The Raspberry Pi goes Fourth

- Published

Rory got his Pi 4 set up with no help from a youngster

My, hasn't it grown. It started as a modest project to get a few thousand children coding but has since become the best-selling computer ever made in the UK.

It is used by schools, hobbyists and in factories - and even turns up as a means of hacking Nasa. And on Monday, seven years after the first one went on sale, Raspberry Pi 4 is launched.

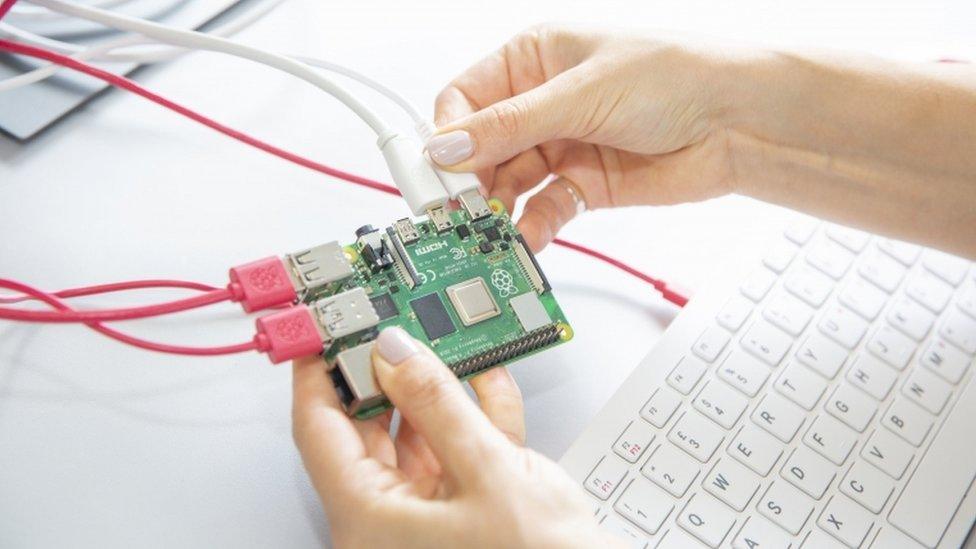

The latest version of the barebones computer is a significant upgrade - three times faster than the Raspberry Pi 3, which came out in 2016. Retailers report a lot of interest, with one telling me it sold out of all versions of the Pi within a few hours.

"It feels like a coming of age for us," says Raspberry Pi's founder Eben Upton. "It's 40 times as powerful as the original Pi and it's the first time that we're shipping a device that, for most users, will be subjectively indistinguishable from a traditional desktop computer."

What has also changed is that as well as the basic £34 model you can pay up to £54 for a device with more RAM - perhaps designed to be attractive to commercial users rather than schools.

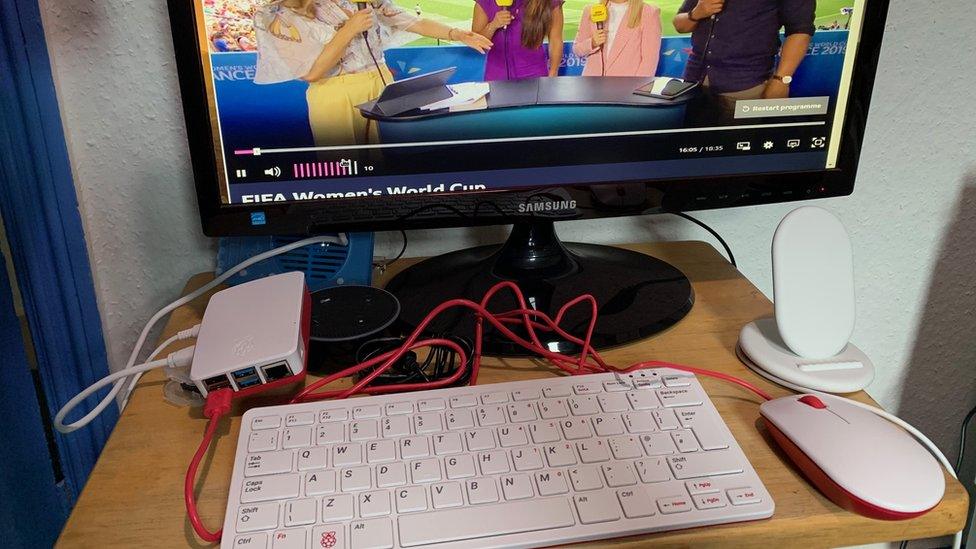

You can also pay more for kits with all you need to turn it into a desktop computer - something that seemed pretty daunting to some who bought early versions of the Pi for their children. I was supplied with a kit a few days ago, and over the weekend managed - without any help from a young person - to get it up and running and streaming the BBC iPlayer.

