Coronavirus: Under surveillance and confined at home in Taiwan

- Published

Milo Hsieh is an American University student living in Taiwan under quarantine. The BBC asked him to write this article after one of his tweets about having his movements tracked by a satellite-based system, external was widely shared.

I did not expect two police officers to come knocking at my door at 08:15 when I was still asleep in my bed on Sunday morning.

My phone briefly ran out of battery at 07:30, and in less than an hour, four different local administrative units had called. A patrol was dispatched to check my whereabouts. A text was sent notifying that the government had lost track of me, and warned me of potential arrest if I had broken quarantine.

I returned to Taiwan last Thursday to experience the island's zero-risk take on coronavirus.

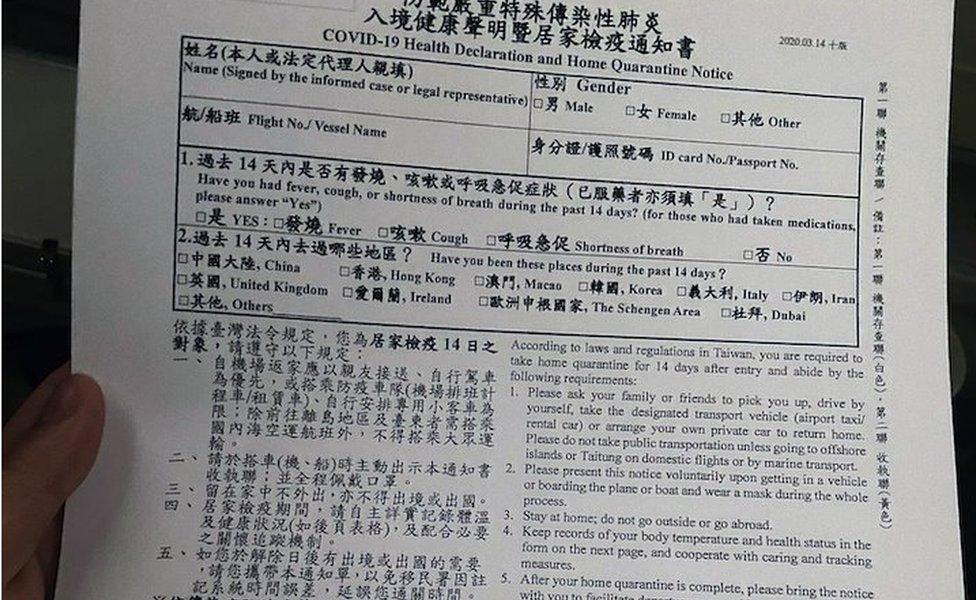

Since I was coming back from Europe, I am subjected to a mandatory 14 days home quarantine. Before I had my passport checked, I had to pass through a booth set up by the Ministry of Health and Welfare. I filled out a document detailing places I had visited in the last fortnight, my phone number, landline and address. They notified me that my phone would be "satellite-tracked" for enforcement.

The level of precaution taken in Taiwan is nothing like what I saw in Europe.

People flying back into Taiwan must go into 14 days of quarantine to help combat the spread of coronavirus

During the initial phase of lockdown in Belgium, which I had to leave after my study programme was cancelled, people still went out and lined up at fast food kiosks. Even as an outbreak was happening in northern Italy, I saw during my visit to London in the first weekend of March, that people were still going to pubs.

Here, I am not allowed to step outside the apartment. I was not allowed to take public transport on my way back, and had to take special "quarantine taxis." My entire family has to quarantine with me for two weeks. This includes Biscuit, our dog.

How does Taiwan's system work?

The island refers to its phone-tracking system as being an "electronic fence".

Rather than ask users to download a special app or wear a location-transmitting wristband - as has been the case in some East Asian countries - it uses existing phone signals to triangulate the owner's locations.

To ensure users comply, an alert is sent to the authorities if the handset is turned off for more than 15 minutes. More than 6,000 people subjected to home quarantine are simultaneously tracked this way.

And to check that the phone has not simply been left behind, officials phone users up to twice a day to check they have their mobile to hand, and to ask about their health.

Recently, many Taiwanese, especially students, have returned to the island, as their schools overseas have closed and life around the world has ground to a halt. Some see the mandatory quarantine they have to go through as a necessary measure.

Frank Tseng is among them. He is one of my friends at American University, and he recently returned from Washington DC.

Arrivals to Taiwan have to sign a pledge saying they will stay behind closed doors for a fortnight and keep a record of their temperature

"I feel like even though it's a pain for the citizens who are coming back, I understand that it's a necessary process many of us have to take to go home," he told me.

But some see the enforcement mechanism as problematic.

Paul Huang, a local freelance journalist who was working abroad, decided to not go back to Taiwan because of surveillance fears.

"The government openly stated your phone will be digitally tracked to enforce quarantine - in the same way the authority usually tracks suspected criminals," he explained.

"Except this time they don't have or need a court-issued warrant to spy on your phone.

"You are being suspected of a crime by virtue of having travelled overseas."

LIVE: Latest updates

A SIMPLE GUIDE: What are the symptoms?

AVOIDING CONTACT: Should I self-isolate?

LOOK-UP TOOL: Check cases in your area

MAPS AND CHARTS: Visual guide to the outbreak

Paul has published articles critical of the Taiwan government in the past, including one calling its military a "hollow shell", external.

When entering the border, I was only notified that my phone would be tracked and that the local township official would give me a call daily. I was not made aware of any rights I had and did not sign documents consenting to surveillance.

As cases of the virus rise in Taiwan, the people seem to have entrusted the government with more power to contain the pandemic.

Metro station staff in Taiwan have used thermal scans to try to detect passengers who have the virus

But as the Taiwan government showcases its mass surveillance capability amid the crisis, it brings into question how it can be used in the wrong hands.

Brian Hioe, who runs New Bloom, a left-leaning publication focused on Taiwan, shared this concern with me.

His worry is that "the state may retain its expanded powers and continue with surveillance practices once the crisis has passed".

At the same time, despite analysis by some that Taiwan's alleged culture of obedience makes it easier to empower the state to contain the outbreak, Brian and I both agree that the vibrant civil society will readily fight back if the government oversteps its power.

At the end of the day, I will be staying home to complete my mandatory 14 days of home quarantine without being too paranoid about what the government knows or does not know about me.

But I do feel a little uncomfortable knowing that my neighbour could turn me in to the police if they see me outside of my apartment door, doing something as simple as taking out the trash.

- Published23 March 2020