NHS Covid-19 app to issue more self-isolate alerts

- Published

- comments

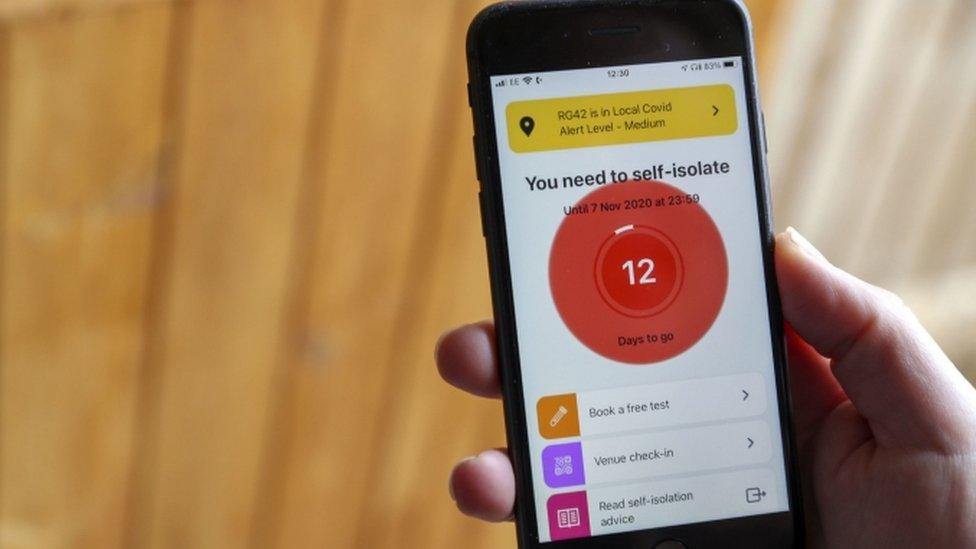

An update to England and Wales' contact-tracing app is set to serve more self-isolation alerts.

Gaby Appleton - who recently took over NHS Covid-19 - said this was being done to help tackle the spread of the coronavirus.

The change coincides with a change to the app's algorithm to make its contact-matches more reliable.

The Health Secretary previously voiced concern about people being told to stay at home because of false alerts.

As a result, the app had required a higher risk score to be calculated before triggering a self-isolate command.

The new director of product for Test and Trace said her team was so confident in the improvements made to distance estimates that it had moved the level at which notifications were triggered even lower than first planned.

"The update to the risk threshold is expected to increase the number of people asked to self-isolate by the app, having been in close contact with someone who tested positive," Gaby Appleton blogged, external.

"We believe lowering the threshold is necessary to reduce the R rate and break the chain of transmission."

One risk is that if people start receiving more alerts they may become less willing to obey them.

Privacy protections built into the software mean officials cannot see who it has told to self-isolate, and users cannot be fined for ignoring the app's guidance.

19 million downloads

Ms Appleton added that the app has proven to be more popular than any other European counterpart, despite having been one of the last to launch.

She said more than 19 million people had downloaded it since 24 September, equating to about 40% of adults with access to a compatible smartphone.

Officials believe the publicity campaign for the app had a good impact

The BBC has learned that the Test and Trace team has gathered further data that indicates the app is out-performing other countries' efforts in terms of how many people have disclosed a positive test to trigger the automated contact-tracing process.

However, it is not ready to publicly disclose the information at this time.

Officials also declined to reveal whether they had logged the number of people who had uninstalled the app, which would give a better indication of the number of active users.

No payments

Version 3.9 of NHS Covid-19 takes advantage of a filtering process called Unscented Kalman Smoother, external, to screen out suspect readings.

The technique can be used for the first time as Apple and Google - which provide the underlying technology behind the app - have made it possible to scrutinise more of the Bluetooth data that is gathered to identify when two users are in close proximity.

In simple terms, the app can now determine when the inferred distance between two handsets has rapidly fluctuated over a short timespan - for example being measured as being 2m, then 10m, then 3m, then 8m - within 15 minutes.

This is not the way people normally interact with each other. However, such errant readings can be caused by Bluetooth signals bouncing off the metal fittings of a train, for example.

The algorithm now takes this into account when calculating its risk score.

Experts from the Alan Turing Institute - who have been helping improve the app - believe it is now close to, or perhaps even more accurate than, the original abandoned effort that did not rely on Apple and Google's framework.

They believe further improvements can still be made.

But the short-term consequence of the upgrade is that they believe the app will be able to confidently identify more high-risk cases, and thus trigger more notifications.

That could prove controversial since users who are on low incomes can claim £500 from their local authority when ordered to self-isolate by a manual contact tracer, but there is no current way to get the payment if instructed to isolate by their handset.

One other benefit of the upgrade is that it should end the problem of "ghost notifications", in which notifications popped up outside the app warning users they had been close to someone who had Covid-19, but the app itself did not recommend any action.

From now on, users should only get such alerts for "high-risk" encounters that they need to act on.

By one important measure, the number of downloads, the NHS Covid-19 app can be said to be a big success - even if it is hard to verify the claim that it's outpaced other European apps.

The work done by experts from the Alan Turing Institute to improve the way it uses Bluetooth to measure one phone's proximity to another is also an impressive achievement, and one acknowledged by other technologists working in this field.

But one question remains unanswered - does this or indeed any other contact-tracing app work in stopping the chain of infection?

The anonymous nature of the Apple-Google toolkit, which is the foundation of the app, makes it hard to know much about how it is working. But the teams behind the Scottish and Northern Irish apps have released some data.

The Scottish government says more than 10,000 people have been contacted via the Protect Scotland app to let them know they have been in close contact with someone who has tested positive for Covid-19.

WATCH: How to install the NHS Covid-19 app

In Northern Ireland, more than 16,000 people have received notifications to self isolate after nearly 5,000 positive test results were entered into their app.

The Department of Health says it wants to be absolutely sure that its data about the NHS Covid-19 app is accurate before releasing it.

That is frustrating some on the app team, who say they have a good story to tell about the number of alerts being sent out. That number - whatever it is - will increase following the tweaking of the algorithms, which determine what is a risky contact.

With reports from Ireland and Germany that their previously successful manual contact-tracing operations are struggling to cope, apps which automate the process may become more important.

But a report in the Times says no data is being collected from the manual, external NHS Test and Trace service about how many people comply with orders to self-isolate.

With a privacy-focused app such data will never be available - after all, if you don't even know the identity of the people receiving alerts you can hardly check up on them.

- Published28 October 2020