That more nuanced pricing policy tells you how this project has changed over the years as it has tried to steer a course, not always successfully, between its original educational mission and its unexpected triumph as a commercial business.

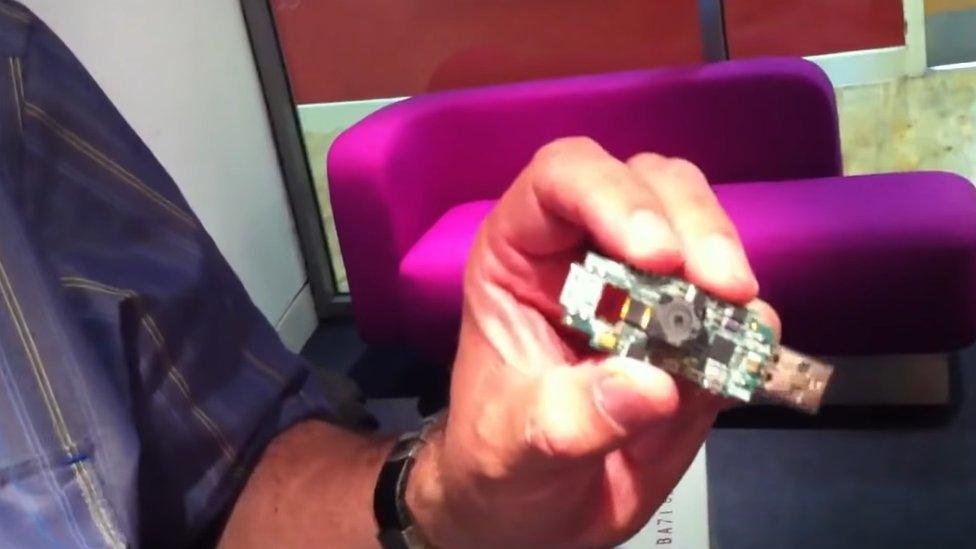

The prototype Pi was about the same size as a USB stick

Early days

I first came across the Raspberry Pi when Mr Upton and the Cambridge-based games entrepreneur David Braben came to my office in May 2011.

They brought with them a prototype about the size of a USB stick. They explained that they hoped it would cost around £15 and that schools would give it to children, with the aim of transforming the way they understood computing.

I thought it was an interesting if slightly sketchy idea and decided to shoot a video of the device on my phone and post it on YouTube., external Within days, tens of thousands of people had viewed the video, showing that this was a project which might well capture the imagination of the public.

And when the first Pi came out in 2012, it was indeed a huge hit, sparking interest from around the world. However, much of the enthusiasm came not from schools or teenagers, but from 40-something men with memories of learning to code with the BBC Micro or the Sinclair ZX Spectrum.

While some schools did start Raspberry Pi clubs, many struggled to integrate the device into a curriculum which was quite rigid when it came to how computing was taught.

The Pi 4 aims to be equivalent to a desktop computer

As sales boomed and companies discovered that the Raspberry Pi was a useful cheap device to employ in any number of manufacturing processes, it looked as though the project's original purpose might fade away.

But these days it seems to be back on track. The project was split into two, a commercial division and an educational foundation funded by the profits from sales of the Pi. In 2015 the Raspberry Pi foundation merged with Code Club and it now employs more than 100 people, compared with the 50 working on the commercial side.

Mr Upton, who runs the commercial division, is keen to stress that education is still at the heart of the project. "We hope to see the Raspberry Pi 4 in school computer labs, after-school clubs and children's bedrooms across the UK, and indeed the world."

With more competition and a long gap between models, Raspberry Pi sales have levelled off in the last couple of years. The hope now is that this new grown-up little computer, designed and built in the UK, will power the Pi and its mission forward again.

- Published24 June 2019

- Published7 February 2019

- Published25 April 2019