Facebook data - as scandalous as MPs’ expenses?

- Published

Data about Facebook users is gathered and shared all the time say industry experts

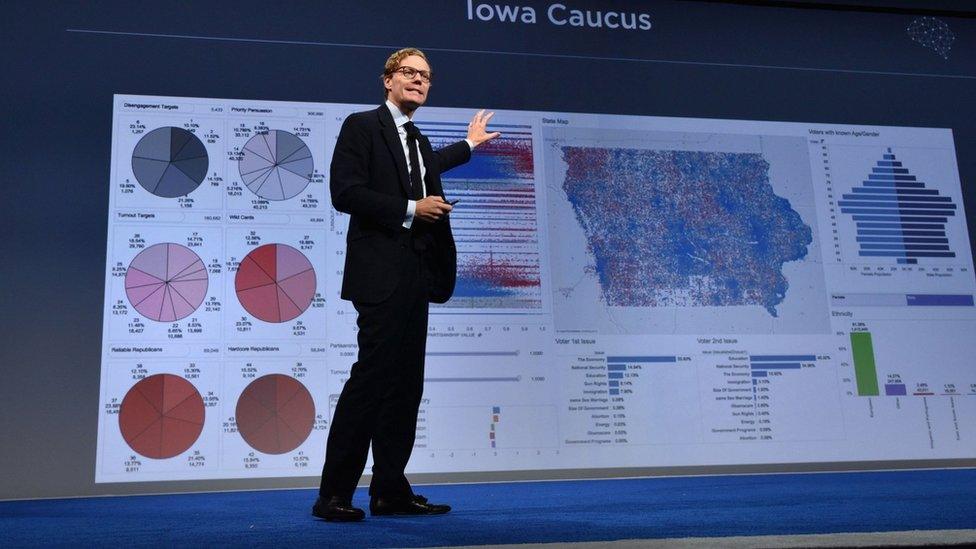

The gathering storm over how millions of Facebook profiles were apparently exploited for political purposes raises all sorts of questions about how our data is used.

But already some in the data and marketing industries are pouring cold water on the story which the Guardian's Carole Cadwalladr, external has pursued with such admirable vigour.

"Nothing very new here," they say with a world-weary sigh. "This sort of thing has been going on for years." But that surely is the point - we are finally waking up to a murky world where there is little regulation, and companies can trade our personal information without a care.

Some in the data industry agree. "It's a bit like the MPs expenses scandal," says Nick Halstead, an entrepreneur who has started several data analytics businesses. He believes, that just as MPs had a rude awakening when they were caught out doing what was accepted practice for years, so data firms and the social media giants will have to change their ways.

He says the method used by an academic who ran a personality quiz to gather Facebook data and then allegedly passed it to Cambridge Analytica is a familiar one: "I can name you 10 companies that have hundreds of millions of Facebook profiles using similar methods."

He says these firms are not doing anything illegal, and although they should not be passing on the data to others, they often do.

Mr Halstead thinks a recent change in Facebook's rules for external developers which made it harder for them to simply scrape data from users' public profiles, may be a sign that the company knows there is a problem.

It might have another as the public row over the data has hit Facebook shares which were down about 5% as politicians, pundits and regulators queued to demand more information.

Privacy please

For Stephanie Hare, a tech expert who has worked in the data field, the Cambridge Analytica story raises big questions over a lack of accountability: "What is really striking here is the absence of any oversight."

Nobody, she points out - not the social network, nor the data company or the academic researcher - seems to have thought that it was their job to ask if data had been improperly shared, and if so to ensure it was deleted.

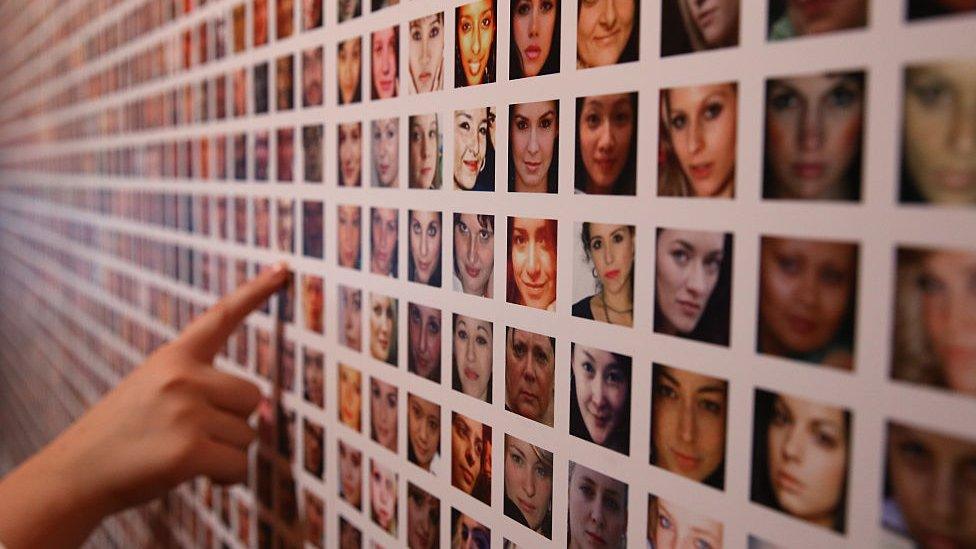

Questions are being asked about how profile data was gathered

She thinks there is going to need to be some kind of regulatory oversight to make sure the rules are followed.

Much has been made of the fact that users who sign up to the kind of personality quiz used in this case have to explicitly give permission for their data to be accessed. But Stephanie Hare says it is unfair to put the burden on people with busy lives to read through the fine print. And she feels that Facebook's settings should be set to maximise privacy by default.

"It's our jobs as technologists to design systems that are safe," she says. "I don't get on an aeroplane as a passenger and make my own safety checks."

I spent this morning giving a talk at a school in South Wales about the power of social media platforms to spread fake news. I took some time to explain just how much power Facebook puts in the hands of advertisers - and political parties - to target their messages very precisely at, say, 15-25 year olds in Pontypridd who like motor racing.

My audience, all keen users of social media, seemed surprised to learn that Facebook owned Instagram and WhatsApp, and Google owned YouTube, meaning that just two giant companies could exert huge influence over the information they received and how they thought.

I also warned them against signing up to quizzes on Facebook and elsewhere. But we are now asking a lot of this generation, demanding that they examine every news story to be certain of its sources, and making them read through arcane privacy statements everywhere they go online.

Perhaps it is time for the grownups to give them an online world which is safer by default.

- Published19 March 2018

- Published18 March 2018

- Published17 March 2018