'I was terrible at crosswords so I built an AI to do them'

- Published

Matt Ginsberg was so bad at crosswords he had to build a machine that could make him look better

Matt Ginsberg is good at a lot of things - he is an AI scientist, author, playwright, magician and stunt plane pilot. But he isn't very good at crosswords.

In fact, despite writing them for the New York Times, he says that when they are published, he often cannot solve his own.

So when he was sitting in a hotel ballroom losing yet again in a major US crossword competition, he decided to do something about it.

"I was with 700 people who were really good at solving crossword puzzles and it annoyed me that I was so terrible, so I decided to write a computer program that would get even on my behalf," he told the BBC.

And finally he did. After 10 failed attempts, Dr Fill - as the program is known - has just won its first competition.

It came first in the American Crossword Puzzle Tournament, the leading crossword competition in the US.

Dr Fill was trained on a mass of data, including a giant database of crossword clues and answers scraped from the web.

It was taught to search at speed through possible placements of words in a crossword grid. It was, admits Dr Ginsberg, quite a "primitive" system.

This year, he had some help.

"A few weeks before the event, I was contacted by people working at Berkeley who had built a crossword clue answering system. We realised pretty quickly that we could combine the two."

Prof Dan Klein, who heads the Natural Language Processing Group at Berkeley College, University of California, explained to the BBC that he was looking for something to bring the team together during lockdown - and they came up with the idea of building a crossword solver.

When he heard about Dr Fill, he thought the two systems would make a good partnership.

Crossword puzzles can fool the smartest of humans, so how would a machine fare?

"Our system brought a broader understanding of language, and Dr Fill was good at how the answers combine with other clues. They are very different techniques but they spoke a common language of probabilities."

Poisoned Penne

Crosswords may seem like a strange thing to task AI with solving but in fact they represent a very fertile playground for machine learning.

Basic crosswords that simply require someone to know the answer to the prompt are extremely easy for an AI, which will have been programmed with vast amounts of information from the web from sources such as Wikipedia.

Cryptic crosswords, which a UK audience might be more familiar with, are actually also quite easy for a machine, because they contain very set rules and pointers to things such as anagrams.

American-style crosswords, on the other hand, require both knowledge and a degree of lateral thinking.

One question that Prof Klein is particularly proud that Dr Fill got right was: "Pasta dish at the centre of a murder mystery."

The answer was poisoned penne. "That wasn't to be found on Wikipedia," said Prof Klein.

Dr Ginsberg agrees that American-style crosswords can be "brutally hard" for computers to figure out.

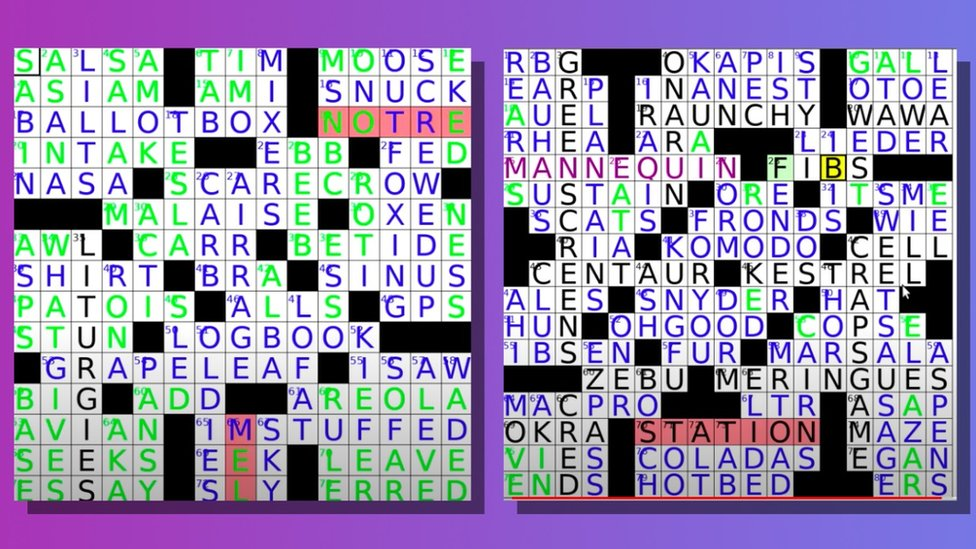

Dr Fill only made three mistakes in the whole competition, although in the end only won by a small margin.

Some examples of the puzzles the AI tackled in the competition

Dr Ginsberg didn't get the $3,000 (£2,100) prize money, something he said was agreed beforehand and was "the right decision".

He acknowledged that it is tricky for organisers of competitions, if both humans and machines are taking part.

Luckily, he said, the crossword community is a "wonderful bunch".

While the competitors may pretend to hate its AI rival - booing Dr Fill when it does well and cheering if it does badly - at heart he believe the contestants were "really rooting for me".

He doesn't know that for sure, as this year's event was virtual - which meant he couldn't see any of the competitors.

It did mean though that Dr Fill was able to benefit from extra computer power, which wouldn't normally have been transportable.

The achievement won praise from DeepMind, a leading AI research firm and one that is not unaccustomed to winning games - most notably beating a world-class Go player in 2016.

Michael Bowling, senior research scientist at DeepMind and professor of computing science at the University of Alberta, said of the win: "Congratulations to Dr Ginsberg and the Berkeley team. It's a terrific achievement and an inspiring collaboration, both seeing leading AI researchers combining forces, and seeing powerful AI building blocks of search and learning being employed together.

"Knowing there's another one better at crosswords than me won't change my enjoyment struggling over a Tuesday puzzle."

Learning differently

The move towards what is known as general purpose AI, where a machine can complete a series of tasks rather than just being good at one thing, is currently a long way off, but much progress has already been made.

Natural Language Processing - Prof Klein's specialism - has already notched up achievements in real-world scenarios as diverse as translation, speech recognition and enabling the daily conversations we have with voice assistants.

But, said Prof Klein, we are only just at the beginning of our understanding about how machines learn.

"Our understanding of what is easy and what is hard for computers is a moving target. People used to be amazed that a computer could compete at chess, but now we think it is amazing that a human can compete against a machine at chess."

The way a computer decides which move to make in that game is a combination of "maths, logic, and looking ahead" which is unlikely to be exactly the same way a human would consider the same move, he said.

Dr Ginsberg agrees that humans and machines approach problems from different perspectives.

"Dr Fill solves these puzzles very differently to how we do. It is doing a giant search of all possible answers."

That diversity is, he said, a "good harbinger" for the future.

"We will solve more problems with them at our side than we can by ourselves. We are going to team up with machines to our mutual benefit."

But he has no plans for world domination, just yet.

"Dr Fill is just a crossword program and I am fine with that."

Related topics

- Published25 February 2021

- Published14 April 2021