Why making AI safe isn't as easy as you might think

- Published

Artificial-intelligence experts generally follow one of two schools of thought - it will either improve our lives enormously or destroy us all. And that is why this week's European Parliament debate on how the technology is regulated is so important. But how could AI be made safe? Here are five of the challenges ahead.

Agreeing what artificial intelligence is

The European Parliament has taken two years to come up with a definition of an AI system - software that can "for a given set of human-defined objectives, generate outputs such as content, predictions, recommendations or decisions influencing the environments they interact with".

This week, it is voting on its Artificial Intelligence Act - the first legal rules of their kind on AI, which go beyond voluntary codes and require companies to comply.

Reaching global agreement

Former UK Office for Artificial Intelligence head Sana Kharaghani points out the technology has no respect for borders.

"We do need to have international collaboration on this - I know it will be hard," she tells BBC News. "This is not a domestic matter. These technologies don't sit within the boundaries of one country

But there remains no plan for a global, United-Nations-style AI regulator - although, some have suggested it - and different territories have different ideas:

The European Union's proposals are the most strict and include grading AI products depending on their impact - an email spam filter, for example, would have lighter regulation than a cancer-detection tool

The United Kingdom is folding AI regulation into existing regulators - those who say the technology has discriminated against them, for example, would go to the Equalities Commission

The United Sates has only voluntary codes, with lawmakers admitting, in a recent AI committee hearing, concerns about whether they were up to the job

China intends to make companies notify users whenever an AI algorithm is being used

Ensuring public trust

"If people trust it, then they'll use it," International Business Machines (IBM) Corporation EU government and regulatory affairs head Jean-Marc Leclerc says.

There are enormous opportunities for AI to improve people's lives in incredible ways. It is already:

helping discover antibiotics

making paralysed people walk again

addressing issues such as climate change and pandemics

But what about screening job applicants or predicting how likely someone is to commit crime?

The European Parliament wants the public informed about the risks attached to each AI product.

Companies that break its rules could be fined the greater of €30m or 6% of global annual turnover.

But can developers predict or control how their product might be used?

Deciding who writes the rules

So far, AI has been largely self-policed.

The big companies say they are on board with government regulation - "critical" to mitigate the potential risks, according to Sam Altman, boss of ChatGPT creator OpenAI.

But will they put profits before people if they become too involved in writing the rules?

You can bet they want to be as close as possible to the lawmakers tasked with setting out the regulations.

And Lastminute.com founder Baroness Lane-Fox says it is important to listen not just to corporations.

"We must involve civil society, academia, people who are affected by these different models and transformations," she says.

Acting quickly

Microsoft, which has invested billions of dollars in ChatGPT, wants it to "take the drudgery out of work".

It can generate human-like prose and text responses but, Mr Altman points out, is "a tool, not a creature".

Chatbots are supposed to make workers more productive.

And in some industries, AI has the capacity to create jobs and be a formidable assistant.

But others have already lost them - last month, BT announced AI would replace 10,000 jobs.

ChatGPT came into public use just over six months ago.

Now, it can write essays, plan people's holidays and pass professional exams.

The capability of these large-scale language models is growing at a phenomenal rate.

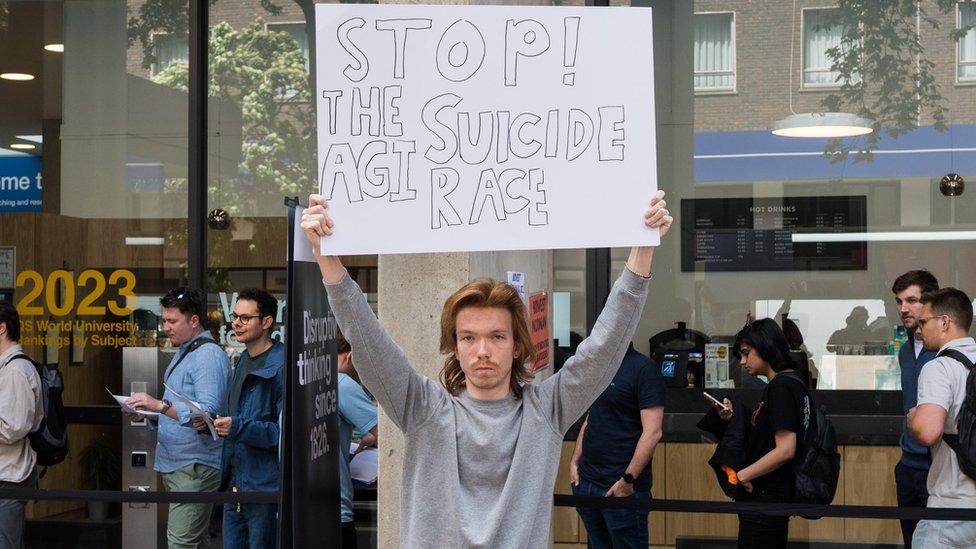

And two of the three AI "godfathers" - Geoffrey Hinton and Prof Yoshua Bengio - have been among those to warn the technology has huge potential for harm.

The Artificial Intelligence Act will not come into force until at least 2025 - "way too late", EU technology chief Margrethe Vestager says.

She is drawing up an interim voluntary code for the sector, alongside the US, which could be ready within weeks.

Related topics

- Published8 June 2023

- Published6 June 2023

- Published1 June 2023