Lucy McHugh death: The challenge of accessing Facebook data

- Published

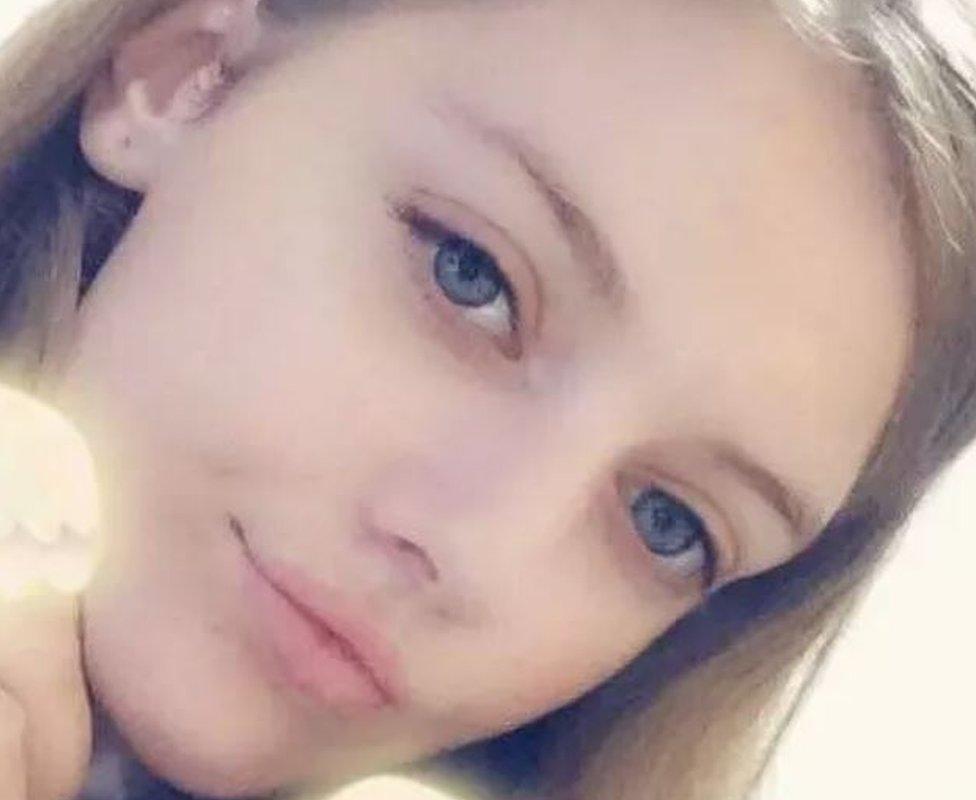

CCTV footage showed Lucy McHugh half a mile away from the Southampton sports centre where she was found stabbed to death

Police investigating the murder of 13-year-old Lucy McHugh have called for social media companies to respond to requests for information more quickly. But is this always possible - or desirable?

I spoke to a detective recently, deeply frustrated by his dealings with one social media company.

He specialises in combating child sexual exploitation online and as part of an investigation had found the profiles of a number of people - several were offenders who were grooming, abusing and blackmailing children - several more were the children themselves, victims of the grooming.

None of them used their real names - they were effectively anonymous. All he knew was that there were children at risk and offenders at liberty.

He urgently requested information about these users from the tech company - it didn't even reply to his request.

His example may be an isolated one, but it highlights the problem at the heart of this issue. How do police investigate a crime committed against a child in one country, by an offender living in another, using a platform based in a third?

Facebook is a US company and so has to abide by US laws on data protection and due process - which means they have no duty to hand any information over to a foreign police force - only a request via the US Department of Justice using something called the Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty will oblige disclosure. But this is cumbersome, expensive and can take months.

That said Facebook does have a choice in the matter - as a matter of policy it will hand over information if there's an immediate threat to life or the safety of a child. If that's the case why not in the case of a murder inquiry?

Last week, Stephen Nicholson, a suspect in the murder of Lucy McHugh, was jailed for 14 months having admitted failing to comply with an order under the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act requiring him to disclose a Facebook password.

Detectives investigating the teenager's murder said it was taking an "inordinate amount of time" to access evidence from Facebook and Met Police Commissioner Cressida Dick has called for detectives to have access to material from social media companies "within minutes".

On its part Facebook says it already has a team that works with law enforcement and it has been co-operating with Hampshire Police on the Lucy McHugh case.

A suspect in Lucy McHugh's murder has been jailed for refusing to disclose a Facebook password

But there are other issues at play. Some critics say the platform has just got too big and cannot effectively be policed. It now claims to have two billion users.

In the first six months of last year it received almost 80,000 requests from police forces around the world. That figure had risen by 20% since the year before.

But tech companies do have a very fine line to tread.

It would seem hard to object to a request made by a police officer in the UK investigating the murder of a child - but what if law enforcement in a repressive regime approaches Facebook wanting information on a blogger critical of the government?

The convoluted legal process has a purpose - acting both as sword and shield.

- Published4 September 2018

- Published31 August 2018