General election 2019: Do social media ads work, are they fair?

- Published

In early November, we asked you to send us targeted election ads you had seen on social media. We've had a tremendous response, with more than 1,800 messages so far.

Looking through them, a number of questions arise. How are these ads targeted, do they work, and are new laws needed to control them?

Choosing the targets

Conventional wisdom suggests that social media advertising is powerful because it delivers precise targeting - thousands of different messages crafted to reach the right people in the right places.

It is ironic then that what looks like one of the more expensive campaigns during the election was anything but targeted.

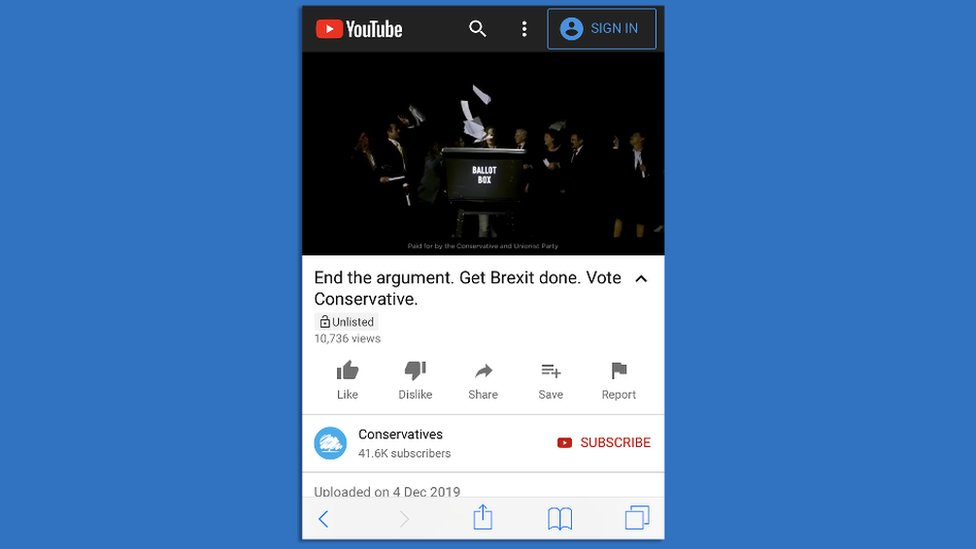

This Conservative ad eventually amassed millions of views

On Saturday, Sunday and Monday, the Conservatives splashed out on the masthead advert on YouTube's UK site. One message sent right across the country - the equivalent of buying a commercial slot in ITV's News at Ten 25 years ago.

Those of you who wrote in certainly noticed. A clutch sent in screenshots, with a couple saying it was the first election ad they had seen.

"An ad for the Conservatives popped up as I looked for Bob the Builder videos for my son," wrote one.

But on Facebook, the various parties have indeed experimented with targeting strategies.

In the early stages, it was hard to discern a pattern.

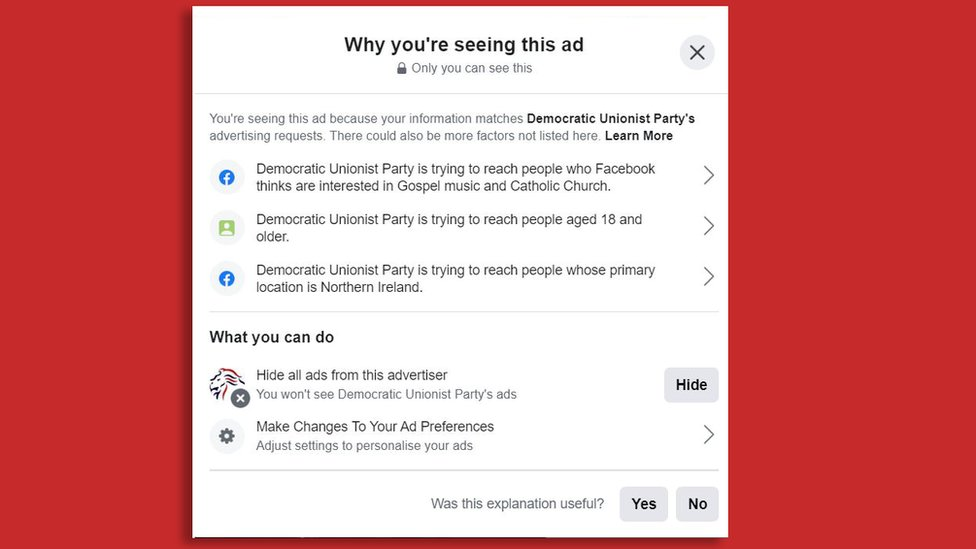

We saw ads aimed at Mock the Week viewers, at people interested in the Rugby World Cup, and even one from the Democratic Unionist Party aimed at people interested in gospel music and the Catholic church.

The DUP targeted one of their ads at adults interested in gospel music and the Catholic church

In the last week, however, it seems location, location, location has become the order of the day.

A few people wrote in to complain they were not seeing any ads - whereas others sent in half a dozen from different parties and campaign groups. The reason was a few key marginals have become the focus for spending, not just by the parties but by tactical voting groups.

