Meltdown and Spectre: How chip hacks work

- Published

Watch: Chip hacks explained

As technology companies race to fix two major vulnerabilities found in computer chips, the ways in which those chips could theoretically be targeted by hackers are becoming clear.

Collectively, Meltdown and Spectre affect billions of systems around the world - from desktop PCs to smartphones.

So why are so many different devices vulnerable - and what is being done to fix things?

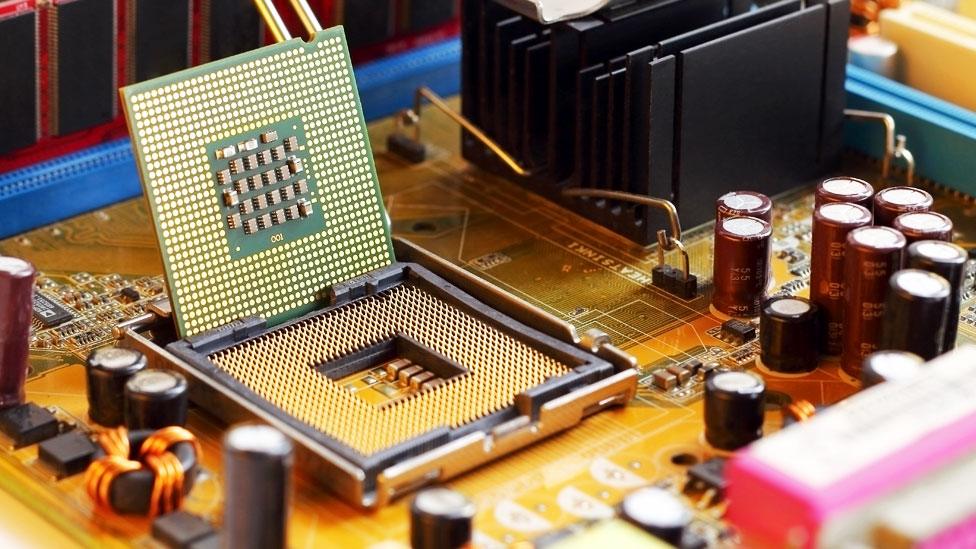

What part of my computer is at risk?

When it is working, a computer shuffles around huge amounts of data as it responds to clicks, commands and key presses.

The core part of a computer's operating system, the kernel, handles this data co-ordination job.

The kernel moves data between different sorts of memory on the chip and elsewhere in the computer.

Computers are engaged in a constant battle to make sure the data you want is in the fastest memory possible at the time you need it.

When data is in the processor's own memory - the cache - it is managed by the processor but it is at this point that the newly revealed vulnerabilities come into effect.

Spectre essentially gets programs to perform unnecessary operations - this leaks data that should stay confidential.

Meltdown also grabs information - but it simply snoops on memory used by the kernel in a way that would not normally be possible.

Some of the affected chips are used in laptops, tablets and smartphones

Both attacks exploit something called "speculative execution", which prepares the results of a set of instructions to a chip before they may be needed.

Those results are placed in one of the fastest bits of memory on the computer's processor chip.

Unfortunately, it turns out that it is possible to manipulate this forward-looking system (for example by getting the processor to perform extra operations it wouldn't normally do).

Bit by bit, this technique can allow an attacker to retrieve bits of sensitive data from the computer's memory.

How would a hacker target my machine?

An attacker would have to be able to put some code on to a user's computer in order to try to exploit either Meltdown or Spectre.

This could be done in a variety of ways, but one - running such code in a web browser - is already being closed off, external by companies such as Google and Mozilla.

Users can also, for example, use Chrome's "site isolation" feature, external to further protect themselves.

Some cyber-security experts have recommended blocking ads, external, browser scripts and page trackers as well.

Even if an attacker did get access, they would get only "snippets" of data from the processor that could eventually be pieced together to reveal passwords or encryption keys, says cyber-security expert Alan Woodward, at the University of Surrey.

That means the incentive to use Meltdown or Spectre will at first probably be limited to those prepared to plan and carry out more complex attacks, rather than everyday cyber-criminals.

Am I more at risk if I use cloud services?

Individuals are probably not at risk when they use cloud services, but the companies providing them are scrambling to work out all the implications Spectre and Meltdown have for them.

This is because of the way they organise cloud services.

Typically, they let lots of customers use the same servers and sophisticated software, "hypervisors", to keep data from different customers separate.

The two bugs imply that getting access to one cloud customer might mean that attackers can get at data from the others using the same central processing unit (CPU) on that server.

Many cloud services already run security software that looks out for these kinds of data pollution and sharing problems and these will now have to be improved to look out for these novel attacks.

Most of the affected chips have been made by Intel, it appears

Will my computer's performance be affected if I install a patch?

The patches for Meltdown involve getting the processor to repeatedly access information from memory - extra effort on its part that would not normally be necessary.

Doing this basically makes the processor work harder and some have estimated that performance dips of up to 30% could be observed.

Steven Murdoch, at University College London, explains that programs that rely on making many requests to the kernel will be most affected - but that is limited to specific types of program, such as those performing lots of database tasks.

Bitcoin mining, the computationally intensive procedure that confirms transactions on the virtual currency's network, may not be badly affected, he points out, as those processes don't involve lots of work for the kernel.

"For most people, I expect the loss of performance will not be particularly great, but it could be noticeable in some circumstances," he adds.

Are patches for both vulnerabilities available yet?

Patches for the Meltdown bug are already being released - Microsoft's Windows 10 patch comes out on Thursday, with updates for Windows 7 and 8 to follow in the next few days.

The latest version of Apple's macOS, 10.13.2, is patched, but earlier versions will need to be updated.

Patching Spectre is going to be harder because the weaknesses it exploits are used so widely on modern machines.

Processors try to break requests into multiple tasks they can deal with separately to gain any amount of speed improvement where they can, even on a small scale.

Many of the ways they do this look like they can be monitored via Spectre to gain information about what the chip is up to.

Patching this directly - essentially changing the way these chunks of silicon work - probably won't be attempted initially, but altering the way that other bits of software on computers work to prevent exploitation of Spectre should help limit the risk to users.

More worryingly, the researchers who found the bug said the "practicality" of producing fixes for existing processors was "unknown".

Forbes is maintaining an up-to-date list, external of the technology companies' patches and responses to Meltdown and Spectre.

- Published4 January 2018

- Published4 January 2018