Coronavirus: France's virus-tracing app 'off to a good start'

- Published

- comments

Digital Minister Cedric O said the app had got off to a "very good start"

France's digital minister has said its coronavirus contact-tracing app has been downloaded 600,000 times since it became available on Tuesday afternoon.

StopCovid France is designed to prevent a second wave of infections by using smartphone logs to warn users if they have been near someone who later tested positive for the virus.

But a last-minute launch delay led some citizens to download the wrong product.

England has yet to confirm when its own app will roll out nationwide.

Health Secretary Matt Hancock had originally said it would be by 1 June, and then later suggested it would be around the middle of next week.

But the BBC has learned that it is now unlikely to be before 15 June and could be as late as the start of July.

That is in part because of delays in releasing a second version of the software to the Isle of Wight, where it is being trialled.

The update will add symptoms including the loss of taste and smell to a self-diagnosis questionnaire next week, or soon after.

It will also start giving at-risk users a code to enter into a separate website when they book a medical test. This will allow the result, saying whether they tested positive or negative, to be delivered back to them via the app.

Rival models

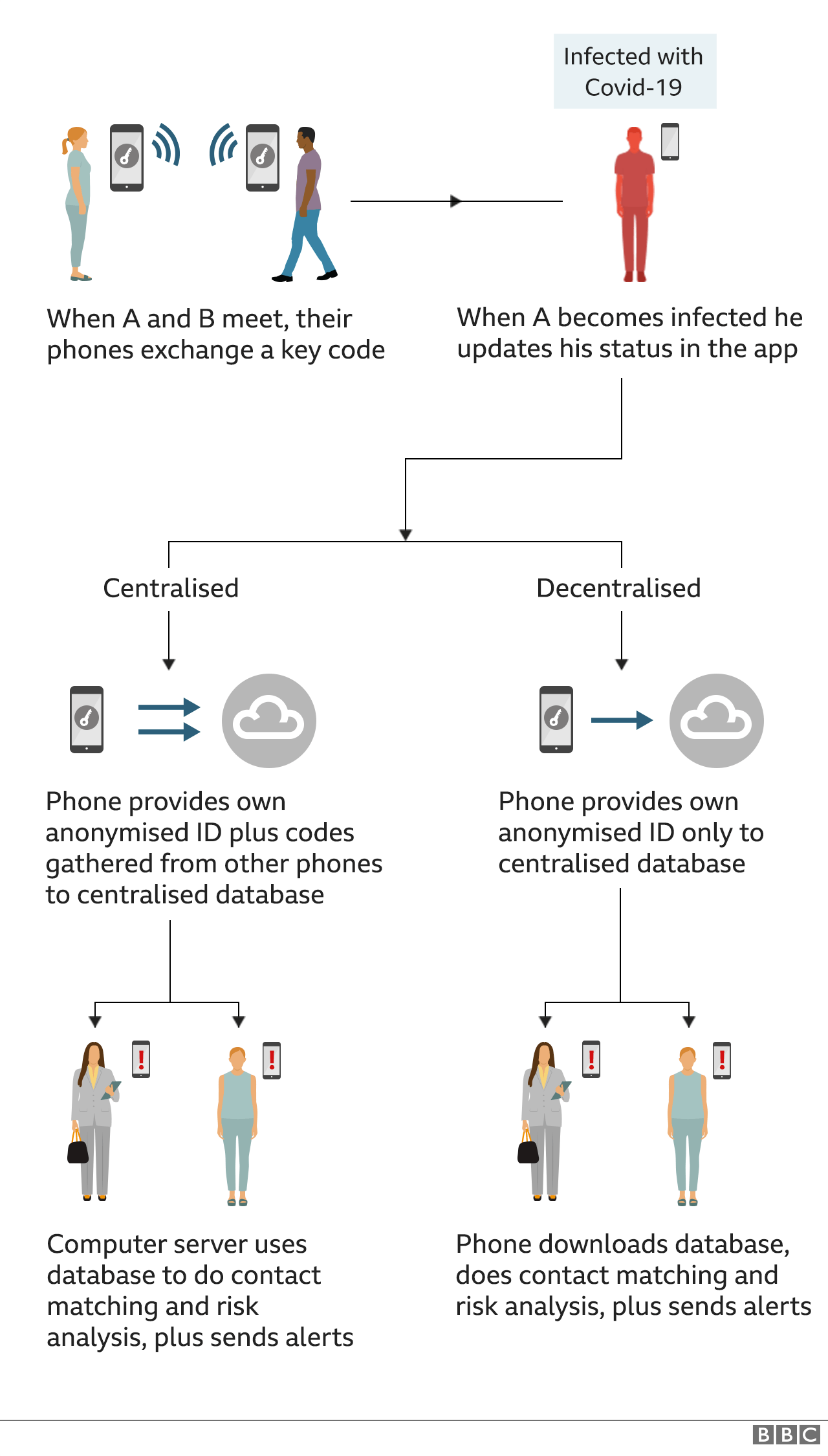

Both the UK and France have created apps of their own based on a "centralised" design.

By contrast, Latvia, Italy and Switzerland have released apps based on a "decentralised" technology developed by Apple and Google.

Advocates of the centralised approach says it gives epidemiologists more data to analyse, helping them better target the contagion alerts. They are also not limited by rules imposed by the two tech companies, such as a ban on being able to gather location data.

Supporters of the decentralised model say it better protects users' anonymity and privacy.

StopCovid France's rollout has caused controversy.

Hundreds of academics signed a letter in April raising concerns that gathered data could be repurposed for mass surveillance purposes.

There was then a row over the government's refusal to give MPs a vote on the matter, which was only resolved after ministers gave the Senate and National Assembly non-binding votes.

They both ultimately gave the app the green light. And the country's data privacy watchdog also approved the rollout after carrying out its own review, although it did ask for some changes to the app's wording.

WATCH: What is contact tracing and how does it work?

But questions remain about how many people will voluntarily install it - the more that do so, the better it should work.

Digital Minister Cedric O indicated that he was pleased with the initial uptake.

"As of this morning, 600,000 people managed to download the app, so it's a very very good start," he told the TV channel France 2.

