Published31 October 2017

- Published25 August 2017

- Published20 October 2016

- Published25 July 2017