Robots to do 39% of domestic chores by 2033, say experts

- Published

Within a decade, around 39% of the time spent on housework and caring for loved ones could be automated, experts say.

Researchers from the UK and Japan asked 65 artificial intelligence (AI) experts to predict the amount of automation in common household tasks in 10 years.

Experts predicted grocery shopping was likely to see the most automation, while caring for the young or old was the least likely to be impacted by AI.

The research is published in the journal PLOS ONE, external.

Researchers from the University of Oxford and Japan's Ochanomizu University wanted to know what impact robots might have on unpaid domestic work: "If robots will take our jobs, will they at least also take out the trash for us?", they asked.

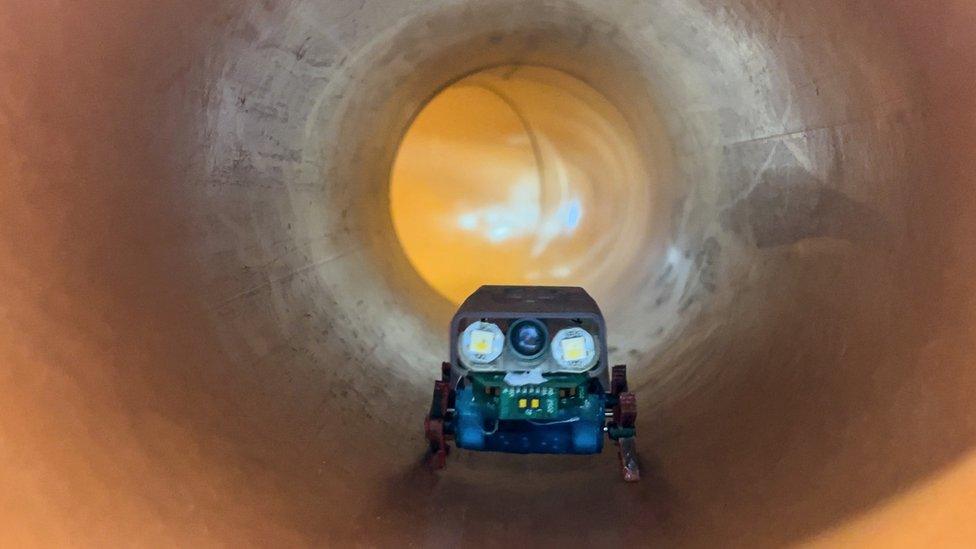

Robots "for domestic household tasks", such as robot vacuum cleaners "have become the most widely produced and sold robots in the world" the researchers observed.

The team asked 29 AI experts from the UK and 36 AI experts from Japan for their forecasts on robots in the home.

Researchers found that male UK experts tended to be more optimistic about domestic automation compared with their female counterparts, a situation reversed in Japan.

But the tasks which experts thought automation could do varied: "Only 28% of care work, including activities such as teaching your child, accompanying your child, or taking care of an older family member, is predicted to be automated", said Dr Lulu Shi, postdoctoral researcher, Oxford Internet Institute,

On the other hand, technology was expected to cut 60% of the time we spend on grocery shopping, experts said.

But predictions that "in the next ten years" robots will free us from domestic chores have a long history and some scepticism may be warranted. In 1966, TV show Tomorrow's World reported on a household robot which could cook dinner, walk the dog, mind the baby, do the shopping, mix a cocktail and many other tasks.

If its creators were only given £1m the device could be working by 1976, ran the news story...

Allow YouTube content?

This article contains content provided by Google YouTube. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Google’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Ekaterina Hertog, associate professor in AI and Society at Oxford University and one of the study authors draws parallels with the optimism which has long surrounded self-driving cars: "The promise of self-driving cars, being on the streets, replacing taxis, has been there, I think, for decades now - and yet, we haven't been able quite to make robots function well, or these self-driving cars navigate the unpredictable environment of our streets. Homes are similar in that sense".

Dr Kate Devlin, reader in AI and Society at King's College, London - who was not involved in the study - suggests technology is more likely to help humans, rather than replace them: "It's difficult and expensive to make a robot that can do multiple or general tasks. Instead, it's easier and more useful to create assistive technology that helps us rather than replaces us," she said.

The research suggests domestic automation could free up a lot of time spent on unpaid domestic work. In the UK, working age men do around half as much of this unpaid work as working age women, in Japan the men do less than a fifth.

The disproportionate burden of household work on women has a negative affect on women's earnings, savings and pensions, Prof Hertog argues. Increasing automation could therefore result in greater gender equality, the researchers say.

However, technology can be expensive. If systems to assist with housework are only affordable to a subset of society "that is going to lead to a rise of inequality in free time" Prof Hertog said.

And she said society needed to be alive to the issues raised by homes full of smart automation, "where an equivalent of Alexa is able to listen in and sort of record what we're doing and report back".

"I don't think that we as a society are prepared to manage that wholesale onslaught on privacy".

- Published18 February 2023

- Published26 December 2022