"We are very happy with his start, but obviously several million French people need to have it."

He declined to give an exact target. But he had previously said a publicity campaign would initially focus on city-dwellers, external - particularly those using public transport, restaurants and supermarkets at peak times - as they were among those most likely to spread Covid-19.

Hours late

The French government had said the app would be released at midday on Tuesday.

But StopCovid France did not appear on Google Play until late on Tuesday afternoon, and then a few hours later on Apple's App Store.

One consequence of this was that a Catalan health information app with a similar name - Stop Covid19 CAT - was mistakenly downloaded by many in the interim, causing it to briefly top France's download charts.

A Catalan Covid-19 app was mistakenly downloaded by many after a last-minute delay

The only explanation given for the delay was that last-minute "technical adjustments" had to be made.

Contact tracing apps are supposed to complement work done by humans quizzing those diagnosed with the disease. It remains unclear whether the limitations of relying on Bluetooth can be overcome to avoid capturing too many false flags.

Baroness Dido Harding, who heads up the government's Test and Trace programme, said little new about the app when she appeared before the House of Commons' Health and Social Care Committee, beyond saying it was a "high priority" to link it to medical test results.

But Prof Christophe Fraser, who advises the NHS on the project, told MPs there was a "need for speed". An app, he explained, could still be used to serve users amber warnings - perhaps advising them not to visit an elderly relative or a friend in a vulnerable group - while their contact awaited a result.

"The app provides the best early warning system by enabling us to record close physical contact with people we know, but also those we don't know or can't remember," the Oxford Big Data Institute academic told the BBC.

"Our latest analyses suggest that even at low levels of uptake, the app will have a protective effect across a localised network of contacts - if you, your friends, colleagues and family download the app, you're creating a local alert network within your community."

But it is still not clear whether other parts of the UK will adopt it.

Earlier, Northern Ireland's chief scientific advisor told the Stormont Health Committee that he planned to focus on manual contact tracing, saying he thought the app's usefulness had been overstated.

"At best, it is an adjunct," Prof Ian Young said.

The Health Minister Robin Swann added that he had concerns that the app would be unattractive to users because of concerns about it draining battery life, and that people at the end of a phone were already proving effective.

- Published28 May 2020

- Published26 May 2020

- Published24 April 2020