Ocean plastic: How tech is being used to clean up waste problem

- Published

Plastic bottles pile up behind the Ocean Cleanup's Interceptor barrier in Kingston Harbour, Jamaica

Trying to solve the world's ocean plastic pollution problem has been a "long and painful journey" for Dutch entrepreneur Boyan Slat.

The 28-year-old founder of non-profit environmental organisation The Ocean Cleanup has been working on ways to filter plastic waste out of the Pacific Ocean for nearly 10 years.

He told BBC News it has been harder than he ever imagined it would be.

"The planet is pretty big, it turns out," Boyan said.

"There's about 1,000 rivers we need to tackle and five ocean garbage patches, [so] the first few years were really about trying to understand the problem."

The world's biggest area of accumulated ocean plastic, commonly dubbed "the Great Pacific Garbage Patch", is located in the North Pacific Ocean.

Containing a huge build-up of plastic debris ranging from large fishing nets to flake-sized microplastics, it has been one of the main targets for The Ocean Cleanup team.

Casting the net

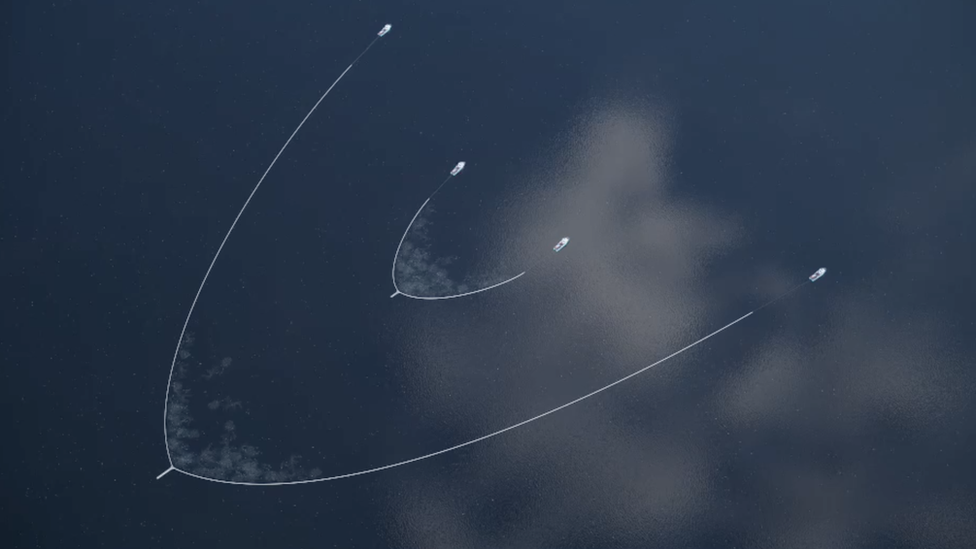

The Ocean Cleanup uses a long, u-shaped barrier, similar to a net, that is pulled through patches of rubbish by boats. It moves slowly to try to avoid harming marine life.

Cameras powered by artificial intelligence (AI) are used to continuously scan the ocean's surface for plastic and calibrate the team's computer models, helping them understand which parts of the Pacific area to target.

"When you look at the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, there's some areas that have a very high density of plastic and other areas that are virtually empty," he said.

"If we are continuously cleaning up inside those hotspots, we can of course be a lot more effective in our clean-up operation."

Plastic collected by the 800-metre-long (2,600ft) system, the second of its kind developed by the company, is periodically taken to land and emptied for recycling.

The Ocean Cleanup crew sorts through plastic on a ship deck after an extraction

Boyan said the system has so far cleaned up almost 200,000 kilograms (440,000 lbs) of ocean plastic.

While this represents just 0.2% of the 100 million kilograms of plastic contained in the world's largest patch of plastic rubbish, he said it was still worth it: "Everything big starts small, right?"

The team believes it will have collected 1% of the patch by the end of this year using its current system - but they are scaling up their operations to try to clean up patches faster.

They are developing System 3, a 2.4km (1.49 miles) long giant barrier, for use in the summer.

And The Ocean Cleanup hopes that rolling out 10 of these larger systems in the near-future could clean up to 80% of the North Pacific's plastic debris by the end of the decade.

The Ocean Cleanup is developing a new system which is three times the size of its current one

Stemming the flow

Research carried out by the company in 2021 suggests about 1,000 of the world's rivers are the source of 80% of the river-borne plastic contributing to global ocean plastic pollution.

"The rivers are really the arteries that carry trash from land to sea," Boyan said. "So when it rains, plastic washes from streets into creeks, into rivers, and then ultimately to the ocean."

He says the fast-flowing nature of rivers can make stopping plastic even more difficult.

"In rivers you really only have one shot at catching the plastic - it just flows by and if you don't catch it, it's guaranteed to enter the ocean," he said.

Rubbish accumulates behind the barrier of an Interceptor system in Ballona Creek, California

The Ocean Cleanup uses its "Interceptor" solutions to try to catch rubbish in rivers before it reaches the sea.

The tech behind these varies according to factors such as width, depth, flow speed and debris type of the river in question - again assessed using AI-powered cameras.

Most of the deployments use a conveyor belt to extract the garbage from the water.

"We are intercepting plastic in 11 rivers around the world," Boyan said, "but ultimately aim to scale this to all 1,000 heaviest polluting rivers in the world."

Rubbish filtered from the Klang River in Selangor, Malaysia moves along an Interceptor's conveyor belt

'Stopping the tap'

Prof Richard Lampitt of the National Oceanography Centre told BBC News in 2018 he believed using boats to pull nets and shuttle plastic from ocean garbage patches to ports could have a high carbon cost.

Several years later, he says he remains sceptical about this - but feels far more positive about targeting rubbish in rivers.

"The environmental costs are much, much lower," he said. "You haven't got to go 1,500km in order to get the stuff."

But noting the risks of microplastics to the heart of the marine ecosystem, Prof Lampitt said he thought that rather than cleaning up plastic in our seas, "it is really is an issue of stopping the tap and stopping this material getting into the ocean".

"I cannot think of any way that you can remove these from the natural environment from the ocean without causing massive damage to the food webs, and of course taking an awful lot of energy in order to do it," he said.

Boyan said he hoped there would no longer be a need for The Ocean Cleanup in future

While trying to take on the world's marine pollution problem is undoubtedly tough, and contingent on reduced plastic production and consumption in the first place, Boyan has high hopes for the future.

"I truly believe that with these technologies to clean up the legacy pollution in the ocean and to intercept plastic in rivers before it reaches the oceans, we will actually able to to put ourselves out of business in the not-so-distant future," he added.

You can watch the full report on Click

Related topics

- Published24 January 2023

- Published19 January 2023

- Published15 January 2023

- Published1 May 2021