Spy bosses warn of cyber-attacks on smart cities

- Published

- comments

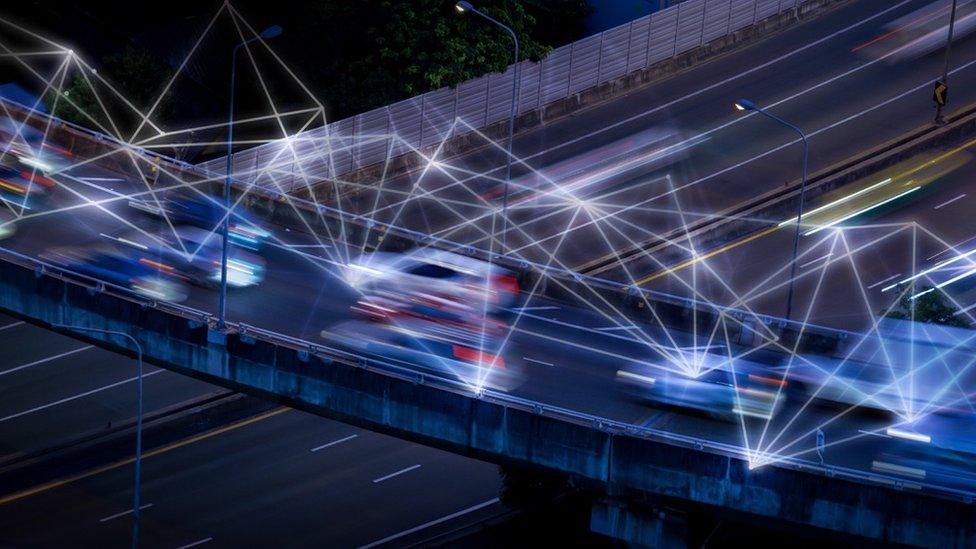

Cities are increasingly relying on sensors and other network-connected devices which feed data into a central system

Smart cities will be a target for hackers, and councils need to be prepared, the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) has warned.

Sensors and internet-connected devices may improve urban services, but could also be used by hackers and foreign states to disrupt or spy.

The NCSC - an arm of GCHQ - has published guidance, external for local authorities on how to secure what they call "connected places".

They warn that critical public services will need to be protected from disruption.

Sensitive data also needs to be secured from being stolen in large volumes.

Smart cities and connected rural environments promise a host of benefits. Sensors will monitor pollution or offer real-time information on parking. Cameras will track congestion and manage traffic flow.

This should help improve efficiency, and help local authorities become more sustainable.

Italian Job

But the growing dependency on technology also brings risks. The NCSC is warning of possible "destructive impacts" if systems were switched off which, in some cases, could even "endanger" residents.

Another concern is that the large volumes of data about people that are collected could erode privacy by allowing citizens to be tracked even more, or could be stolen by criminals or hostile states.

With cars more connected to each other and to traffic infrastructure, there is a danger of hackers causing gridlock

The NCSC's technical director, Dr Ian Levy, claims that one of the first Hollywood depictions of a cyber-attack was against critical infrastructure.

He points not to a recent James Bond film but the 1969 classic 'The Italian Job' in which a computer professor (played by Benny Hill) switches magnetic storage tapes running traffic in the Italian city of Turin, in order to create gridlock which allows a haul of gold to be stolen.

"A similar 'gridlock' attack on a 21st century city would have catastrophic impacts on the people who live and work there, and criminals wouldn't likely need physical access to the traffic control system to do it," Dr Levy warns in a blog., external

"These connected physical environments are just emerging in the UK, so now is the time to make sure we're designing and building them properly," Dr Levy writes.

The new principles advise local authorities on how to design and manage their systems to protect data and ensure they are resilient.

They do not explicitly name any countries or groups likely to carry out an attack. But they do warn about the risks in the context of suppliers of the technology.

China has been at the leading edge of developing smart cities technology, deploying it within its own borders, but also exporting equipment to other countries.

"Some countries seek to obtain sensitive commercial and personal data from overseas, including from the UK," the guidance warns.

"They may also seek the potential to cause disruption to overseas services.

"Suppliers that are part of corporate groups based in these countries may be subject to influence from those governments to access and exfiltrate data from UK-connected places, in support of those countries' security and intelligence services.

"Such suppliers may also be used as a vector for an attempt to take down an essential service," the guidance warns.

The head of GCHQ, Jeremy Fleming, highlighted the risks last month when he warned that the West faced a moment of reckoning when it came to China, and a battle over what values would be embedded in technology.

"If we don't control the technology, if we don't understand the security required to implement those effectively, then we'll end up with an environment or technology ecosystem where the data is not only used to navigate, but it could be used to track us," he told the BBC.