Covid-19: NHS app has told 1.7 million to self-isolate

- Published

- comments

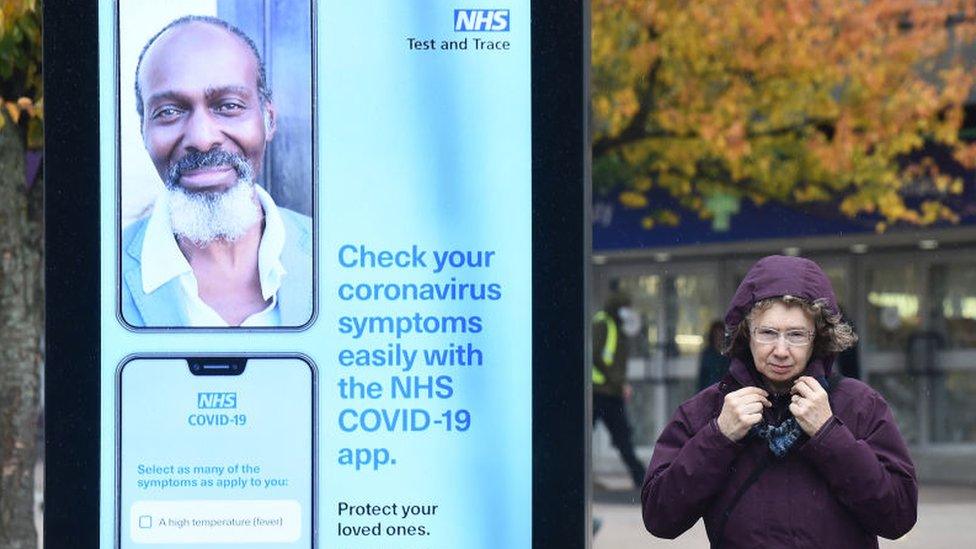

Approaching two million people have been told to self-isolate by the app

The NHS Covid-19 app has told 1.7 million people in England and Wales to self-isolate to date.

Health ministers have also revealed they believe it has prevented about 600,000 cases of the disease.

In a further disclosure, internal data indicates that about 16.5 million people are currently actively using its contact-tracing tool.

That figure is 24% below the app's latest download tally, which is the government's preferred measure.

The discrepancy is likely to be down to people uninstalling the app, turning off its contact-tracing capabilities, or simply failing to have activated it in the first place.

Each handset actively taking part sends a digital "heartbeat" once a day to the Amazon computer server involved, allowing the current usage figure to be calculated.

And while the number of total downloads has slowly grown from 20.2 million, external to 21.7 million over the past two months,, external the number of phones pinging the server has been more or less flat.

Risking lives

This represents the first detailed data released about the app's use since it was made widely available to people in England and Wales in September.

Scotland, Northern Ireland, Jersey and Gibraltar have their own separate apps.

Baroness Dido Harding, executive chair of the NHS Test and Trace programme, had been under pressure to release the figures for months, and the BBC unsuccessfully attempted to obtain some of the figures via a Freedom of Information request in November.

The app could reduce the number of infections once lockdowns end and people spend more time outside their homes

The intention in releasing the data now is to reassure the public that the app can save lives, and in doing so encourage more people to both install it and follow its advice ahead of lockdowns being eased.

"People who are not following the app's instructions are risking themselves and their colleagues and their families," Baroness Harding told the BBC.

"The more you follow the instructions of the app, the fewer outbreaks you'll have in your workplace and the safer it will be."

A spokeswoman added that these instructions include circumstances in which it is recommended to pause the contact-tracing function., external

Anonymised findings

The app uses Bluetooth logs to retrospectively warn users if they were at high risk of contagion from someone infected with the virus, who was recently in their vicinity.

Alerts can be served within 15 minutes of an infected person approving use of their positive test result. But the system's decentralised nature means neither the person who triggered the warning, nor the authorities, can identify who receives the notifications.

Some anonymised data is, however, collected.

For the first time, it has been revealed that:

1.4 million people have reported symptoms into the app. The software may order users to stay at home as a result, but does not cascade alerts to others

825,388 people have entered a positive test result into the app. This has led to more than 1.7 million people receiving self-isolate alerts

an average of 4.4 self-isolate alerts are triggered for every app user who tests positive and uses its contact-tracing function. Some people will receive multiple notifcations

the app's QR barcode-based venue check-in feature has been used more than 103 million times

253 venues have been determined to be at risk as a consequence of the QR code facility since 10 December, triggering alerts to visitors to monitor their symptoms

Restaurants are among venues each to have been given a unique QR barcode

Tier-driven data

Scientists from The Alan Turing Institute and Oxford University worked to provide further analysis of the app's impact

They estimate that 594,000 cases have been averted because of the technology.

And they forecast that for every additional 1% of the population that uses the app, the number of Covid cases should fall by 2.3%, external.

The academics have benefited from the fact that the app was retooled in October to take account of the tier system introduced at the time in England, which operated on a local authority basis.

This allowed anonymised usage data to be compared between two neighbouring council areas where the spread of the pandemic was similar, but uptake of the app differed.

The researchers took account of other factors - including poverty levels - to calculate the degree to which suppression of the virus's spread could be linked to the app.

However, they acknowledge that they cannot be certain that usage of the app caused all of the effects being attributed to it. And while they are publishing their work, it has yet to be peer-reviewed.

Even so, the firm involved in developing the app said confidence was growing that it is indeed making a difference.

"The data suggests that we have made a dent in the overall infection rate," Wolfgang Emmerich, chief executive of Zuhlke UK, told the BBC.

"What we really have to do now, particularly as we're preparing to come out of lockdown, is to drive that adoption rate back up and to get people to switch [the app] back on again."

Mr Emmerich also revealed that his team had put plans to extend the app to older iPhone models on the back burner, in order to prioritise other new features, but declined to say what they are.

Covid symptoms: What are they and how long should I self-isolate for?

Soon after the NHS Covid-19 app was launched last September, we learned one important piece of data - that over 20 million people had downloaded it.

That was a pretty good result compared with take-up of similar apps elsewhere, but what we didn't know until now was something far more important - did it work?

Now these figures do appear to show that plenty of people have been pinged by the app and sent into isolation.

More impressively, research appears to show that in areas where take-up of the app was high, the infection spread more slowly than in places where it was lower.

But other scientists will want to drill down for themselves into whether other factors were at play in the link between high take-up and low infection rates.

Plus the private nature of the app means there are some key questions that can't be answered:

how many people obeyed the ping on their phone telling them to self-isolate?

how many of them had been separately contacted by the manual track and trace operation anyway?

how many of those alerts were false positives or negatives, meaning people who were not at risk were told to self-isolate while the reverse was true of others?

how many people have grown bored with the app and switched off Bluetooth or uninstalled it?

Still, using a Bluetooth app to trace people who might be infected with Covid-19 was always an experiment with an untested technology.

And the scientists who have been working on this project for many months now feel they've proved that it has made a significant contribution to the fight against the virus.

- Published1 February 2021

- Published14 January 2021

- Published13 January 2021

- Published15 December 2020