Tech Tent - Sri Lanka’s social media ban

- Published

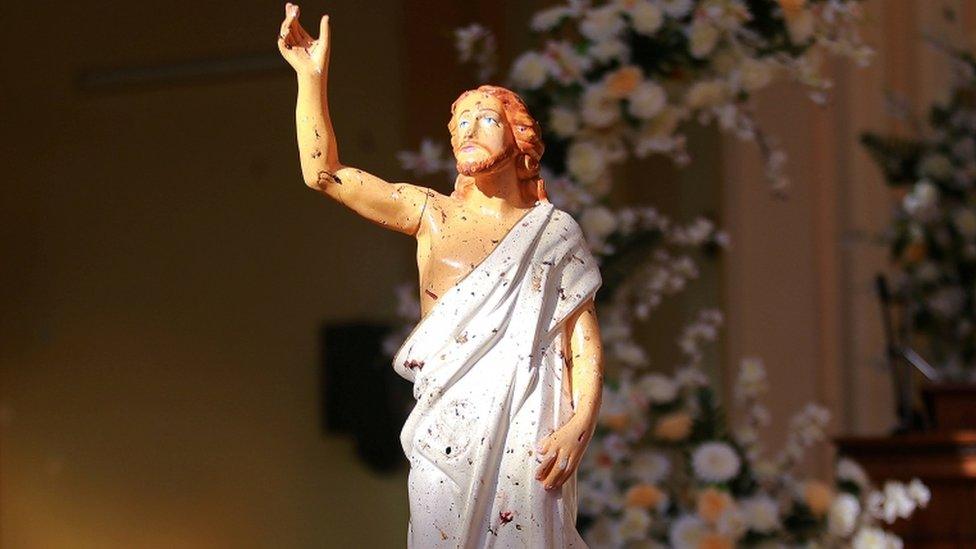

The attacks on churches left more than 250 people dead

Even a year ago a government move to block access to social media would have been greeted with a global outcry.

On Tech Tent this week we look at why the Sri Lankan government's ban has received a more muted response.

Stream the latest Tech Tent, external podcast on BBC Sounds

The move to block the likes of Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat and YouTube came in the wake of the devastating bombing attacks on Christian worshippers and tourists in Sri Lanka, which killed more than 250 people.

Previous attempts by governments to curb internet access have been seen by liberal commentators as dangerous attacks on online freedoms. But here's the headline on a New York Times column by technology journalist Kara Swisher: "Sri Lanka Shut Down Social Media. My First Thought Was 'Good'."

She said she was ashamed to admit it, but the social-media platforms' role in spreading hate and misinformation had made her welcome their temporary disappearance.

The column reflected a wider disillusionment with the idea that the web is a force for good.

During the Arab Spring, Facebook was hailed as a vital new weapon in the battle against authoritarian governments.

Now, after it was used to incite violence against the Rohingya in Myanmar and to broadcast the murderous spree of the Christchurch gunman, it is seen in a much darker light.

But from a Sri Lankan blogger and social-media activist we get a more nuanced view. "The jury is out," Sanjana Hattotuwa tells us when we ask for his views on the ban.

He created the country's first citizen-journalism site to record the failings of government and attacks on civil liberties but he accepts that many had welcomed the social-media blackout.

"I think there was an acknowledgement that what the government did would aid in the containment or the controlling of the spread of misinformation," he says.

But he believes that as time goes on, the ban could actually hinder the useful role social networks can play. "The longer the block is in place, the more debilitating it becomes for families grieving in this unprecedented time to communicate with each other.

"And also the larger public perception [is] that it is actually a means that the government uses to control or contain a growing unpopularity and public criticism of its inaction leading up to the terrorist attacks."

Mr Hattotuwa acknowledges that there is a debate to be had about the harms caused by social media but says it has become a vital means of communication in a country where the government and mainstream media are not trusted.

Last year, as anger spread over the various data and privacy scandals, the hashtag #deletefacebook trended in some Western countries.

But Mr Hattotuwa doesn't believe that will happen in his country. "That will never ever have resonance in a country like Sri Lanka, where social media is inextricably intertwined into the DNA of politics and society," he insists.

Also on this week's programme:

As the UK looks set to allow Huawei at least some role in its next-generation 5G networks we ask whether China has won a significant victory in the battle over trust in its technology firms.

And we meet Nadia Sood, whose mission is to use technology to give small businesses in India and elsewhere the capital they need to thrive.

- Published23 April 2019

- Published28 April 2019

- Published26 April 2019