Christmas shopping: Why bots will beat you to in-demand gifts

- Published

- comments

Black Friday is over, and the Christmas shopping rush is here. But any great deals on a new games console or hot-ticket piece of electronics will probably be snapped up by an army of bots working for those looking to make a profit.

Bots are constantly-running software programs that have hit online retail for years. But the pandemic means higher demand for lots of items, and many more people shopping online.

What's the bot problem?

Retail bots scan the pages of websites around the world for the exact second an item goes on sale - and alert their owners so they can beat the crowd. Some automatically buy it, faster than any human can.

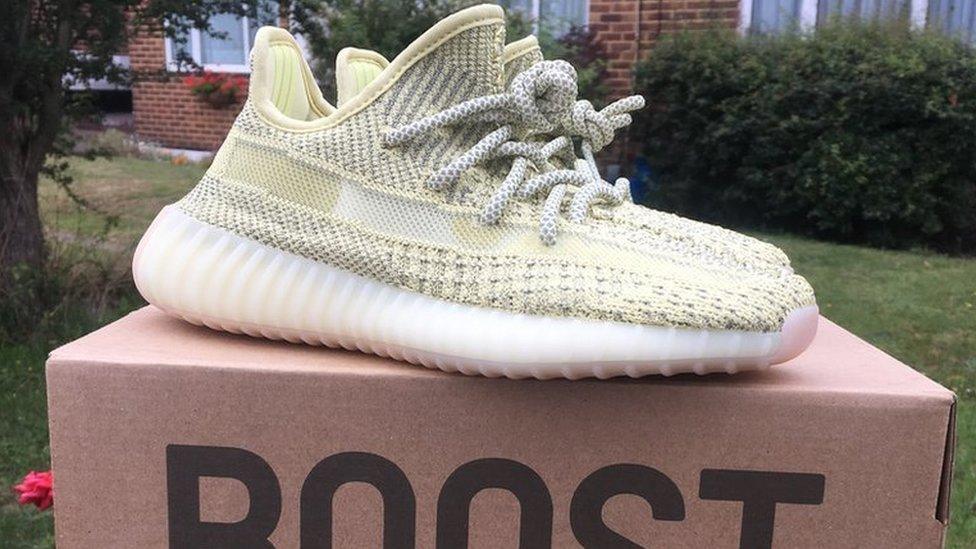

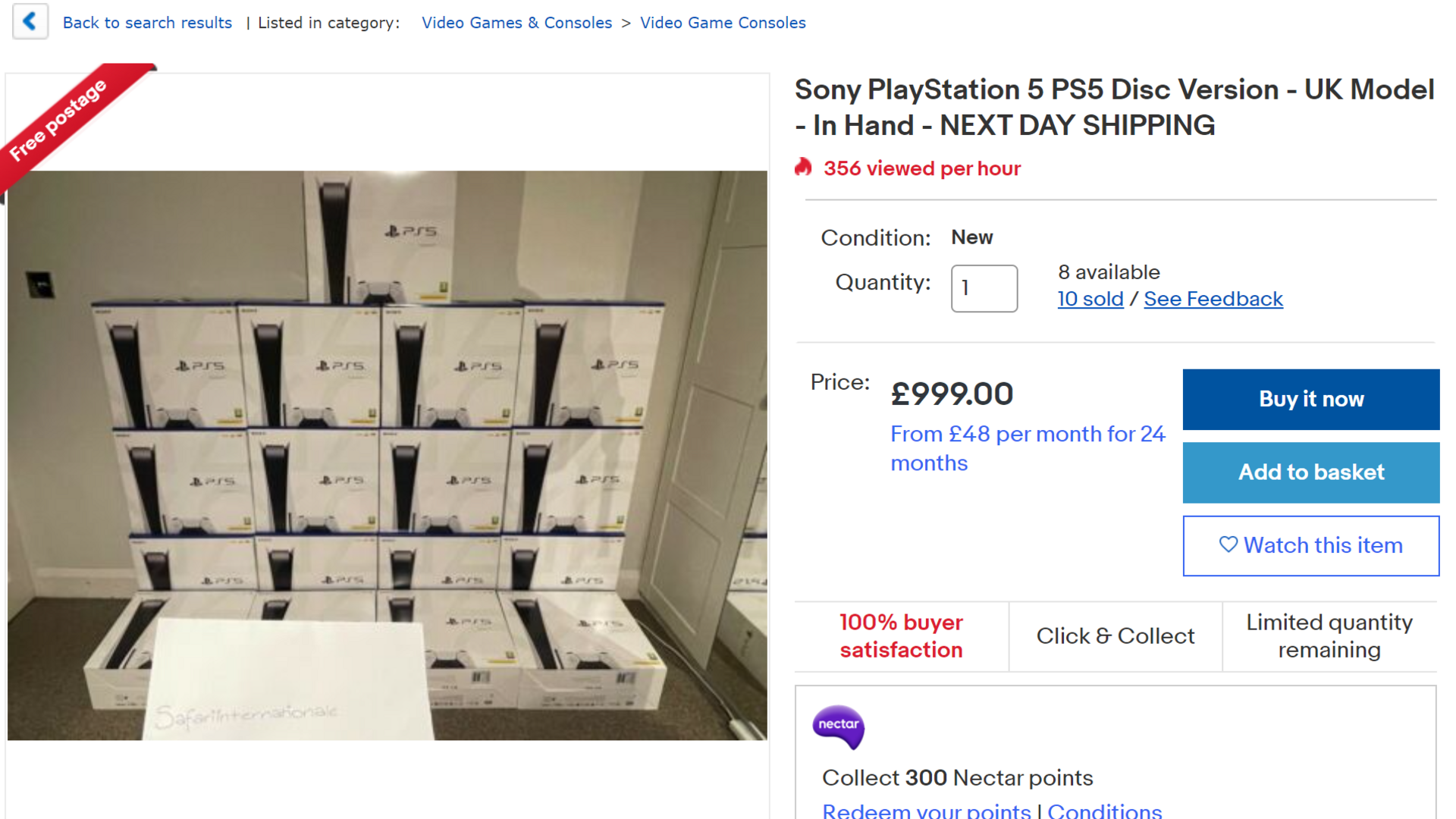

That's how the out-of-stock PlayStation 5 is available on eBay for hundreds of pounds more than its asking price, and why the Xbox Series X cropped up online for £5,000.

The £449 version of the PlayStation 5 is being sold online for £999

And that's just "the tip of the iceberg", says Thomas Platt, from the bot management firm Netacea.

Everything from cuddly toys to film collectibles are seeing bots snap up the stock, he reports.

If there's a "niche audience" or high-profile launch, "those industries are being targeted", he adds.

How bad is it?

The pandemic caused supply chain issues earlier this year, physical stores are shut, everything is online - it's a "melting pot of factors", Mr Platt says.

"On top of that... the bots are really becoming readily available, easy to use."

