Met Office and Microsoft to build climate supercomputer

- Published

- comments

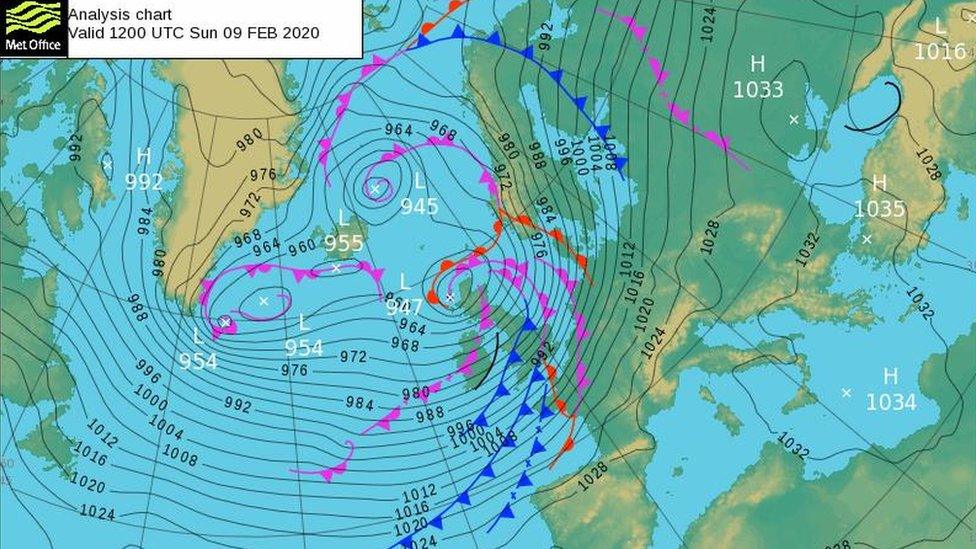

The Met Office's existing supercomputer

The Met Office is working with Microsoft to build a weather forecasting supercomputer in the UK.

They say it will provide more accurate weather forecasting and a better understanding of climate change.

The UK government said, external in February 2020 it would invest £1.2bn in the project.

It is expected to be one of the top 25 supercomputers in the world when it is up and running in the summer of 2022. Microsoft plans to update it over the next decade as computing improves.

"This partnership is an impressive public investment in the basic and applied sciences of weather and climate," said Morgan O'Neill, assistant professor at Stanford University, who is independent of the project.

"Such a major investment in a state-of-the-art weather and climate prediction system by the UK is great news globally, and I look forward to the scientific advances that will follow."

The Met Office said the technology would increase their understanding of the weather - and will allow people to better plan activities, prepare for inclement weather and get a better understanding of climate change.

The supercomputer will be able to:

provide more detailed weather models

run more potential weather scenarios

improve localised forecasts

better predict severe weather

The new supercomputer will be six times more capable than the current one

"Working together we will provide the highest quality weather and climate datasets and ever more accurate forecasts that enable decisions to allow people to stay safe and thrive," said Penny Endersby, chief executive of the Met Office.

Microsoft UK chief executive Clare Barclay said the supercomputer would help the UK remain at the forefront of climate science.

Supercomputing

The exact location for the new computer was not revealed; however, the Met Office said it would be in the south of the UK. It will use Microsoft Azure's cloud computing services and integrate Hewlett Packard Enterprise (HPE) Cray supercomputers.

It will run on 100% renewable energy and will have more than 1.5 million processor cores and more than 60 petaflops - or 60 quadrillion (60,000,000,000,000,000) calculations per second.

That will, in theory, allow it to handle more data, more rapidly, and run it through simulations of the atmosphere more accurately.

Cody Godwin is a reporter based in San Francisco. For more news, follow her on Twitter at @MsCodyGodwin, external

Related topics

- Published9 April 2021

- Published17 February 2020

- Published18 May 2020