Techno-nationalism could determine the 21st Century

- Published

The battle to own the future: non-democratic states are becoming more assertive and strategically effective by investing in technology

One of the most important stories in the world right now is the battle to own the future by investing in technology, in which non-democratic states are becoming more assertive, strategically effective and - unencumbered by voters' preferences - able to think in epochal rather than electoral cycles.

For the likes of China and Saudi Arabia, projecting national strength is bound up with expensive, and often pretty safe, bets on the industries of the future. This is techno-nationalism. Though we are living with its consequences already, its impact will grow exponentially.

Techno-nationalism marries two trends that are central to our current historical moment. First, the remarkable acquisition of power through data and "network effects" of just a few companies based mainly near San Francisco, and the escalating battle between these companies and Chinese rivals. And second, the decline of the post-1945 Western-led world order.

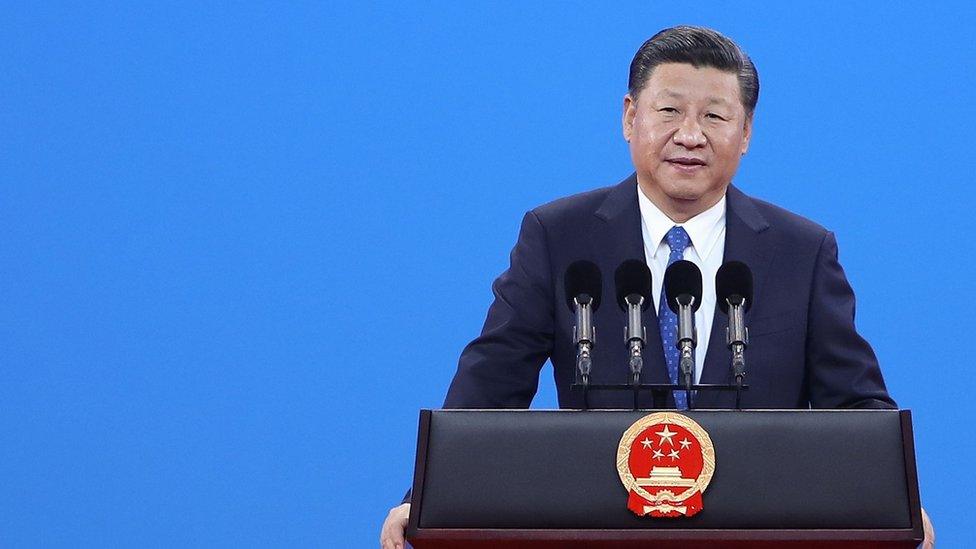

China's President Xi Jinping is focused on a massive investment programme in emerging technologies

I examined the second of these in a recent BBC Radio 4 programme, made with the brilliant Phil Tinline, external: The Decline of the West. Its argument is that every aspect of the post-1945 settlement - American leadership of a rules-based international order, upheld by key global institutions, and a convergence toward liberal democracies and open markets - has become unstable. Sheer demography, in particular the youth bulge in parts of Asia, means we have embarked on a post-Western era.

(If you're interested in where this leaves democracy, that was the subject of this edition of Start the Week on BBC Radio 4).

China's bid for respect and a leadership role in this new era has countless expressions, of which the Belt and Road Initiative is perhaps the most exhaustively reported. But its "Made in China 2025" plan is perhaps more important. This is a massive investment programme in emerging technologies.

China is aware that it lags America in some key areas, such as semi-conductors. As the excellent James Kynge, external has noted, of the $300bn committed to Made in China 2025, external, half is therefore devoted to semi-conductors. Meanwhile, global leadership in the other technological sectors thought likely to dominate this century, from the internet of things to robotics and artificial intelligence, is now an explicit aim of the Xi Jinping regime.

Last year, for the first time, China received more patent applications than the US, the EU, Japan and South Korea combined. Also last year, Chinese companies including Oppo and Vivo accounted for 43% of global smartphone purchases - more than Apple in the US and Samsung in Korea.

President Trump has cited China's ambitions in technology as a justification for imposing tariffs on Chinese goods. Chinese investment in venture capital deals in early stage American technology companies is also dramatically rising, external.

There is an irony here. A generation ago, it was investment by the US government that largely created the technological era in which we live today. The internet itself came out of work done for the Department of Defense; support for companies from Intel to Apple helped their entrepreneurs create modern computing; and many of the components inside your smartphone arose from US government research.

Baidu is the lead search engine in China and the fourth most visited site in the world. It is one of the four most powerful companies in the Chinese digital economy

Today, it is China's government that is championing technological supremacy. This is the other key difference between American and Chinese approaches to technology. In the US, the best innovation, the smartest minds, and crucially the ownership of intellectual property, is in the hands of the few. That is, private companies that don't actually employ many people, but whose bosses have acquired fabulous wealth.

I have argued elsewhere that the future of commerce may look like a BAT with FAANGS, external, in which the Chinese behemoths of Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent seek to outsmart the US-based Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix and Google. The Chinese companies, which emerged in a mobile-first world, have deep relations with their government, which is capitalist but not a democracy. They depend on Xi's regime for approval and freedom.

In the US, however, government and tech are increasingly opposed. By this I don't mean President's Trump's inaccurate claims that Google and Twitter are full of left-wing bias. Rather, it is clear that regulators and lawmakers in Washington want to clip the wings of the biggest technology companies.

Techno-nationalism is not, however, merely about a new Cold Technological War between the US and China. The world today is multi-polar, not bi-polar. India's nationalist Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, has his own "Make in India" manufacturing drive. In February he gave a speech in Bombay, external outlining an Indian vision , externalof the future of tech.

But the country whose manoeuvres in tech are most intriguing is Saudi Arabia. Put aside quite what that country did or didn't say to Tesla founder Elon Musk, external about whether they would help him take his electric carmaker private, a position he has now backed down from.

The biggest technology fund in the world, the Vision Fund of Japan's SoftBank, is worth a staggering $100bn, around ten times bigger than its nearest rival. And where did its founder Masayoshi Son get $45bn of the first $100bn he raised? From Muhammad bin Salman, the Saudi Crown Prince.

Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman is planning the most technologically advanced city in the world

On top of the $2bn invested in Tesla through its Public Investment Fund, the Saudis have put $3.5bn into Uber Technologies and $1bn in Virgin Group's space companies. And in Neom,, external the $500bn metropolis the Saudis are currently building in their kingdom's northwest, bin Salman has plans for the most technologically advanced city on Earth.

The House of Saud, which is planning for a world less dependent on oil, has no plans to allow the people of their lands to vote on who governs them. Xi has strengthened his grip on the Chinese Communist Party. These authoritarians don't have to worry about seeking their people's approval in elections. They think of history in the grand sweep of epochs, and know their own intellectual heritages in science and technology are rich.

By allying their financial power and nationalist ambitions with the most consequential technologies currently being developed anywhere in the world, they are making a bet for 21st century dominance to which Western democracies currently have virtually no meaningful response. Perhaps voters should be told.

This is an edited version of an audio essay for BBC World Service.

If you're interested in issues such as these, you can follow me on Twitter, external or Facebook, external; and subscribe to The Media Show podcast, external from Radio 4.