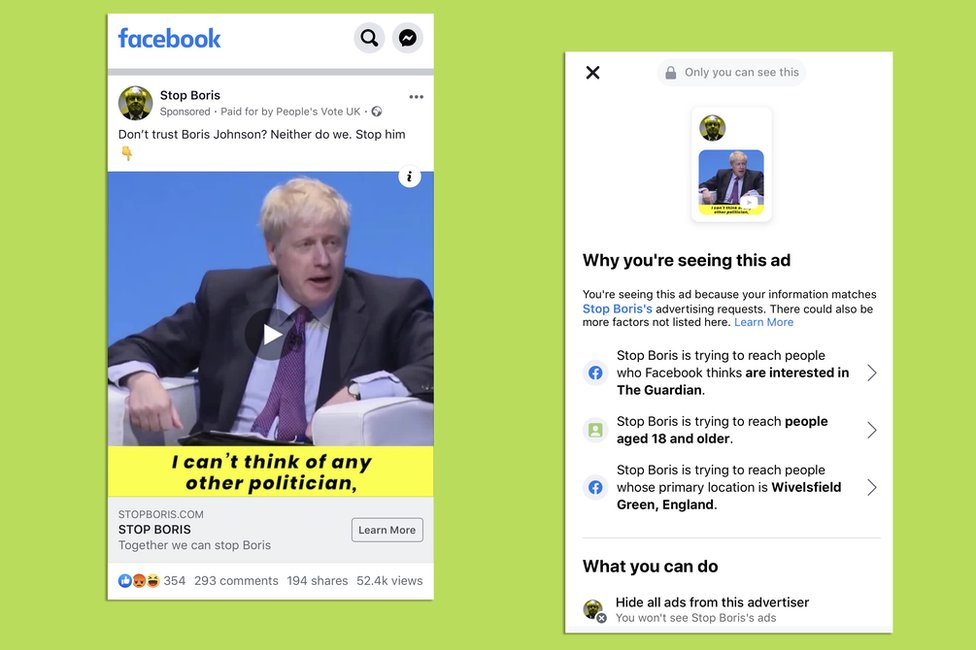

This ad was targeted at people interested in the Guardian newspaper whose primary location is Wivelsfield Green

Two such groups, Vote Smart and Stop Boris, targeted Wivelsfield Green, just one ward of the marginal Lewes constituency. Both groups urged voters to choose candidates who could beat the Conservatives.

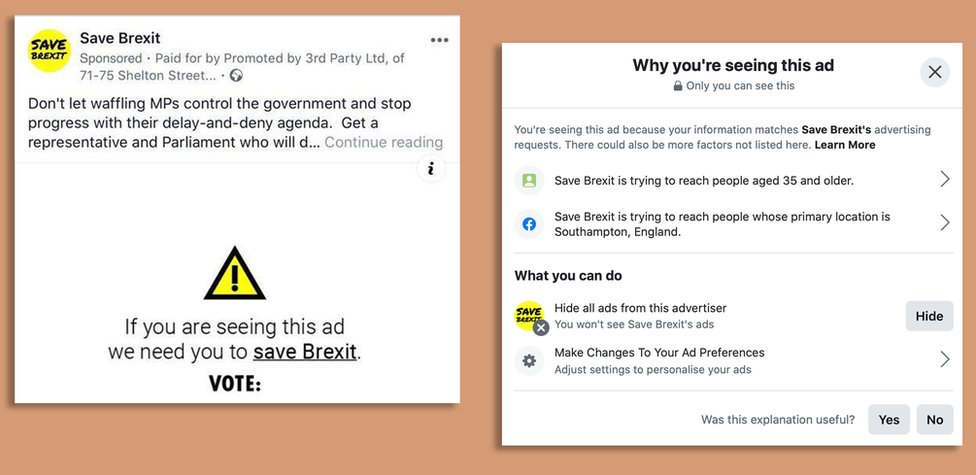

Meanwhile Save Brexit, funded by 3rd Party Limited - which is run by a former Vote Leave executive - has run ads in Southampton, Bassetlaw and Wakefield.

This ad was promoted to voters in Southampton aged 35 years and older

In each case, they claimed that voting Conservative was the only option for Brexiteers.

