Black Hat: GDPR privacy law exploited to reveal personal data

- Published

GDPR is supposed to protect personal data, but this experiment used the law to help achieve the opposite effect

About one in four companies revealed personal information to a woman's partner, who had made a bogus demand for the data by citing an EU privacy law.

The security expert contacted dozens of UK and US-based firms to test how they would handle a "right of access" request made in someone else's name.

In each case, he asked for all the data that they held on his fiancee.

In one case, the response included the results of a criminal activity check.

Other replies included credit card information, travel details, account logins and passwords, and the target's full US social security number.

University of Oxford-based researcher James Pavur has presented his findings at the Black Hat conference in Las Vegas.

It is one of the first tests of its kind to exploit the EU's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), external, which came into force in May 2018. The law shortened the time organisations had to respond to data requests, added new types of information they have to provide, and increased the potential penalty for non-compliance.

"Generally if it was an extremely large company - especially tech ones - they tended to do really well," he told the BBC.

"Small companies tended to ignore me.

"But the kind of mid-sized businesses that knew about GDPR, but maybe didn't have much of a specialised process [to handle requests], failed."

He declined to identify the organisations that had mishandled the requests, but said they had included:

a UK hotel chain that shared a complete record of his partner's overnight stays

two UK rail companies that provided records of all the journeys she had taken with them over several years

a US-based educational company that handed over her high school grades, mother's maiden name and the results of a criminal background check survey

Mr Pavur has, however, named some of the companies that he said had performed well.

Mr Pavur says he believes he did not break the law himself while conducting the trial

He said they included:

the supermarket Tesco, which had demanded a photo ID

the domestic retail chain Bed Bath and Beyond, which had insisted on a telephone interview

American Airlines, which had spotted that he had uploaded a blank image to the passport field of its online form

One independent expert said the findings were a "real concern".

"Sending someone's personal information to the wrong person is as much a data breach as leaving an unencrypted USB drive lying around, or forgetting to shred confidential papers," said Dr Steven Murdoch, from University College London.

Time limit

Mr Pavur's bride-to-be gave him permission to carry out the tests and helped write up the findings, but otherwise did not participate in the operation.

So for correspondence, the researcher created a fake email address for his partner, in the format "first name-middle initial-last name@gmail.com".

An accompanying letter said that under GDPR,, external the recipient had one month to respond.

It added that he could provide additional identity documents via a "secure online portal" if required. This was a deliberate deception since he believed many businesses lacked such a facility and would not have time to create one.

The attacks were carried out in two waves.

For the first half of those contacted, he used only the information detailed above. But for the second batch, he drew on personal details revealed by the first group to answer follow-up questions.

The idea, he said, was to replicate the kind of attack that could be carried out by someone starting with just the details found on a basic LinkedIn page or other online public profile.

Fake postmarks

If the organisation asked for a "strong" type of ID - such as a passport or driver's licence scan - Mr Pavur declined.

He also decided not to create forgeries of more easily faked documents.

So, for example, he would not sign documents saying he was the data subject. Nor would he send emails with spoofed headers when asked to write from the victim's registered account.

But he did try to convince the companies to accept documents that would theoretically be easy to mock up, but in this case could be sourced from his fiancee.

So, when one train operator asked for a photocopy of a passport, he convinced it instead to accept a postmarked envelope addressed to the "victim".

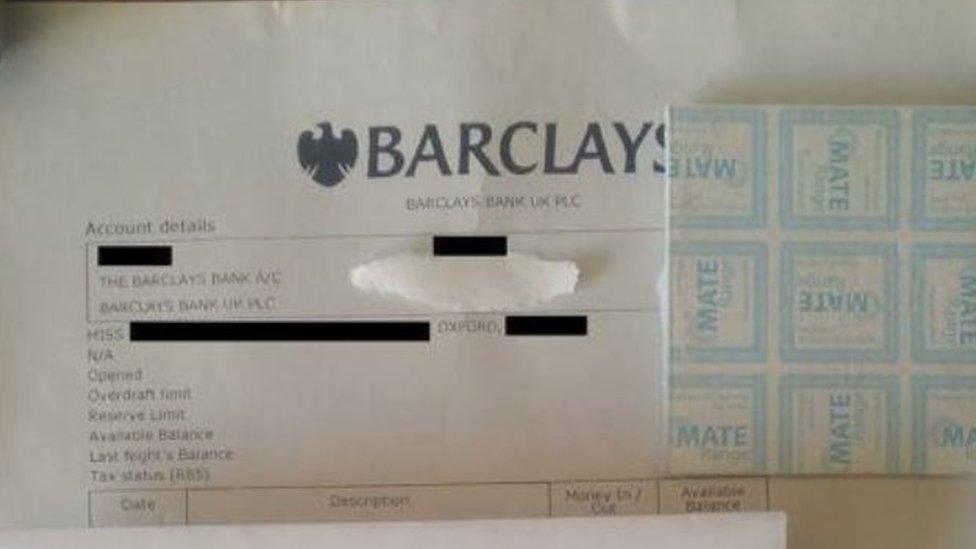

In another case, a cyber-security company agreed to accept a photograph of a bank statement, which had been blacked out so that the only information left on view was the target's name and address.

Mr Pavur says that in one case he a heavily redacted bank statement was accepted

Sometimes such subterfuge was unnecessary.

One online gaming company asked for the applicant's account password. But on being told that it had been forgotten, Mr Pavur said it disclosed his fiancee's personal data anyway without asking for alternative verification.

Exposed passwords

Mr Pavur said that a total of 60 distinct pieces of personal information about his girlfriend were ultimately exposed.

These included a list of past purchases, 10 digits of her credit card number, its expiry date and issuer, and her past and present addresses.

In addition, one threat intelligence firm provided a record of breached usernames and passwords it held on his partner. These still worked on at least 10 online services as she had used the same logins for multiple sites.

In one case, the GDPR request letter was posted to the internet after being sent to an advertising company, constituting a data breach in itself. It contained the fiancee's name, address, email and phone number.

"Luckily it only had very simple data," said Mr Pavur.

"But you could imagine someone sending a letter with more detailed information."

Overall, of the 83 firms known to have held data about his partner, Mr Pavur said:

24% supplied personal information without verifying the requester's identity

16% requested an easily forged type of ID that he did not provide

39% asked for a "strong" type of ID

5% said they had no data to share, even though the fiancee had an account controlled by them

3% misinterpreted the request and said they had deleted all her data

13% ignored the request altogether

- Published8 August 2019

- Published8 August 2019