The tablet computer pulled by donkey

- Published

Mobility via donkey - a simple but effective way of sharing content in remote communities

Back in 2016, mobile technology the like of which had not been seen before rolled into the remote community of Funhalouro, in Mozambique.

Pulled by donkey, the container consisted of four LCD screens, powered by solar panels.

It was a mobile roadshow, starting with music to draw a crowd and then switching to a three-minute film on the biggest of the screens.

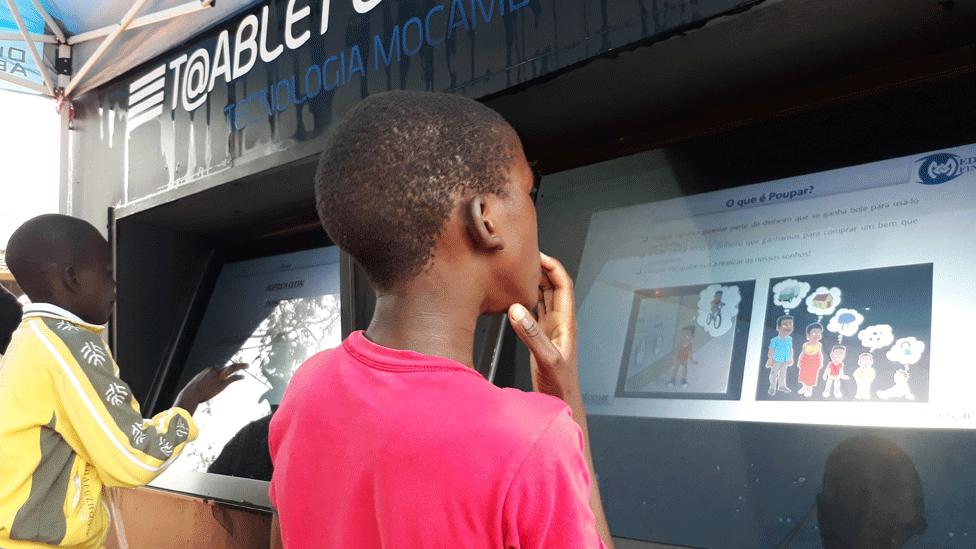

While the topic - digital literacy - was not the most entertaining, it was engaging for the audience, many of whom had never seen a screen or moving images before.

After the film, the audience was invited to use smaller touchscreen tablets to answer a series of questions about what they had seen.

There were prizes of T-shirts and caps for those with the highest scores.

For those who couldn't read, the questions were posed in diagram form.

One important element of the project is to test to see how much people have understood

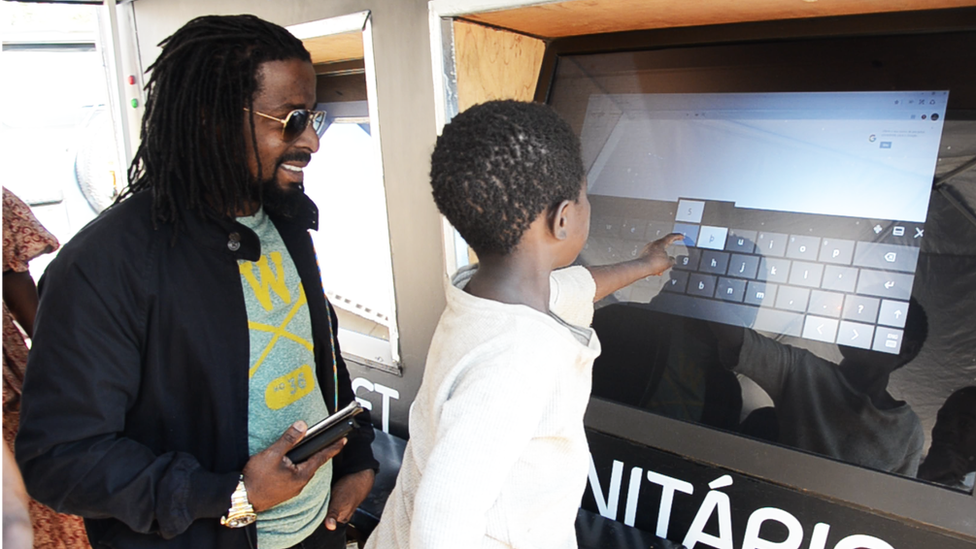

"When we arrive in a community, we try and make it a party," said Dayn Amade, founder of the Community Tablet., external

"We want to attract people and we do it with music."

