Exposed Amazon cloud storage clients get tip-off alerts

- Published

Classified Pentagon data was left exposed for years on a publicly accessible server

Security researchers have posted "friendly warnings" to users of Amazon's cloud data storage service whose private content has been made public, the BBC has learned.

The BBC found almost 50 warnings posted to the firm's servers. Many had more than one warning uploaded to them.

The messages urged owners to secure their information before it was stolen by malicious hackers.

There was a rash of data breaches involving Amazon Web Services in 2017.

Misconfigured settings by users were repeatedly blamed.

Although Amazon is best known for its online shopping service, its AWS division serves many of the world's biggest businesses as well as governments and other public bodies.

Varied alerts

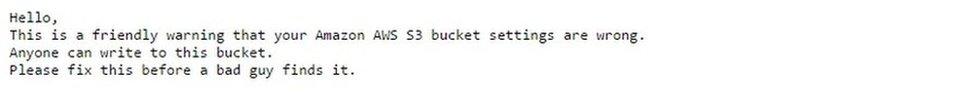

The messages discovered on the US firm's data stores varied.

Some just told the owners that their settings exposed data and others were more explicit in their warnings about what could happen.

One said: "Please fix this before a bad guys finds it."

The BBC passed its list of sites that had received warning messages to Amazon as week ago, so it could contact the customers and suggest they review their settings.

What is cloud storage?

In essence, these machines act like the hard drive on your desktop computer and can hold almost any type of data or file.

Organisations use these cloud-based stores for all kinds of tasks. Some use them to hold images, documents and other files that populate their websites. Others use them as repositories for detailed data that is mined or analysed to help other bits of their business.

They are also popular because sometimes they can be set up using only a credit card - much more quickly than would be possible via a company's internal admin systems.

Lost buckets

Security researcher Robbie Wiggins, who regularly seeks out insecure cloud systems, said he had received a range of reactions when telling an organisation that their data was wide open.

"I've had a few responses ranging from monetary rewards to thanks," he told the BBC. "I've struggled with a good few, especially the government for Argentina."

Often companies made it difficult to report problems because no contact details were available for security teams or server administrators.

Mr Wiggins said he currently had a list of about 2,000 insecure data stores, also known as buckets, about which he was steadily informing affected organisations.

"Lots of buckets appear to been abandoned and forgotten about," said Mr Wiggins.

The main target of the security experts scanning for mistakes are servers supporting Amazon's Simple Storage Service (S3) - part of its AWS business.

Data on millions of WWE fans was lost via a wrongly configured cloud server

Over the last 18 months, Uber, Verizon, Alteryx, the WWE, US defence contractor Booz Allen Hamilton, Dow Jones and three data mining companies have exposed data via misconfigured S3 buckets. Between them the firms lost data covering the digital identities of hundreds of millions of people.

Robin Wood, who wrote a bucket-scanning tool that many researchers use, said the ease with which the storage can be bought and configured made them very attractive to a lot of companies.

They were particularly useful for short-term projects that had to be set up and run quickly.

Often, said Mr Wood, the buckets set up for a particular short-term project were mothballed once the venture was finished. As time went by the software on these abandoned sites became easier to successfully attack because it was no longer updated with patches for known bugs.

The warnings urge cloud account owners to tighten up their settings

"It's amazing how many larger firms have a website or web hosting package that the security and IT teams know nothing about," he told the BBC.

Other stores were left open to get around configuration problems that can crop up when several different firms work on the same project, he said.

"What tends to happen is that if something is not working properly they will open it up a bit to see if that fixes it," said Mr Wood. "They just keep clicking until it works."

Anyone coming across the data might be able to scoop up valuable information, such as database files and login data, that could help them gain access to other networks of the same company, he said.

Scanning for vulnerable buckets was straightforward because of the way Amazon organised its service, he added.

Nasa has used the S3 service to share data it has gathered from satellites and telescopes

Basic service

A spokeswoman for Amazon said the default configuration settings on its S3 service kept data private. She said it had created several tools, external to make it easier for S3 customers to secure data or work out who could access it.

For instance, she said, the main management screen that customers use to manage buckets used a "traffic light" system to show which were open to public view and which were more tightly controlled.

And, she added, just because buckets were public did not mean they were wrongly configured. Many large organisations, such as Nasa and the Open Street Map project, made huge amounts of information available to spur collaboration, she said.

Despite this help many firms still got cloud security wrong, said James Hatch, director of applied intelligence at BAE Cyber Services.

This was partly because firms did not appreciate what they were buying when they signed up for an online data storage service such as S3.

Many people regarded cloud services as being akin to a hotel, in that they relied on the organisation to provide the working infrastructure that they then used, he told the BBC.

Instead, he said, the service they got was much more basic.

"When you are using pure infrastructure cloud services it's one step away from that. The starting point is more like an empty plot of land," said Mr Hatch. "They might give you the right building blocks to get the security right, but it's up to you to do it."

- Published14 February 2018

- Published29 November 2017

- Published11 February 2018

- Published28 February 2017