Why are pupils switching off from computing GCSE?

- Published

Too few girls are choosing to do computing GCSE

If you think that computing skills are vital for Britain's economic future, there is worrying news in Thursday's GCSE results for England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

They show a drop of more than 40,000 in the numbers sitting for a qualification in either computing or ICT (information and communications technology). What is more, there is a growing gender gap, with boys outnumbering girls by more than three to one in choosing to take the subjects.

In 2019 a total of 89,542 students took either the ICT or the computing GCSE,, external compared with a combined total of 130,210 in 2018. Male entries totalled 68,965, compared with 20,577 girls taking the exams.

What all this reflects is something this blog has covered previously, the unintended consequences of the phasing out of the ICT exam in England - it was still taken in Wales and Northern Ireland this year - and its replacement by the far more challenging computing.

As the much derided ICT subject disappeared from the curriculum, it was hoped that schools and pupils would embrace the much more rigorous computing course, giving a big upgrade to the nation's digital skills.

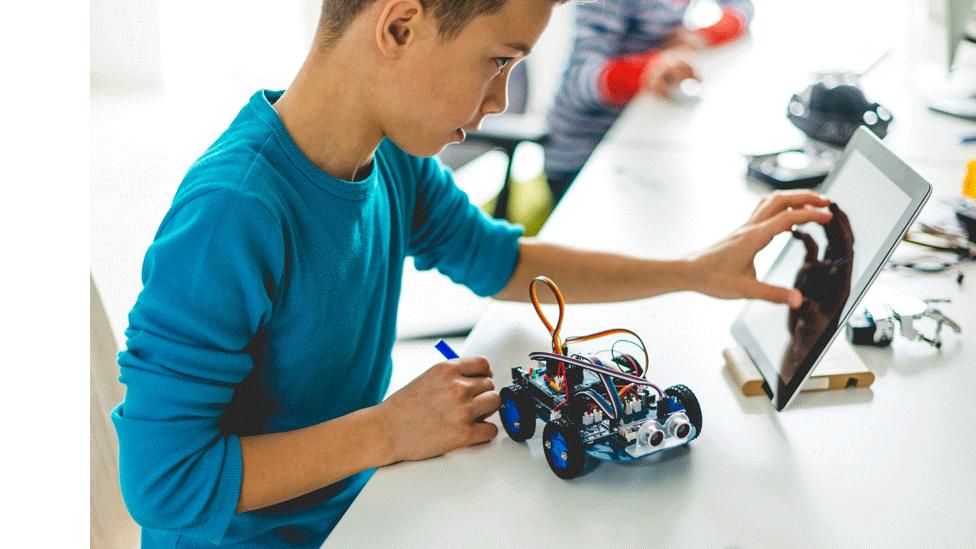

Schools are endeavouring to make computing more fun with lessons such as robot building

But that has not happened - at least not on the scale needed. While entries for computing have risen, they have come nowhere near matching the decline in the numbers studying ICT.

Meanwhile, the gender gap has opened up. Five years ago, girls made up about 40% of entries for the ICT exam, this year they accounted for only 21% of computing entries. The Joint Council for Qualifications hailed what it called a "significant rise in female entries in computing" in 2019, but that was from a very low base.

The evidence is that many schools are struggling to find the teachers needed to tackle this difficult course, and may not be too keen to persuade pupils to enter an exam where getting a decent grade will not be easy.

The computing exam may produce more of the high-end programming knowhow which the ICT course ignored, but for employers looking to recruit people with a wide range of tech skills, the GCSE figures are a concern.

"The digital skills gap in industry is fast expanding and already at a level that can't be filled quickly enough," says Agata Nowakowska, of Skillsoft, which provides workplace e-learning courses."We need to take action now to turn this around."

While the ICT course was criticised for teaching little more than how to use Microsoft Office, its defenders said it did provide a basic grounding in IT skills.

They argued that it could be revamped and retained as an option alongside the computing GCSE. They will now feel vindicated by this latest evidence that tech education is becoming a minority sport.

- Published22 August 2019

- Published22 August 2019