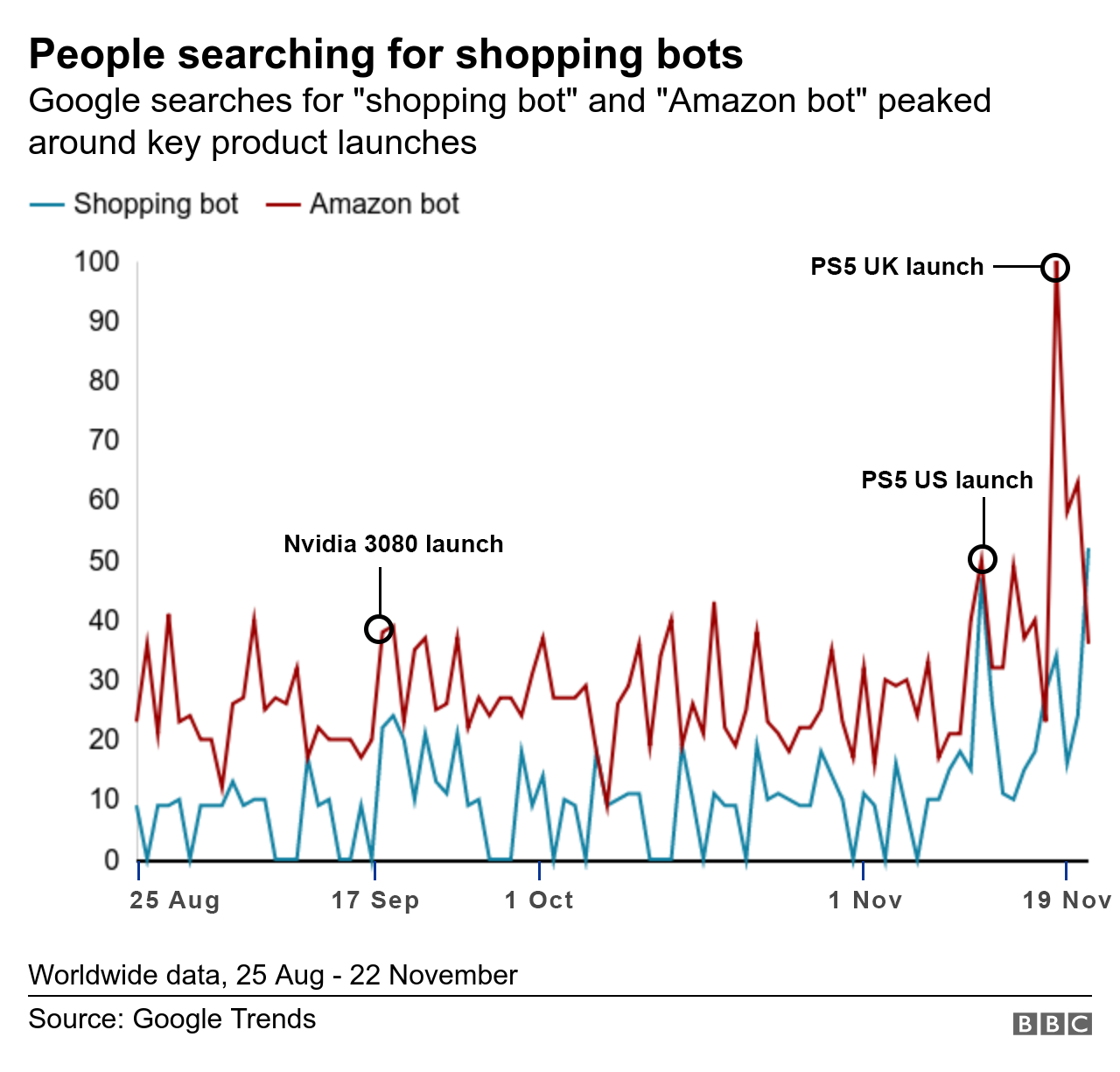

The launch of Nvidia's PC gaming graphics card, the 3080, was "probably the most extreme case of what bots can do", says one of the moderators from r/BuildaPCSalesUK, external - a group of bargain hunters who help each other find PC parts.

"Less than a second after launch, all stock sold out," they explain.

"Users on retail websites didn't see a 'buy now' button, but rather a 'sold out' button, as all the stock had immediately been sniped by bots, with a sprinkling of the odd lucky person in there."

Rob Burke, former director of international e-commerce for major international retailer GameStop, says bots have always been a problem.

"At times, more than 60% of our traffic - across hundreds of millions of visitors a day - was bots or scrapers. Especially in the run-up to big launches."

And that creates a bit of an ethical dilemma for the shops.

"On the one hand, you just want to shift the product so who cares if it's a bot or a 'real' customer?" he says.

"On the flip side, if none - or very few - of your real customers can get the product with you, they will naturally go elsewhere."

How do they work?

So-called "sniping" bots issue alerts to users when an item comes back in stock - letting its owner buy it before anyone else.