Sub-Saharan Africa is projected to have 634 million mobile users by 2025, up from 250 million at the end of 2017, according to GSM Association, the trade body for mobile carriers.

Adoption of mobile technology has transformed lives, from providing people with a way to bank for the first time to helping farmers improve their crop yield.

But some countries fare better than others.

While in Kenya mobile penetration is at 91%, in Mozambique less than half of its 31 million population have mobile connections.

For some, the tablet is their first ever interaction with a screen

The project starts with music to bring the crowds

The Community Tablet aims to fill this gap and the entertainment is just the precursor to the real point of the roadshow - to educate and empower remote and rural communities on a range of topics, from public health to mobile banking to why it is important to take part in elections.

Mr Amade, who was born in Mozambique, got the idea as he watched his two young sons and saw how addicted to their tablets they were and how quickly they learned how to build things by watching YouTube tutorials.

"I said to myself that this can be used in rural communities where people aren't able to do basic things because they have never had a tutorial," he said.

Dayn Amade got the idea for a community tablet watching his own kids use their devices

There have been plenty of initiatives to increase the use of technology in countries such as Mozambique, often with patchy results.

The One Laptop Per Child initiative, for instance, aimed to transform education but failed to deliver on its promises.

Frugal innovation

"The reality of Africa means that experiments like One Laptop per child or other ways of distributing smartphones unfortunately for various reasons do not work out," said Mr Amade.

"It's impossible to give a tablet to everybody - it is too expensive and you don't know if they are going to use it or are going to sell it."

Traditionally, educational material is passed on via community theatre or cinema.

One blogger in Liberia used to painstakingly write out the news on a blackboard for those in his community without phones or access to newspapers, radio or TV.

Sometimes, the simple ideas were the best, said Ken Banks, an innovator in mobile for Africa and head of social impact at digital ID company Yoti.

"Projects like the Community Tablet are a great example of appropriate, almost frugal innovation - focusing on what works rather than what looks good," he said.

"We have the ability to solve many development problems with tools available today - but often we're too busy chasing the next shiny innovation."

Mr Amade agrees his is a very simple solution, describing it as "an adequate way of supplying digital education to people in rural communities".

"It is safe and robust. It cannot be broken and it cannot be stolen," he said.

People are tested after shows to see how much they understood and rewarded with prizes such as caps and T-shirts

The project makes money from non-government organisations (NGOs), many of which have been trying to reach remote communities via more traditional methods, such as lecturers and handing out pamphlets.

"If people get a pamphlet, they throw it away. And most people don't listen after two or three minutes," said Mr Amade.

"NGOs go to these communities to solve specific problems but the problems remain because people have not understood. With our system, people listen, interact and then we test them."

Many of the projects have seen tangible results, according to Mr Amade:

after a civic education campaign, voting increased by 45%

a family planning campaign saw a 27% increase in contraceptive intake in health centres

a financial inclusion campaign resulted in 68% more new bank accounts being opened

Mr Amade has been on the road for the past three years, visiting 90 communities in Mozambique's remotest areas.

And he has learned lessons along the way, including how to adapt the technology to account for the country's potholed and dusty roads and how to alter content to suit specific communities.

One animated video, explaining the importance of hygiene to prevent cholera, horrified one largely Muslim community because it showed someone wiping their bottom with their right hand, the same hand used to eat with.

"I've made mistakes along the way and sometimes content can offend," Mr Amade said.

Now, all content is shown to anthropologists and psychologists based at Universidade Eduardo Mondlane, a university in Maputo.

"The use of anthropologists is very refreshing and a big part of the story," said Mr Banks.

"Anthropology is ideally placed to help us understand local contexts, cultures, economics and geographies - yet many projects fail to engage them."

After viewing films, individuals are encouraged to share what they have learned with the audience

The Community Tablet has been granted a UK patent and Mr Amade is now looking to franchise it.

He hopes to expand beyond Mozambique and to make inroads into more urban communities.

Already, he is experimenting with using the system in schools to offer children careers advice.

And for those who did not have the luxury of an education, the tablet could be an incredibly powerful tool, he said.

"The reality of Mozambique is that the quality of education is extremely poor and that is why we remain poor because people are not being empowered properly," Mr Amade said.

"By explaining to people and showing them, you can solve many problems, including the poverty we live in."

- Published20 March 2019

- Published26 January 2019