Big Tech must deal with disinformation or face fines, says EU

- Published

Large tech companies, such as Google and Meta, will have to take action on deepfakes and fake accounts - or risk facing huge fines.

Deepfakes are videos using a person's likeness to portray them doing something they never did.

New EU regulation, supported by the Digital Services Act (DSA), will demand tech firms deal with these forms of disinformation on their platforms.

Firms may be fined up to 6% of their global turnover if they do not comply.

The strengthened code, external aims to prevent profiting from disinformation and fake news on their platforms, as well as increasing transparency around political advertising and curbing the spread of 'new malicious behaviours' such as bots, fake accounts and deepfakes.

Clubhouse, Google, Meta, TikTok, Twitter and Twitch are among the 33 signatories to the enhanced code and worked together to agree the new rules .

Firms who have signed up to the code will be compelled to share more information with the EU - with all signatories required to provide initial reports on their implementation of the code by the start of 2023.

Platforms with more than 45 million monthly active users in the EU will have to report to the Commission every six months.

Nick Clegg, Meta's president of global affairs, wrote on Twitter, external: "Combating the spread of misinfo is a complex and evolving societal issue".

"We continue to invest heavily in teams and technology, and we look forward to more collaboration to address it together."

A Twitter spokesperson said the company welcomed the updated code.

"Through and beyond the Code, Twitter remains committed to tackling misinformation and disinformation as we continue to evaluate and evolve our approach in this ever-changing environment," a statement said.

Google did not respond to a request for comment.

What are the dangers of deepfakes?

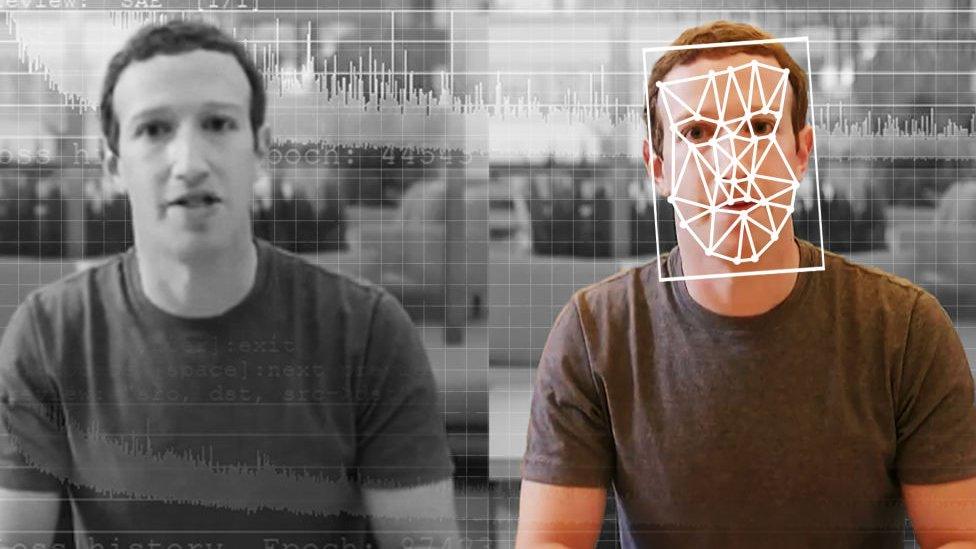

WATCH: The face-swapping software explained

Deepfakes have been identified as an emerging form of disinformation when used maliciously to target politicians, celebrities and everyday citizens.

In recent years they have become increasingly associated with pornography, with faces of individuals mapped onto explicit sexual material.

Deepfakes expert Nina Schick says non-consensual pornographic deepfakes are the primary form of malicious deepfakery today - notably affecting well-known figures including Michelle Obama, Natalie Portman and Emma Watson.

Concerns have also been raised about the use of deepfakes in political sphere, with fake videos of world leaders being shared online during the Russia-Ukraine war.

"This new anti-disinformation Code comes at a time when Russia is weaponising disinformation as part of its military aggression against Ukraine," said Věra Jourová, European Commission vice-president for values and transparency, "but also when we see attacks on democracy more broadly."

"We now have very significant commitments to reduce the impact of disinformation online, and much more robust tools to measure how these are implemented across the EU in all countries and in all its languages."

'Double-edged sword'

The difficulty of telling deepfakes and real footage apart is likely to grow in coming years, says Ms Schick, citing the increased availability of tools and apps needed to develop malicious deepfakes.

While deepfakes allow troublemakers to directly spread disinformation, their appearance more widely on online platforms is causing a climate of information uncertainty - which is open to further manipulation.

For example, genuine footage could be dismissed as deepfakes by those seeking to avoid accountability.

This makes the challenge for citizens to recognise genuine content, and for regulators and platforms to take action on them, ever more difficult.

"You have this kind of double-edged sword - anything can be faked and everything can be denied," Ms Schick says.

A comparison of an original and deepfake video of Meta chief executive Mark Zuckerberg

In recent years, Big Tech companies have made efforts to detect and counter deepfakes on their platforms - with Meta and Microsoft among stakeholders launching the Deepfake Detection Challenge, external for AI researchers in 2019.

But platforms "too often use deepfakes as a fig leaf to cover for the fact that they are not doing enough on existing forms of disinformation", Ms Schick says.

"They aren't the most prevalent or malicious forms of disinformation; we have so many existing forms of disinformation that are already doing more harm."

Under the revised EU code, accounts taking part in co-ordinated inauthentic behaviour, generating fake engagement, impersonation and bot-driven amplification will also need to be periodically reviewed by relevant tech firms.

But Ms Schick adds deepfakes still have the potential to become "the most potent form of disinformation" online.

"This technology will become more and more prevalent relatively quickly, so we need to be on the front foot," she says.

Vlops and Vloses

The DSA - agreed by the European Parliament and EU member states in April - is the EU's planned regulation for illegal content, goods and services online, based on the principle that things which are illegal offline should also be illegal online.

Expected to come into force in 2024, the DSA will apply to all online services that operate in the EU, but with particular focus on what it calls Vlops (very large online platforms, such as Facebook and YouTube) and Vloses (very large online search engines, such as Google) - defined as services that have more than 45m users in the EU.

It will be the legal tool used to support the new code of practice on disinformation, in a bid to tackle fake news and falsified imagery online.

- Published17 October 2019

- Published21 January 2022