Tech Tent: Tech and the US election

- Published

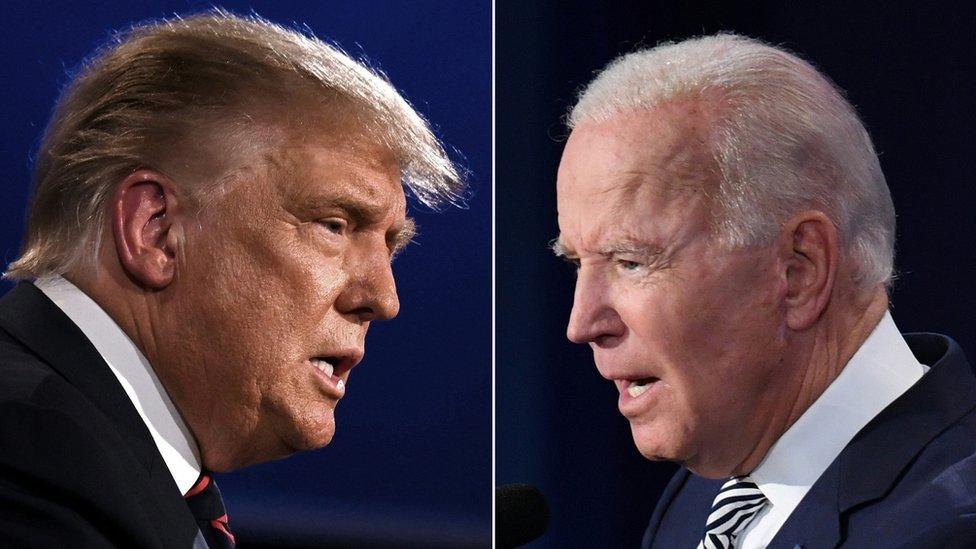

Will a Trump administration or one led by Joe Biden be more likely to break up Google? Will disinformation, spread on Facebook, change the course of the election? And could TikTok be the surprise weapon in the armoury of political campaigners?

In a special edition of Tech Tent, we explore this and other questions about the US election and what's at stake for the technology industry.

On Tuesday, just two weeks before election day, the Trump administration stunned Silicon Valley with its anti-trust lawsuit against Google, the most significant such move since the Department of Justice took on Microsoft in the 1990s.

Last month, it was Democrats on the House Judiciary Committee who issued a report calling for this kind of action against big tech firms - but it was Attorney General William Barr, along with Republican law officers from 11 states, who launched a broadside against Google's alleged anti-competitive practices.

One of the leading experts on competition economics, Prof Fiona Scott Morton of Yale University, tells Tech Tent the mood has shifted against the tech firms on both sides of the political divide.

"I think the good times for Silicon Valley are over," she says. "I think we are headed toward some more oversight and regulation."

She pinpoints two things that have changed: the public has become more aware of the damage caused by social media firms, and politicians have understood that platforms like Google may actually harm local businesses.

"If you are a business, who doesn't have a senator or a congressman who's in the district of Google, you're really anxious for some anti-trust enforcement or some regulation to help protect you from these very large platforms."

Cambridge Analytica

In the short term however, the focus is on whether the social media giants are having a positive or negative impact on the campaign for the White House. In 2016, a few days after Donald Trump's surprise election victory, Tech Tent interviewed David Wilkinson, a young British employee of a data company claiming to have swung it for him.

That business was Cambridge Analytica and two years later, when it emerged that some of its data had been illicitly harvested from Facebook, a huge scandal erupted over the social media giant's role in the election.

But this time the focus is not on the use of data to send micro-targeted ads to voters - it appears that Cambridge Analytica massively overstated its capabilities in that area - but on the use of social media to spread misinformation.

From the QAnon conspiracy theory to disinformation about postal voting, Facebook, Twitter and YouTube have struggled to stem the flow of falsehoods reaching voters, sometimes changing their policies on an almost daily basis.

The BBC's disinformation reporter Marianna Spring tells us that the social media battleground in 2020 is about far more than just buying thousands of targeted ads for different voters.

"When we talk about what influences voters and also what could undermine the democratic process, it is far more complex than simply micro-targeting specific individuals with certain campaign messages. It's about lies and it's about narratives that can change people's entire world view."

TikTok

One platform that was not around in 2016 to play a part in the election was TikTok, the Chinese-owned short video site that President Trump wants to see taken over by an American business.

The BBC's TikTok specialist Sophia Smith-Galer tells us how a site you might have thought was all about lip-syncing to Korean pop has become a campaign tool.

She explains that while political ads are banned on TikTok, campaigners get their message across through so-called Hype Houses. One example is the Republican Girls, a group where like-minded young conservative women can find friends as well as spread their message.

Sophia, who has made a documentary about TikTok's role in the election, says campaigners are learning that it requires different skills from other platforms. "It demands personality, and it demands a sense of comedy, and I don't mean that you have to be funny in all of your videos. But you do need to be relatable," she says.

But here is the big question - does any of this change the hearts and minds of voters? The non-partisan Pew Research Center has been monitoring perceptions of social media and its role in the campaign.

Its research director for technology Lee Rainie tells us that overall, people think it has a very negative effect: "They're weary of the kind of political discourse that they see online. And so they would like political ads banned on social media platforms."

But there is evidence that news and views shared online - whether accurate or not - has an effect. "One in seven social media users says that something they've seen on social media has changed their minds."

In even a moderately close election, changing the minds of one in seven voters could be crucial, so don't expect the politicians to give up on using social media as a key platform for their messages.