Every Bitcoin payment 'uses a swimming pool of water'

- Published

Every Bitcoin transaction uses, on average, enough water to fill "a back yard swimming pool", a new study suggests.

That's around six million times more than is used in a typical credit card swipe, Alex de Vries of Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, calculates.

The figure is due to the water used to power and cool the millions of computers worldwide Bitcoin relies on.

It comes as many regions struggle with fresh water shortages.

Up to three billion people worldwide already experience water shortages, a situation which is expected to worsen in the coming decades, the study notes.

"This is happening in Central Asia, but it's also happening in the US, especially around California. And that's only going to get worse as climate change gets worse," Mr de Vries told the BBC.

In total, bitcoin consumed nearly 1,600 billion litres - also known as gigalitres (GL) - of water in 2021, the study, published in the journal Cell Reports Sustainability, suggests.

It says the 2023 figure could be more than 2,200 GL.

Thirsty work

The main reason Bitcoin uses so much water is because it relies on an enormous amount of computing power, which in turn needs huge amounts of electricity.

Bitcoin is so power hungry it uses only marginally less electricity than the entire country of Poland, according to figures from Cambridge University, external.

Water is used to cool the gas and coal-fired plants that provide that much of our power. And large amounts of water are lost through evaporation from the reservoirs that supply hydroelectric plants.

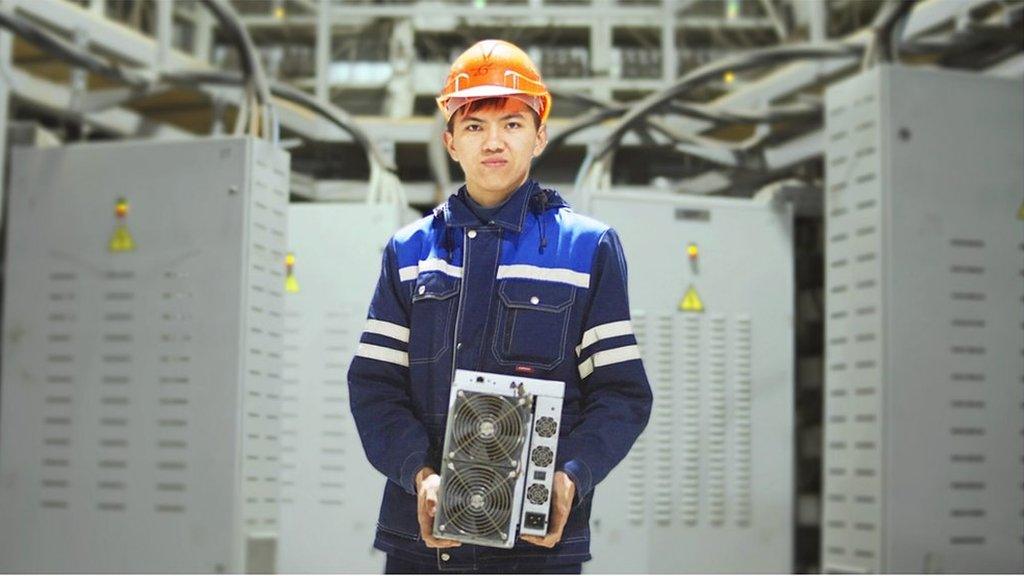

Some water is also used to cool the millions of computers around the world on which Bitcoin transactions rely.

Mr de Vries argues that Bitcoin does not need to use this much water - singling out the power hungry process at its heart, which is known as "Bitcoin mining."

In simple terms, miners audit transactions in exchange for an opportunity to acquire the digital currency.

But they compete against each other to complete that audit first - meaning the same transaction is being worked on many times over, by multiple powerful and power hungry computers.

"You have millions of devices around the world, constantly competing with each other in a massive game of what I like to describe as 'guess the number'," Mr de Vries told the BBC.

"All of these machines combined are generating 500 quintillion guesses every second of the day, non stop - that is 500 with 18 zeros behind it."

This method is known as "proof of work". But a change to the way Bitcoin works could cut the electricity use and hence water consumption dramatically.

The major cryptocurrency Ethereum did this in Sep 2022, moving to a system called "proof of stake", reducing its power-use by more than 99% in the process.

That may not be straightforward though, according to Prof James Davenport, of the University of Bath.

"[It was] only possible because the management of Ethereum is significantly more centralised than that of Bitcoin," he told the BBC.

Nonetheless, others say the findings of this research are worrying.

Dr Larisa Yarovaya, associate professor of finance at the University of Southampton, she said the use of freshwater for Bitcoin mining, particularly in regions already grappling with water scarcity, "should be a cause for concern among regulators and the public".

Related topics

- Published10 October 2023

- Published31 January 2022