FBI sought Google location data of many to catch robber

- Published

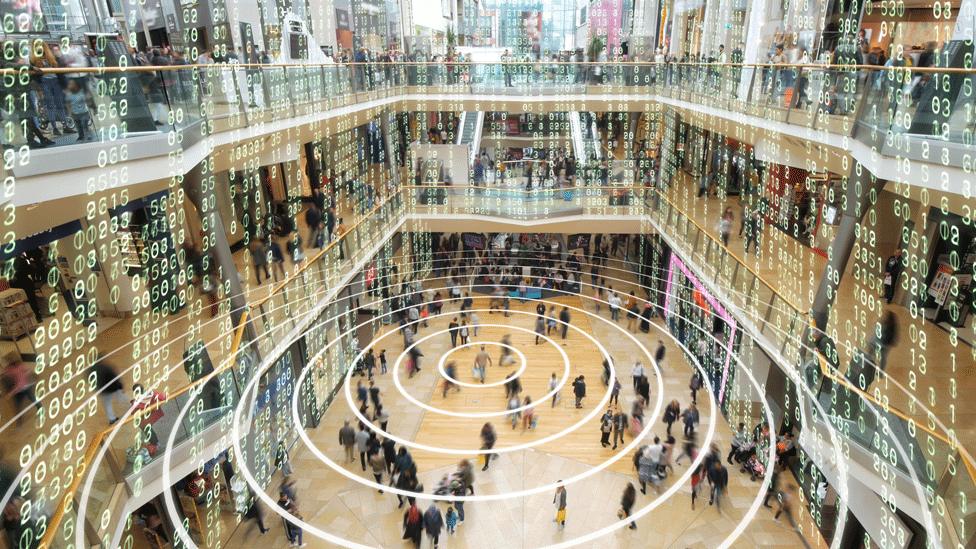

Google is under fire for keeping location data when users have switched off the function

The FBI requested location data from Google covering 100 acres (0.4 sq km) as part of an investigation into a series of robberies in US city Portland, reports Forbes., external

The request for data on users in the area amounted to an "indiscriminate search", said lawyers.

It comes amid news that Google stores geographical data from phones even when location history is turned off.

But the search giant did not comply with the FBI's request.

During March and April of 2018, the police were investigating a spate of robberies of small businesses in the Portland area.

A suspect was eventually caught and this month pleaded guilty to 11 of the 14 robberies or attempted robberies.

But in the early stage of the investigation, the FBI issued a search warrant asking Google to hand over data that would identify people using its location services on a mobile device near two or more of the locations of the robberies.

It asked for:

names and full addresses

telephone numbers

records of session times and duration

date on which account was created

length of service

IP address used to register the account

log-in IP addresses associated with session times

email addresses

log files

means and source of payment, including any credit or bank account number

The document seen by Forbes, external suggests that the police were interested in only users who had been at at least two locations within specified timeframes.

Despite this, lawyer Marina Medvin told the publication it represented an "indiscriminate search of a large group of people".

Such general searches, she added, are prohibited under the US Constitution.

"Having such a broad search means that more and more innocent people - people who have not done anything wrong - were going to have their personal data swept up and turned over to the government," said Zachary Heiden, a lawyer at the American Civil Liberties Union.