Coronavirus: How easy it for the UK to make more ventilators?

- Published

British engineering firms have been called on to switch to making medical ventilators as concern grows about the effects of the coronavirus pandemic.

For patients critically ill with Covid-19, access to a ventilator could be a matter of life or death. The machines get oxygen into the lungs and remove carbon dioxide from the body when people are too sick to breathe on their own.

That might sound simple but it is crucial to keep pressure to a minimum to avoid causing further damage. In addition, if the oxygen level is too high, that can do harm.

As a result, intensive care unit (ICU) ventilators need to not only keep people breathing but also accurately monitor their lungs, using a mix of airflow, temperature, humidity and pressure sensors. Hospitals across the world now urgently need more of this kit.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

In the UK, the government is speaking to a wide range of manufacturers to see if they can lend a hand. The goal is to have "many times" the current number - about 20,000 additional machines as quickly as possible.

"The fact the government is asking manufacturers to make a different product to what they normally make is unprecedented since the World War Two," Justin Benson, from the consultancy KMPG, said. "It's a relatively complex piece of equipment with lots of components and a dedicated supply chain. So asking someone who makes a car to produce a respirator would take them some time."

Others are more plain spoken about the idea ventilator assembly lines could be established at places such as, external Honda's Swindon plant.

"It would take too long," said Stephen Phipson, chief executive of the engineering trade body Make UK. "We already have companies that build other people's designs for them - everything from alarm systems to signalling systems for trains. These are the companies you need, which can place components on circuit boards, do the wiring, testing and assembling. Building cars is a very different matter."

'Ready and willing'

So while big name manufacturers such as Rolls-Royce and JCB have also been invited to discuss playing a role, it could be lesser known companies that take the lead.

Gloucestershire-based Renishaw is one to have already been approached by the Cabinet Office. The company makes small precision-measurement parts, which are used in other types of medical equipment as well as aircraft.

ICU ventilators use touchscreens to provide a range of tools to assess the appropriate respiratory therapy

"We're still trying to understand the medical device requirements," said spokesman Chris Pockett. "But we're willing and want to contribute to the national effort."

Woking-headquartered TT Electronics is another potential contributor. It makes speciality coils and ultra-fine wound wire for radiation therapy equipment and surgical navigation devices.

Although its involvement with ventilators has been limited to producing power supplies, a spokeswoman said it was "ready to help in any way that we can".

Other parts, however, may still need to be sourced from further afield. This is where companies such as Dyson might have a role to play, suggested Make UK, helping to ensure supplies of semiconductor chips and other parts that would be too complex to make locally.

"It takes us a matter of weeks to scale up a factory to assemble something but sometimes the lead time on these components can be months," said Mr Phipson. "So making sure that that point is covered off first, which is the priority, is really important."

A spokeswoman for Dyson said it was already "working with other companies to see if we can provide a rapid solution".

Safety checks

It typically takes two to three years to develop and launch a ventilator. So convincing the industry's big players - such as General Electric and Philips - to let their products be made locally under licence is the likely plan of action.

However, there would still be other hurdles to overcome. Abingdon-based Penlon already makes a bulkier type of ventilator used during anaesthesia. Its marketing chief, Craig Thompson, warned bureaucracy may be the biggest challenge of all.

"Ventilators are less sophisticated than things like smartphones and Xboxes," he said. "This is not a technical challenge but a regulatory compliance one."

Even if a ventilator used an existing design, he said, it still needed to undergo rigorous testing if made at a new site.

And following that, there was usually a long wait for the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency to sign off the product.

Under normal circumstances, all this typically takes a year.

"The purpose of the process is to make sure that the device is effective and safe, and it takes a long time," Mr Thompson said.

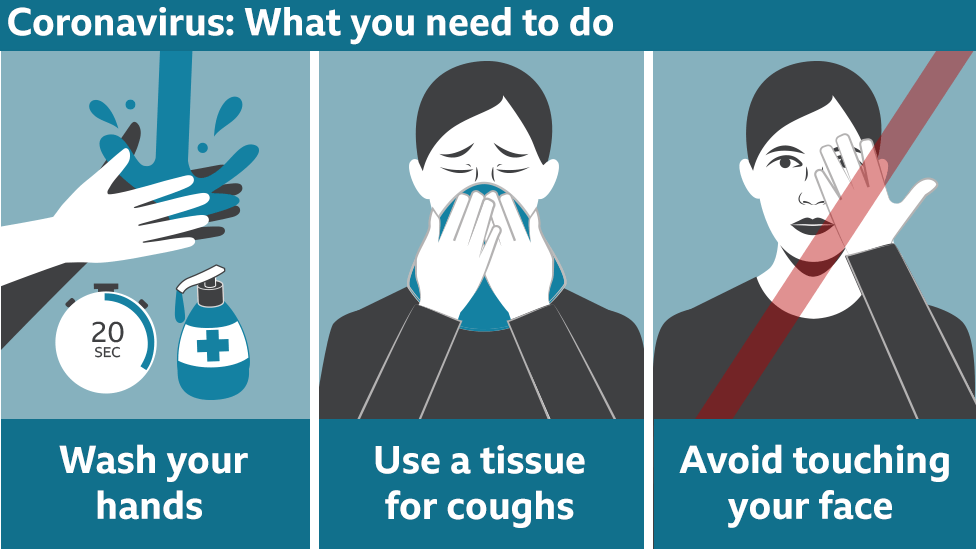

EASY STEPS: How to keep safe

A SIMPLE GUIDE: What are the symptoms?

GETTING READY: What's the UK's plan?

TRAVEL PLANS: What are your rights?

IN-DEPTH: Coronavirus pandemic

And even an expedited procedure would probably still take too long.

"The NHS is looking for a solution for this crisis in the next six to eight weeks," he said. "The only way you can make that requirement would be to source them from existing factories, so definitely not from the UK."

Make UK was more optimistic and suggested such a regulatory impasse could be overcome if there was enough political pressure. But it too warned making the kinds of numbers of ventilators the NHS needed may not be possible in the timescale desired.

"You could end up with some components taking 20 weeks to deliver," said Mr Phipson. "We need to go through the detail and work out what is possible. We should have a clearer picture by the end of the week."

- Published16 March 2020