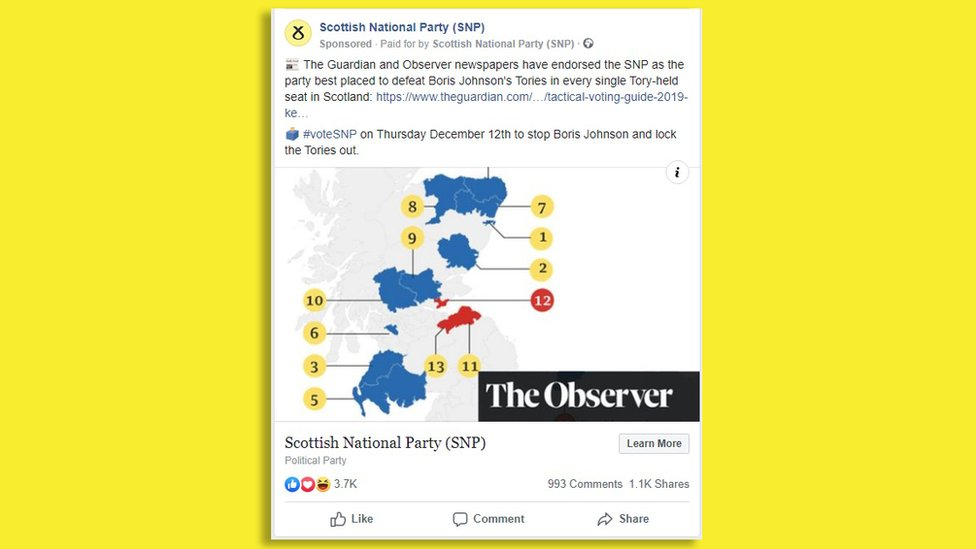

Both Labour and the SNP have also joined this game.

Labour has told voters in one marginal constituency "the LibDems can't win here", while the SNP said it was the party best placed to take Tory-held seats in Scotland.

The SNP referenced an article in the Observer newspaper in one of its ads

Does it work?

In each election, parties face the danger that they use tactics that worked last time round while the world has moved on.

Facebook played a big role in both the EU referendum and the 2017 general election, and campaigners from all sides have rushed to splurge their budgets on the platform this time.

But plenty of our contributors are sceptical about how well these ads have been targeted.

"My Facebook traffic tends to be middle-left to sometimes extreme," said a woman who received an ad from a group attacking Labour over its policies towards landlords.

"I have no interest in private schools," said someone who sent in an ad from Parents' Choice, which campaigns to keep their charitable status.

"Badly targeted: Ofsted doesn't exist in Scotland," said another about an ad from the same group.

Others said the advertisers had misfired.

"This is an interesting one, as it's targeting people in Durham but I live in Cambridge," said one.

And an ad for a Conservative candidate in the south-west caused amusement: "He seems to be targeting people in London even though he's standing [elsewhere]."

Is it fair?

It is rare to find people who profess to be enthusiastic about any kind of advertising. But social media ads during elections appear to be a particular concern.

Many objected to what they saw as falsehoods.

"Obviously biased and yet another attempt to put across fake news," was one reaction to an advert from a non-party organisation.

There was also anger about bar charts giving a misleading impression about the state of the parties in specific constituencies.

And some of you objected to Tory estimates of the cost of Labour policies.

But the biggest concern was about a lack of transparency in adverts from groups set up as non-party campaigners.

At the beginning of this exercise, we were sent an ad from the Fair Tax Campaign. It broke Facebook's rules by omitting information about who had paid for it.

That ad was taken down until the campaign, started by a former Boris Johnson aide, complied with Facebook's rules.

A clutch of other groups did reveal who had paid for them, but there was still dissatisfaction.

It is still unclear who or what are:

Centrum Campaign, which funded Remain United's ads

Represent US, the funder of Vote Smart

Capitalist Worker, which paid for... Capitalist Worker

Just yesterday, a group called Lib Dems 4 Corbyn appeared with an advert that actually warned of the dangers of Jeremy Corbyn.

This ad attacked both the Lib Dems and Labour's leader

We asked Facebook whether a group claiming a false connection with the Liberal Democrats broke any rules.

After thinking about it for a while, the company said no.

It is hard to see new rules governing misinformation in online ads being introduced so long as it is allowed in leaflets, posters and party political broadcasts.

Sam Jeffers is co-founder of Who Targets Me, which also collects examples of targeted election ads. He wants more transparency.

"Even journalists are finding you have to head off to the Information Commissioner's Office or Companies House or the Electoral Commission to find out who's behind an ad," he says.

"It's not sensible for the average voter to have to do that."

He also thinks social media platforms need to be explicit about when ads are directed at an individual constituency, and how much is spent on them.

"You have national parties messing about with the spirit of electoral law by targeting spending at a constituency but not specifically mentioning the candidate," he says.

He is not alone in calling for reform.

"We need to confront the fact that our electoral law is not fit for purpose in the digital age," wrote the chairman of the Culture, Media and Sport Select Committee, Damian Collins, back in September.

The changes he wanted did not come in time for this campaign.

There will be plenty of inquests about the role of social media - and Facebook in particular - after the election.

But a new government may look back and conclude that its mastery of the dark arts of online campaigning delivered its victory.

How urgently then, will it press for reform?

Follow election night on the BBC

Watch the election night special with Huw Edwards from 21:55 GMT on BBC One, the BBC News Channel, iPlayer

As polls close at 22:00, the BBC will publish an exit poll across all its platforms, including @bbcbreaking, external and @bbcpolitics, external

The BBC News website and app will bring you live coverage and the latest analysis throughout the night

We will feature results for every constituency as they come in with a postcode search, map and scoreboards

Follow @bbcelection, external for every constituency result

From 21:45 GMT, Jim Naughtie and Emma Barnett will host live election night coverage on BBC Radio 4, with BBC Radio 5 live joining for a simulcast from midnight