Climate change: Is your Netflix habit bad for the environment?

- Published

Watching your favourite show or listening to your playlist has never been easier.

A virtually endless supply of film, music and TV can be streamed and downloaded almost instantly.

But at what cost to the environment?

Vast amounts of energy are needed to keep data flowing on the internet and demand will only increase as our reliance on digital services grows.

Some of that energy is generated from clean energy sources, but much of it comes from burning carbon-based fossil fuels, which scientists believe is a contributing factor to rising global temperatures.

The latest report by climate scientists demonstrates the scale of the dangers faced from carbon emissions.

"How we power our digital infrastructure is rapidly becoming critical to whether we will be able to arrest climate change in time," says Gary Cook, IT sector analyst at Greenpeace.

So, could cutting down time spent on the internet really make a difference to energy consumption and global warming?

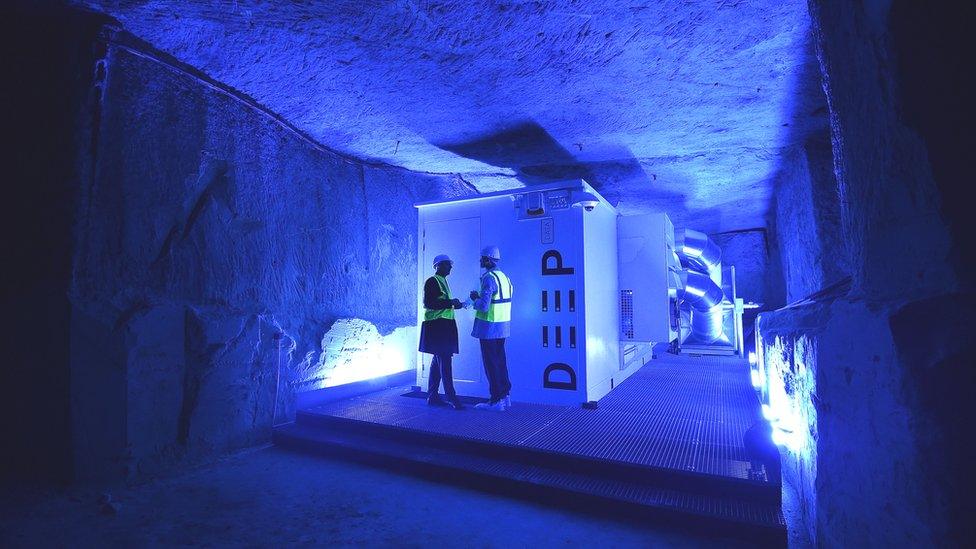

Building data centres underground can help keep servers cool

The entire information technology (IT) sector - from powering internet servers to charging smartphones - is already estimated to have the same carbon footprint as the aviation industry's fuel emissions, external.

And it is on course to consume as much as 20% of the world's electricity by 2030, according to Anders Andrae,, external who is based at Huawei Technologies.

Streaming video accounts for the biggest big chunk of the world's internet traffic.

Watching video over the internet at home is roughly the same as having two or three old-fashioned incandescent light bulbs on, say Prof Chris Preist and Dr Dan Schien, of the University of Bristol's computer science department.

As well as the power used by these devices, energy is consumed by the networks that distribute the content.

More demand for the technology also means more energy is required to store and share vast amounts of information.

This is where data centres come in - often in vast buildings that house computer servers that store, process and distribute internet traffic. The servers themselves require a great deal of cooling.

Most of the world's internet traffic goes through these data centres and they host streaming platforms such as Netflix, Facebook and YouTube.

These data centres are estimated to currently consume at least 1% of the world's electricity every year, a figure that is expected to rise in the future.

They also account for about 0.3% of global CO2 emissions.

Mr Andrae says data centres being built across the world need to be fed by renewable energy to minimise these emissions.

The European Commission-funded Eureca project found that data centres in EU countries consumed 25% more energy in 2017 compared with 2014.

The lead scientist, Rabih Bashroush, calculated that five billion downloads and streams clocked up by the song Despacito, released in 2017, consumed as much electricity as Chad, Guinea-Bissau, Somalia, Sierra Leone and the Central African Republic put together in a single year.

What can you do about it?

Every time you sit down to watch or listen to something online, the amount of energy consumed might change. It depends on a range of factors including the efficiency of the device.

Terrestrial broadcast TV is a lot more efficient than current streaming technologies for TV channels that are watched by a large number of people, say Prof Preist and Dr Schien.

Mobile phones tend to be the most energy-efficient - more so than a TV or a laptop.

It depends how you stream too. A mobile using wi-fi consumes less energy than one connected to 3G or 4G.

Even if you're not using your device, by having home wi-fi active, you're still consuming energy, says Prof Preist. "So in the home, a lot of the energy consumption comes from us all having our network equipment on 24 hours a day."

Some data centres can be more efficient than others. Keeping them in cooler locations, underground for example, can cut down on large quantities of energy required for cooling.

The International Energy Agency's (IEA) latest report suggested that despite the increased workload for data centres, which will triple by 2020, the amount of electricity used will only go up by 3%.

This is down to continued improvements in the efficiency of servers and data centre infrastructure, and a move to bigger but more efficient centres.

A data centre in Utah used by the US national security agency

Some of the large technology companies have been praised for being more open about how efficient they are.

Facebook expects its new data centre in Singapore will be powered by 100% renewable energy, something that Apple says already happens with all its global facilities., external Many other firms have committed to reaching that goal.

Companies also make up for the amount of non-renewable energy that they consume by supporting renewable energy projects.

Scrutiny of less well known and smaller companies and their energy consumption should be a priority, says Mr Bashroush.

"More attention needs to be paid to the smaller data centre facilities that are off the radar, this is where the next big opportunity to save energy is, the big players are not that bad in comparison," he says.