Coronavirus: UK contact-tracing app 'ready in two to three weeks'

- Published

- comments

Building a coronavirus contact-tracing app that might help the UK emerge from lockdown has been a titanic effort - and it has largely taken place in private.

But now the NHS chief responsible has told MPs he hopes the first version will be ready in a fortnight's time.

Matthew Gould also disclosed plans to log the location of whenever two or more people are in close proximity for minutes at a time.

That will disturb privacy campaigners.

However, NHSX - the health service's digital innovation unit - has told BBC News this extra request will be "opt in" rather than the default setting.

Mr Gould told the Science and Technology Committee the app would be "technically ready" for deployment in "two to three weeks" - but made it clear it was only one part of the strategy to emerge from lockdown and would involve a none-too-subtle marketing campaign.

"If you want to protect the NHS and stop it being overwhelmed and, at the same time, want to get the economy moving, then the app is going to be part of an essential part of a strategy for doing that," he said.

On Monday, BBC News revealed the NHS had opted not to use the Google-Apple system.

The technology giants want to help apps taking a "decentralised" approach to operate more effectively, with contact-matching happening locally on phones.

Instead, the UK's app, unlike many countries in Europe, will use a "centralised" model, with the process of linking those diagnosed with the virus with those they could have infected happening on a computer server.

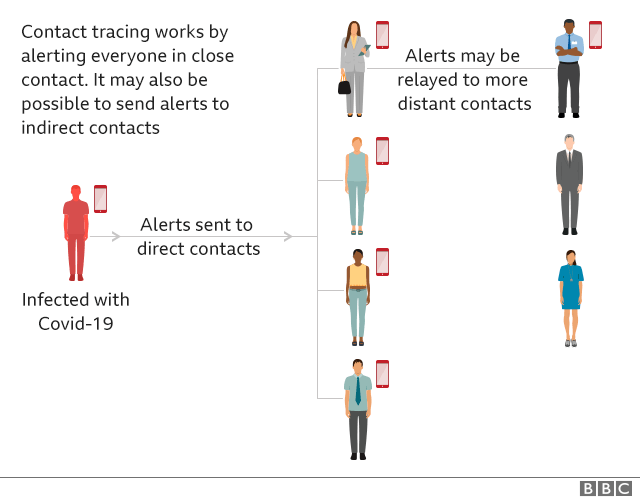

WATCH: What is contact tracing and how does it work?

Mr Gould told the committee there was a false dichotomy, where decentralised was seen as private and centralised was not.

And the NHS approach "allows you to do certain important things that you couldn't do if it was just phone-to-phone propagation".

For example, it would be easier:

to spot people falsely claiming to have virus symptoms so their friends would have to self-isolate

once someone had received a negative test result, to tell people advised to self-isolate because they had been in proximity with them to go out again

Meanwhile, Prof Christophe Fraser, whose advice has been crucial to the app's design, told the committee only a centralised approach would give epidemiologists visibility into how effective the app was proving to be and the means to calibrate it further.

Both men stressed any data collected would be anonymous.

But Mr Gould said "it would be very useful epidemiologically" - potentially identifying hotspots where "the virus was propagating" - if, in a update to the app, people voluntarily revealed where their proximity contacts had happened.

And it is not clear whether those they had had the contact with would have any choice about being tracked in a way that could end up creating a huge database of the movements of millions of people.

Prof Lilian Edwards, a leading expert on privacy law, told the committee there was an intrinsic risk in building a such a centralised database, which might be retained in some form beyond the pandemic.

The experts and many of the MPs took part in the hearing remotely, to minimise their risk of catching the virus

The target of persuading 80% of smartphone users to use the app would be virtually impossible without the 20% of the population polls suggested were worried about privacy, she said.

Although, it could effectively become compulsory if its use was made a condition of employment or admission to places such as football stadiums.

Greg Clark, who chairs the committee, meanwhile, suggested people may not take the app with them to the supermarket if they risked being told to stay home for two weeks because of a brief contact with someone infected.

Later at the daily Downing Street briefing, Health Secretary Matt Hancock confirmed he intended for 18,000 human contact tracers, whose work will complement the software, to be in place "before or at the same time as the app".

A SIMPLE GUIDE: How do I protect myself?

AVOIDING CONTACT: The rules on self-isolation and exercise

HOPE AND LOSS: Your coronavirus stories

LOOK-UP TOOL: Check cases in your area

TESTING: Can I get tested for coronavirus?