The Chinese suicides prevented by AI from afar

- Published

Li Fan, a 21-year-old student, attempted suicide after posting a brief message on the Chinese Twitter-like platform Weibo just after Valentine's Day.

"I can't go on anymore. I'm going to give up," he wrote.

Soon after, he lost consciousness.

He was in debt, had fallen out with his mother and was suffering from severe depression.

Some 8,000km (5,000 miles) away from his university in Nanjing, his post was detected by a program running on a computer in Amsterdam.

It flagged the message, prompting volunteers from different parts of China into action.

When they were unable to rouse Mr Li from afar, they reported their concerns to local police, who eventually saved him.

It might sound extraordinary but this was just one of many such success for the Tree Hole Rescue team.

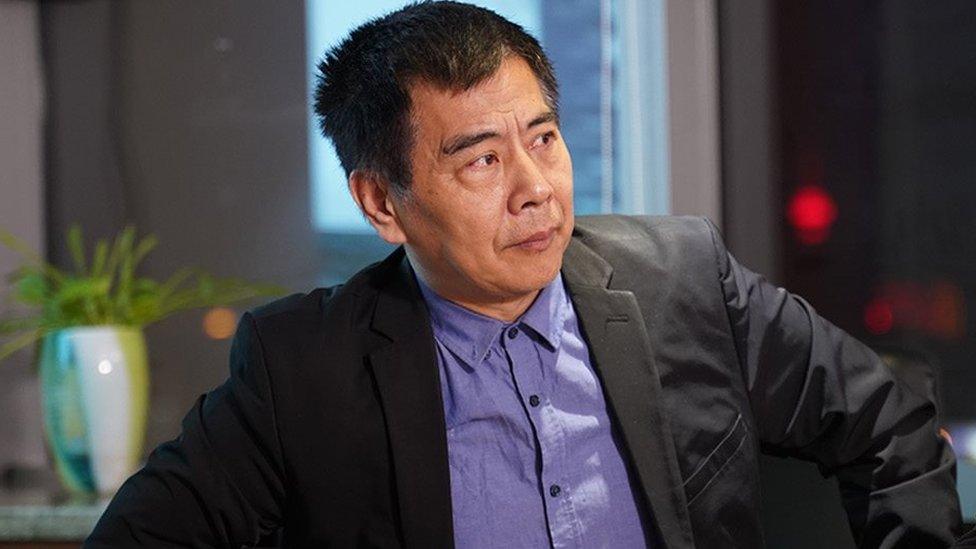

The initiative's founder is Huang Zhisheng, a senior artificial intelligence (AI) researcher at the Free University Amsterdam.

Huang Zhisheng created the Tree Hole Rescue effort

In the past 18 months, his program has been used by 600 volunteers across China, who in turn say they have rescued nearly 700 people.

"If you hesitate for a second, a lot of life will be lost," Mr Huang told BBC News.

"Every week, we can save around 10 people."

The first rescue operation was on 29 April 2018.

A 22-year-old college student, Tao Yue, in northern China's Shandong province, wrote on Weibo she planned to kill herself two days later.

Peng Ling, a volunteer from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and several others reacted.

Ms Peng told BBC News they had found a phone number for one of student's friends via an earlier post and passed the information to the college.

"I tried to message her before sleep and told her that I could pick her up," she said.

"She added me as a friend on [Chinese app] WeChat and gradually calmed down.

"Since then, I have kept check on her to see if she is eating. We also buy her a bunch of flowers through the internet once a week."

After this success, the team rescued a man who had tried to jump off a bridge and saved a woman who had tried to kill herself after being sexually abused.

"Rescues need both luck and experience," said Li Hong, a Beijing psychologist who has been involved for about a year.

Psychologist Li Hong says she has helped rescue about 30 people

She recalled how she and her colleagues had visited eight hotels in Chengdu, in order to locate a suicidal woman they had known had booked a room in the city.

"All the receptionists said they didn't know the woman," Ms Li said.

"But one of them hesitated for a moment. We assumed it must be that hotel - and it was."

So how does the system work?

