Was Jeff Bezos the weak link in cyber-security?

- Published

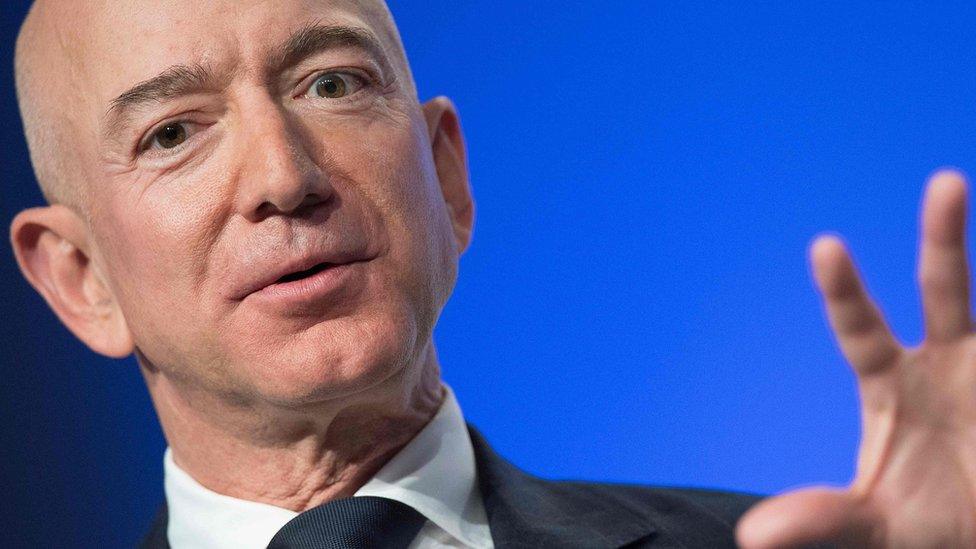

Amazon chief executive Jeff Bezos

A week ago, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos revealed what he described as an extortion attempt by the National Enquirer.

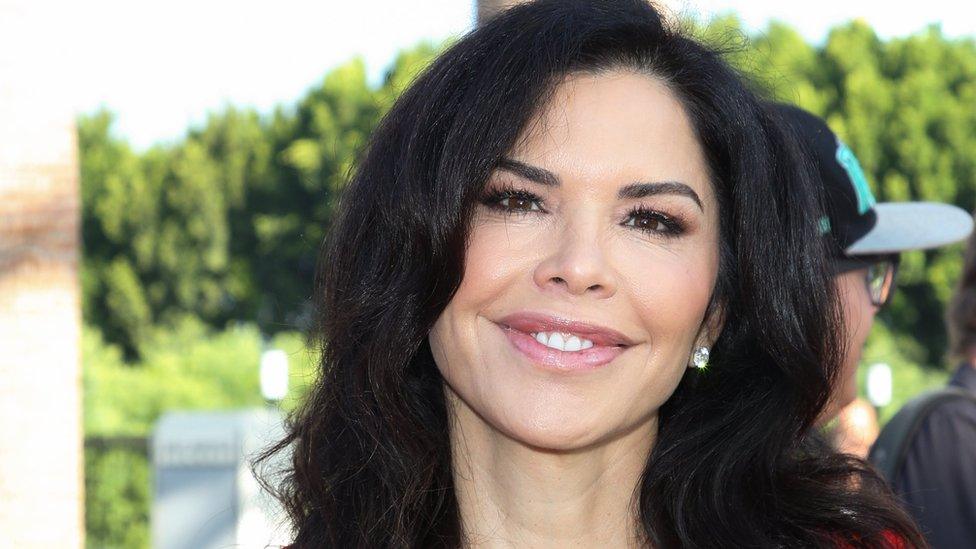

The tabloid appeared to have got hold of some very intimate texts and photos he had sent to his girlfriend Lauren Sanchez.

In my report for the BBC World Service programme The World This Week, I consider why humans are often the weakest link in cyber-security.

Mr Bezos is the world's richest man, building his fortune via a company that is transforming the way we live with innovative technology.

His business, Amazon, has cyber-security at the heart of everything it does.

So how come he risked sending highly embarrassing photos to his lover's phone only to see them hacked and end up in the hands of a tabloid newspaper?

If he could not stop himself from doing something so stupid in the first place, the argument goes, surely his company could have provided him with the world's most unhackable phone?

On Twitter, someone called counterchekist had the answer to this, saying that all the world's money and experts could not protect a device against its biggest weakness, "the human using it".

In other words, technology can only go so far. Good cyber-security depends on educating people not to be idiotic.

The suggestion that the human factor is the weakest link is probably the biggest single cliche in the cyber-security industry.

Mr Bezos sent selfies to TV host Lauren Sanchez

Security firms may sell all sorts of expensive tools to protect their customers from attacks, but all too often they are rendered useless when someone in the organisation clicks on a dodgy link or forgets to install a vital software update.

Look at any of the major cyber-security incidents of recent years and you are likely to find they begin with a human making a mistake.

The fault that took down the O2 mobile phone network in the UK for 24 hours in December 2018 was first thought to have been the result of a hacking attack.

It then emerged that someone had failed to renew a software certificate. "One of the most basic systems administration mistakes you can imagine," a waspish comment on the Computing Weekly site said.

The attack which saw hackers - presumed to be from North Korea - take over the computer system of Sony Pictures and release all sorts of embarrassing information began with emails designed to trick executives into handing over their Apple ID credentials.

And guess what? Some of those people used the very same passwords for their Sony account. Hey presto, the hackers were in.

What is known as social engineering is becoming a key weapon in the hackers' armoury. Rather than mounting some devilishly clever hi-tech attack, they pick out a key individual and work out how to target their weaknesses.

Scammed!

A while back, I spoke to a cyber-security firm that specialises in countering so-called spear-phishing, where a senior executive is targeted for an attack. They proposed a challenge to me. Some time over the next few days they would prove that they could fool me into clicking on a questionable link in an email.

Hah, I thought. Fat chance. I am very cautious about what arrives in my inbox anyway and I will be even more watchful now.

A few days later, an email popped up from Jat, the producer of my World Service radio programme Tech Tent. He messages me several times a day. It was about my Twitter account and read: "You really need to take a look at this," pointing to a link.

Of course I clicked, and found myself on a web page belonging to the cyber-security company with a message saying: "We got you".

Somehow they had spoofed my producer's email address, and so found the gap in my defences. After all, everyone trusts their producer.

This all begs the question: if protecting your vital information depends on making humans more sensible rather than using all sorts of whizzbang technology, wouldn't it be better to hire psychologists rather than cyber-security companies?

They might even be cheaper.

Of course, the truth is that plugging data leaks is a multi-faceted business.

An organisation needs to make sure its employees have secure devices, understand the corporate data protection policies, and have a modicum of common sense.

And on that last point, even billionaires can sometimes be found lacking.

The World this Week is first broadcast on the World Service at 0900 GMT on Saturday and repeated through the weekend and you can listen to it afterwards on BBC Sounds.

- Published15 February 2019