Google fired employees for union activity, says US agency

- Published

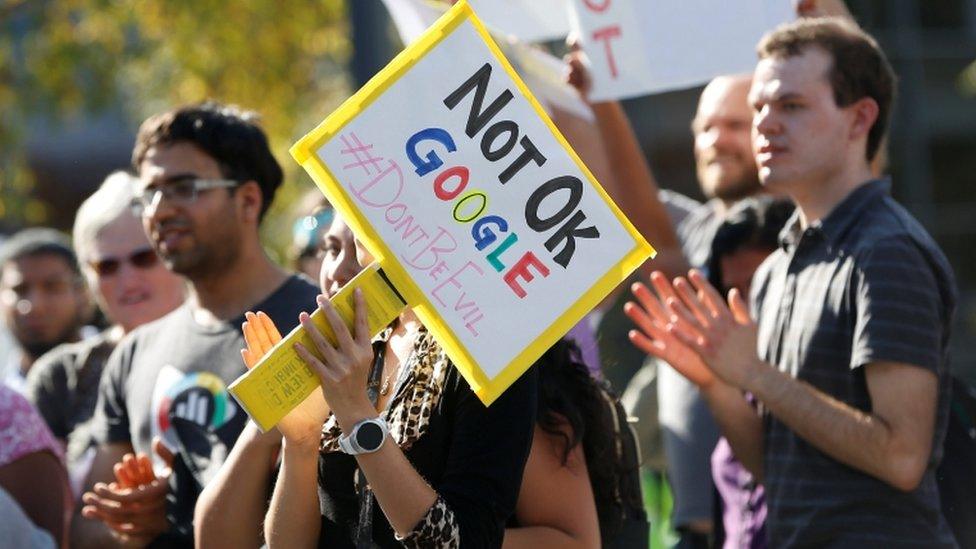

Google employees stage a walkout in November 2018 over sexual misconduct allegations

Google unlawfully fired employees for attempting to organise a union, a US federal agency has said.

A complaint filed by the US National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) alleged that Google unlawfully monitored and questioned its employees about their union activity.

It fired a number of staff for violating data security - but the NLRB said the rules were applied only to those engaging in union activity.

Google denies doing anything unlawful.

It comes as another prominent Google employee, a leading figure in AI ethics, said she was fired for an email she sent to employees.

Why were they fired?

The NLRB complaint dealt with employees who were fired over a year ago, in November 2019.

Known as the "Thanksgiving Four", they were officially fired for breaking security and safety rules. But the workers alleged they were fired for "speaking out" about Google's policies.

Reacting to the NLRB complaint, Google said it had "always worked to support a culture of internal discussion".

"Actions undertaken by the employees at issue were a serious violation of our policies and an unacceptable breach of a trusted responsibility," it said.

But the NLRB said the rules in question were only applied to those employees who were engaged in worker organisation.

What did Google do?

The complaint, on behalf of two of the workers, said the employees accessed basic tools like employee calendars and meeting rooms for the purposes of organising union-related activities.

Google "interrogated" its employees about accessing such information, which the NLRB said were protected activities under labour organising rules.

It also "threatened employees with unspecified reprisals" and demanded they address any workplace concerns through official channels only.

And it also accessed an employee slide presentation that was part of a union drive, the complaint said.

In November 2019, Google brought in rules banning employees from accessing each others' calendars other than for reasons directly related to work.

It did so "to discourage its employees from forming, joining, assisting a union or engaging in other protected, concerted activities", the NLRB said.

The company fired the workers behind the activity "to discourage employees" from doing the same, it added.

All of these actions amounted to "interfering with, restraining, and coercing employees" when it came to their rights.

Google has been given two weeks to respond to the NLRB complaint. A hearing will be held in April.

Laurence Berland, one of the employees named in the complaint, said: "Employees who speak out on ethical issues, harassment, discrimination and all these matters are no longer really welcome at Google in the way they used to be."

"I think it is part of a shift in culture there."

What happened to the AI ethics researcher?

The NLRB news comes on the day that a well-respected member of Google's AI team, Timnit Gebru, said she had been fired by Google.

She tweeted, external that she was fired "for my email to [internal Google group] Brain Women and Allies".

She wrote that her corporate email had been deactivated, and so she could not share a copy of the email - but that Google told her that "certain aspects of the email you sent last night to non-management employees in the brain group reflect behaviour that is inconsistent with the expectations of a Google manager".

She also said the company said it accepted her resignation - which she said she had never offered.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

The news prompted a backlash among software engineers and AI ethics watchers, among whom Ms Gebru is a respected researcher.

She was one of the authors of a 2018 paper, external which concluded that AI facial recognition has difficulty identifying dark-skinned women - because the original datasets are mostly based on white men.

Earlier this year, she was interviewed in a piece for The New York Times titled A Case for Banning Facial Recognition, external and why she believes it should not be used for policing.

"The combination of over-reliance on technology, misuse and lack of transparency - we don't know how widespread the use of this software is - is dangerous," she told the newspaper.

Related topics

- Published26 November 2019

- Published8 May 2020

- Published11 March 2020

- Published1 November 2018

- Published13 September 2019