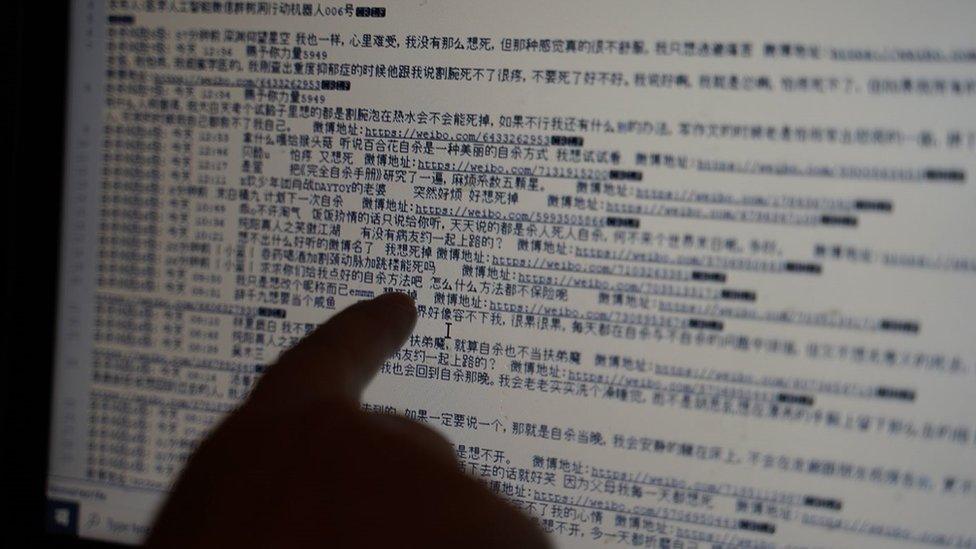

The Java-based program monitors several "tree holes" on Weibo and analyses the messages posted there.

A "tree hole" is the Chinese name for places on the net where people post secrets for others to read.

The name is inspired by an Irish tale about a man who confided his secrets to a tree.

One example is a post by Zou Fan, a 23-year old Chinese student who wrote a message on Weibo before killing herself, in 2012.

Huang Zhisheng's software proactively searches Weibo for certain keywords

After her death, tens of thousands of other users added comments to her post, writing about their own troubles, thus turning the original message into a "tree hole".

The AI program automatically ranks the posts it finds from one to 10.

A nine means there is a strong belief a suicide attempt will be made shortly. A 10 means it is likely to be already under way.

In these cases, volunteers try to call the police directly and/or contact the person involved's relatives and friends.

But if the ranking is below six - meaning only negative words have been detected - the volunteers normally do not intervene.

One of the issues commonly encountered by the team is a belief among older relatives that depression is not a "big deal."

"I knew I had depression when I was in high school but my mother told me that it was 'absolutely impossible - don't think about it anymore'," Mr Li told BBC News.

The AI program also found a post from a young woman, saying: "I will kill myself when New Year comes."

But when the volunteers contacted her mother, they said she had sneered and said: "My daughter was very happy just now. How dare you say she is planning suicide."

Even after the volunteers showed evidence of her daughter's depression, the mother did not take the matter seriously.

It was only after an incident in which the police had to stop the youngster jumping off a rooftop that the mother changed her mind.

Long journey

Despite its successes, Mr Huang acknowledges the limits of his project.

"Because Weibo limits the use of web crawlers, we can only gather around 3,000 entries every day," he said.

"So we can only save one or two a day on average and we choose to focus on the most urgent cases."

Another issue is that some of those rescued require a long-term commitment.

Volunteers sometimes find themselves checking up on rescued contacts over the course of weeks and months

"Most of my life now is occupied by these rescued people," Ms Li said.

"Sometimes I get very tired."

She said she was currently in contact with eight people who had been rescued.

"I have to reply [to] them soon after they send me a message," she said.

Some team members also try to provide help offline.

For example, one AI professor is said to have found a data-labelling job for one person found to have a social-anxiety disorder.

There is also the issue that suicidal thoughts can return.

Ms Peng gave the example of one youngster who had "looked better each day" after being rescued but then killed herself.

"She was talking to me about getting a new photo portrait on Friday," Ms Peng said, adding that two days later the woman was dead.

"It's a big shock to me that a person you got along with over a long time suddenly isn't there."

By contrast, Mr Li remains healthy and now works at a hotel.

"I like this job because I can communicate with many different people," he said.

He added while he was very appreciative of the rescue team's efforts, ultimately it was up to each individual to achieve a long-term solution.

"Different people's joys and sorrows are not completely interlinked," he said.

"You must redeem yourself."

Illustration designed by Davies Surya

At the request of the interviewees, the names of the rescued people involved have been changed.

If you have been affected by self-harm, mental health issues or emotional distress, help and support is available via the BBC Action Line.