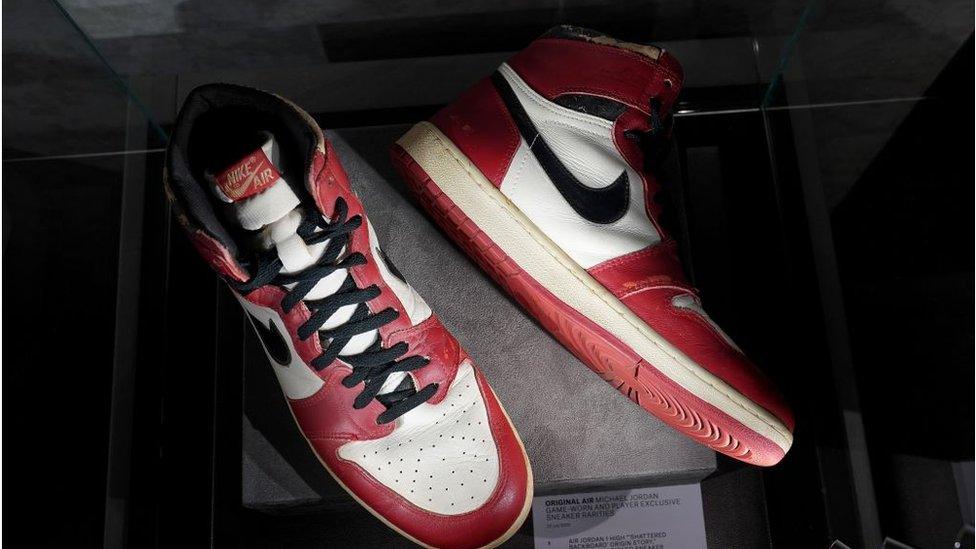

But the most advanced bots are all-in-one solutions that spot the deal and automatically check-out. They often come from an unusual place: the limited-edition training shoes market.

Trainers (or sneakers) have been a hotbed for limited, high-demand releases for years, with people queuing outside shops to buy them - or trying to nab them online. That has led to the development of advanced bots - ones that are now being turned to other purposes.

So-called "cook groups" live in private chat channels on apps such as Discord, swapping tips on who will be stocking what, rumoured release times, and trying to find the store pages before they're officially on sale. Bot owners use this info to tune their attacks.

Mr Platt says he knows of one extreme example where a group rented a server located physically closer to the target website's server - giving them a split-second advantage on the time it takes for web traffic to flow.

Why? Because the scalpers are in competition with each other as much as regular buyers.

Examples of success posted by members of one "exclusive" group called Bounce Alerts

Membership of those elite groups can cost from tens to hundreds of dollars.

"There's definitely an element of exclusivity at the more sophisticated end of the market," Mr Platt says.

"There are bots on sale that can cost thousands... some of the bots have become so expensive, and so limited, that you rent them now."

That means that some people who are genuinely after an item are renting a bot to make sure they get it, or just "employing" a botter to buy it for them.

It's becoming big business. The trainers resale market alone is valued at about $2bn, external and growing by 20% a year, according to US consultancy Cowen.

What does it mean for Christmas shopping?

All of this means that in-demand items are harder than ever to source - especially if there's a good deal.

And then there's arbitrage: buying items low and selling high, exploiting the price difference between markets. Bots help that happen on an automated, commercial scale.

"You can take all those items, if you know in two weeks' time [when] the sales are gone you can sell them at double the price," Mr Platt explains.

There is a silver lining to the proliferation of bots around major sales days such as Black Friday: they can lead to lower prices in some cases.

That's because scraper bots - the type that check prices but don't buy anything - are actually used by the retailers themselves.

Many of the biggest retailers scan each others' websites, making sure they're not beaten on the best deal in the sales.

What can be done about it?

Many retailers declined to discuss their defences, while bot-sellers ignored requests for interviews.

Technically, there's nothing illegal about the practice. The UK banned the use of such bots for ticket sales, but in other retail sectors it's not explicitly against the law.

However, retailers are coming up with smart workarounds.

Currys PC World confused many of its customers when the PS5 and Xbox Series X went on sale - they listed it at £2,000 more than they should have been, external. Real customers with pre-orders were sent a discount code for £2005, which had to be manually entered, bringing it back down to real levels (minus the £5 pre-order deposit).

Some retailers are charging people's bank cards the full price of the item for a place in the queue. Others are combing through order lists and cancelling suspicious ones - for example, if one address is getting a dozen of the same item.

Related topics

- Published17 November 2020

- Published5 January 2020

- Published13 August 2020

- Attribution

- Published17 September 2020

- Published14 January 2020