What happens when the internet vanishes?

- Published

From his high-rise desk overlooking the sprawling city of Addis Ababa, Markos Lemma has a pretty good view.

As the founder of technology innovation hub IceAddis, his co-working space is usually abuzz with wide-eyed entrepreneurs fuelled on strong coffee and big dreams.

But when the internet shuts down, everything is stopped in its tracks.

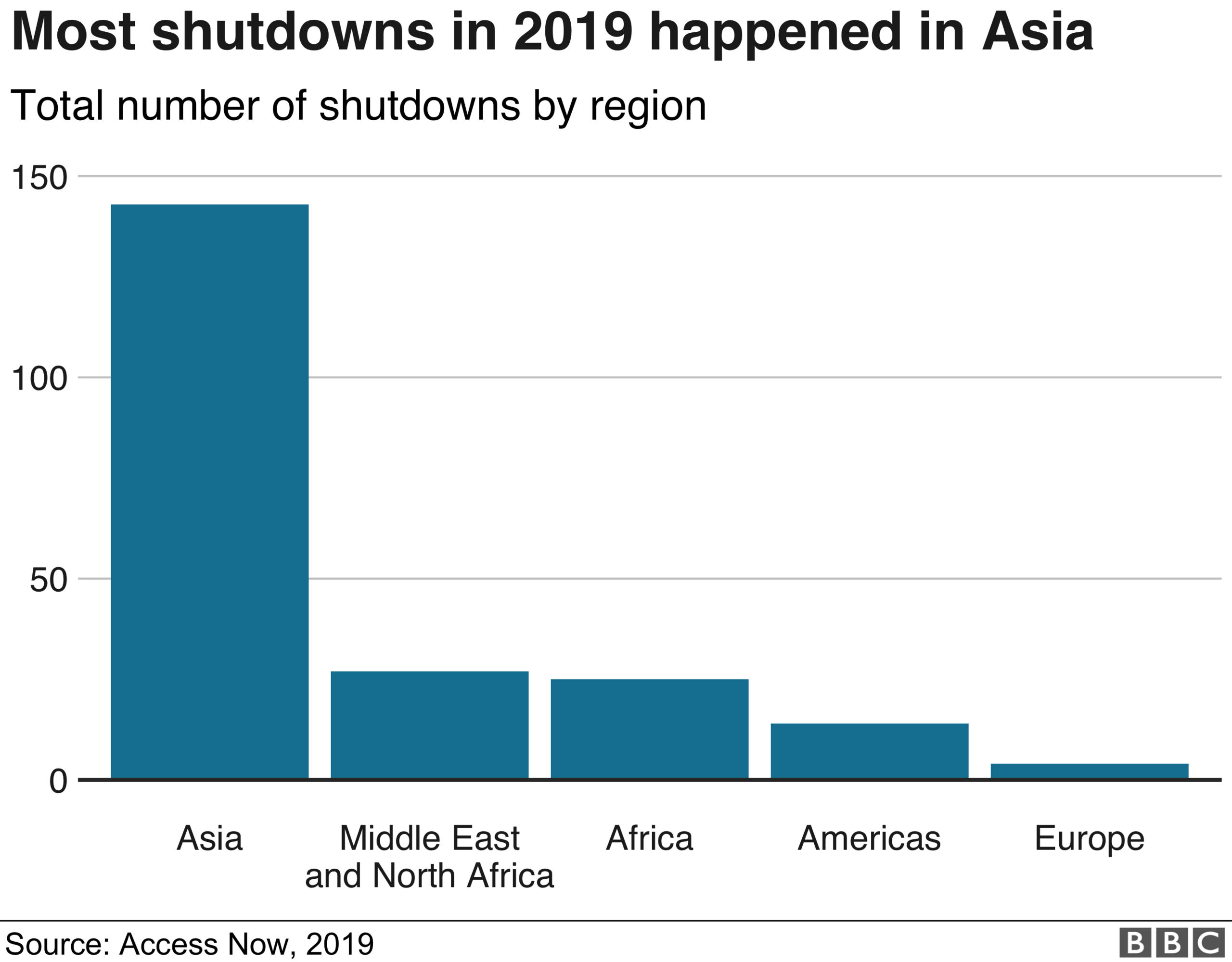

Data shared with the BBC by digital rights group Access Now, shows that last year services were deliberately shut down more than 200 times in 33 separate countries.

This includes, on one occasion, in the UK.

In April 2019 the British Transport Police shut down the wi-fi on London's Tube network during a protest by climate change activists Extinction Rebellion.

Also revealed in the report about shutdowns in 2019, external:

The internet was switched off during 65 protests in various countries around the world

A further 12 took place during election periods

The majority of all shutdowns occurred in India

The longest internet switch-off happened in Chad, central Africa, and lasted 15 months

In Addis Ababa, everything stops, says Markos Lemma.

"No one comes in - or when they do they don't stay for long because without the internet, what are they going to do?

"We had a software development contract that was cancelled because we couldn't deliver on time, because... there was internet disconnection. We've also [had] situations where international customers think our businesses are ignoring them, but there's nothing we can do. "

Markos Lemma in front of a logo for his co-working space IceAddis

Motorbike drivers wait around, rather than delivering food. Without an internet connection, people cannot order online or on apps, says Markos.

"Internet shutdowns have a direct consequence on businesses and people here."

