UN: Facebook has turned into a beast in Myanmar

- Published

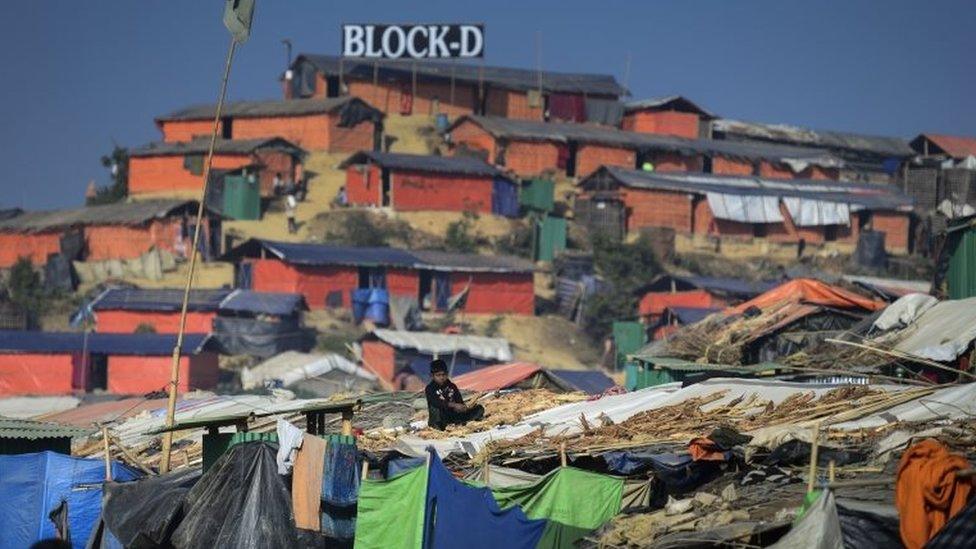

Hundreds of thousands of Rohingya refugees have fled to Bangladesh

UN investigators have said the use of Facebook played a "determining role" in stirring up hatred against Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar.

One of the team probing allegations of genocide in Myanmar , externalsaid Facebook had "turned into a beast."

About 700,000 Rohingya have fled to Bangladesh since Myanmar's military launched an operation in August against "insurgents" in Rakhine state.

Facebook has said there is "no place for hate speech" on its platform.

"We take this incredibly seriously and have worked with experts in Myanmar for several years to develop safety resources and counter-speech campaigns," a Facebook spokeswoman told the BBC.

"This work includes a dedicated Safety Page for Myanmar, external, a locally illustrated version of our Community Standards, and regular training sessions for civil society and local community groups across the country.

"Of course, there is always more we can do and we will continue to work with local experts to help keep our community safe."

'Incitement to violence'

The UN's Fact-finding Mission on Myanmar announced the interim findings of its investigation on Monday.

During a press conference the chairman of the mission, Marzuki Darusman, said that social media had "substantively contributed to the level of acrimony" amongst the wider public, against Rohingya Muslims.

"Hate speech is certainly, of course, a part of that," he added.

"As far as the Myanmar situation is concerned, social media is Facebook and Facebook is social media."

A colleague acknowledged that the service had helped people in the country communicate with each other.

Yanghee Lee said that Facebook had "turned into a beast"

But Yanghee Lee, Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, added: "We know that the ultra-nationalist Buddhists have their own Facebooks and are really inciting a lot of violence and a lot of hatred against the Rohingya or other ethnic minorities.

"I'm afraid that Facebook has now turned into a beast, and not what it originally intended."

The interim report is based on more than 600 interviews with human rights abuse victims and witnesses, which were carried out in Bangladesh, Malaysia and Thailand.

In addition the team has analysed satellite imagery, photographs and video footage taken within Myanmar.

This photo, taken in October 2017, shows burnt villages in Northern Rakhine State

"People died from gunshot wounds, often due to indiscriminate shooting at fleeing villagers," the report said.

"Some were burned alive in their homes - often the elderly, disabled and young children. Others were hacked to death."

The government of Myanmar has previously said the UN needs to provide "clear evidence" to support allegations of crimes against Rohingya.

Officials have claimed that "clearance operations" against militants responsible for attacks on police stations ended in September, but that has been disputed.

Refugees and human rights organisations, including Amnesty International, have accused the military, external of carrying out executions, rapes and the burning and bulldozing of hundreds of villages.

The UN has said that the government has attempted to block its efforts to carry out an independent investigation.

Facebook has previously discussed the problems it has faced trying to tackle hate speech in the country.

Last July, it gave the example of policing use, external of the word "kalar", which it said could be used both innocuously and as a slur against Muslims.

"We looked at the way the word's use was evolving, and decided our policy should be to remove it as hate speech when used to attack a person or group, but not in the other harmless use cases," it explained.

"We've had trouble enforcing this policy correctly recently, mainly due to the challenges of understanding the context; after further examination, we've been able to get it right. But we expect this to be a long-term challenge."

A final report from the UN team is due to be published in September.

- Published12 March 2018