Disconnecting the web

It is not just Ethiopia, and the impact is not only economic. Access Now's research shows that blackouts are affecting tens of millions of people all over the world in various ways.

Government officials are able to "switch off" the internet by ordering service providers to block certain areas from receiving signals - or sometimes, by blocking access to specific web services.

Human rights groups are concerned that the measure is becoming a defining tool of government repression around the world.

This new data analysed by the BBC suggests that disruption is increasingly linked to times of protest.

Governments often say a shutdown is to help ensure public safety and to stop the spread of fake news.

But critics say they stifle the flow of information online – and crack down on any potential dissent offline.

The UN declared internet access to be a human right in 2016, and achieving universal access is one target of its Sustainable Development Goals.

However, not all leaders subscribe to that idea.

In August 2019, Ethiopia's Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed declared that the internet is "not water or air" and that shutdowns would remain an important tool for national stability.

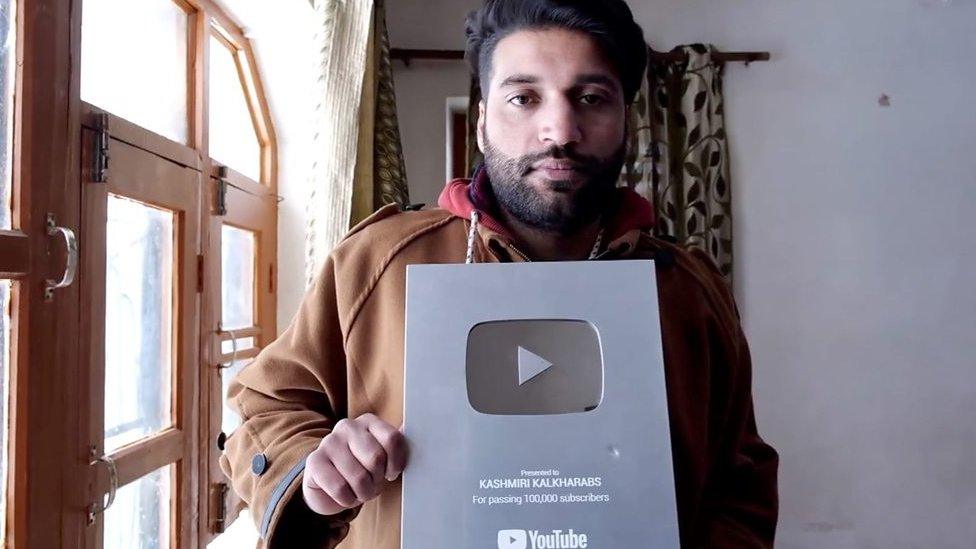

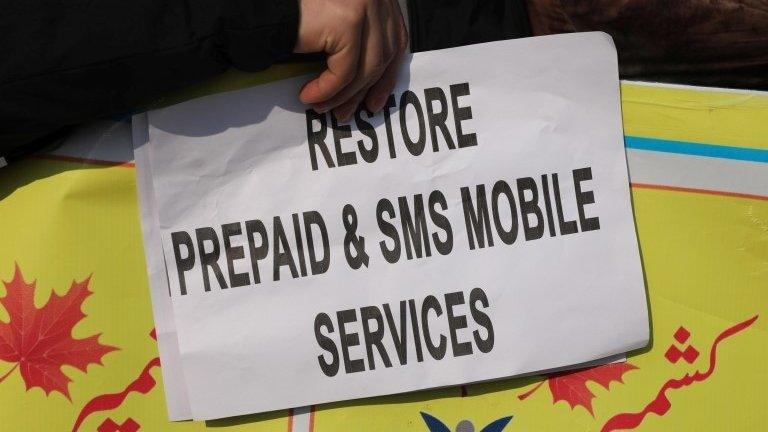

The YouTubers stuck offline in India-administered Kashmir

Markos Lemma is angry about that.

"The government doesn't see the internet as important. I think they really think the internet is just about social media, so they don't really see the economic value of the internet and how that impacts the economy."

India tops the blackout list

The new data for 2019 shows that India had by far the highest number of shutdowns of any country last year.

Mobile data or broadband services were switched off for residents in various parts of the country 121 times, with the majority (67%) occurring in disputed India-administered Kashmir.

And protesters in Sudan and Iraq found themselves forced to resort to organising everything offline when their internet was turned off.

June 2019: Did an internet blackout kill Sudan's revolution?

The impact of each incident varies greatly depending on the scale of the outage: from localised blocking of social media platforms to countrywide outages of all internet traffic.

"Throttling" is a form of blackout that is harder to monitor, and happens when a government slows down data services. They might bump modern, fast 4G, mobile internet down to 1990s-era 2G, making it impossible to share videos or livestream.

This happened in May 2019, when the President of Tajikistan admitted to throttling most social networks. including Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, saying they were "vulnerable to terrorist activity".

Some countries, like Russia and Iran, are currently building and testing their own versions of a locked-off nationwide internet, thought to be a sign of increased control on the web.

Digital rights group Access Now says: "It seems more and more countries are learning from one another and implementing the nuclear option of internet shutdowns to silence critics, or perpetrate other human rights violations with no oversight."

- Published19 December 2019

- Published10 January 2020

- Published14 January 2021

- Published26 November 2019

- Published22 February 2020

- Published24 December 2019

- Published28 January 2020