We should do God, says report into religion in public life

- Published

- comments

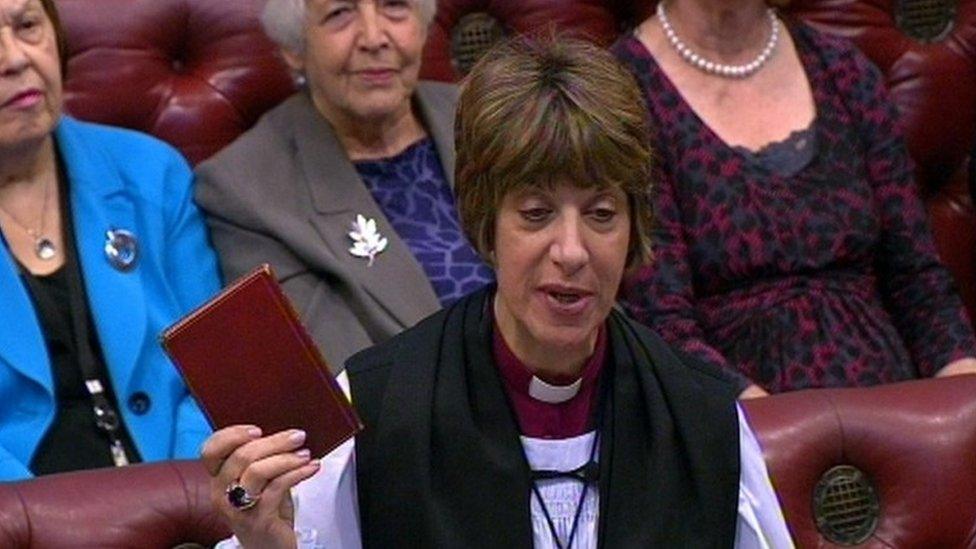

Should representation in the House of Lords be open to leaders of other faiths?

"We don't do God," as Tony Blair's spin doctor Alastair Campbell famously told an interviewer wishing to inquire further about the then prime minister's Christian faith.

But according to a report published today, we urgently need to do God - or rather, as a nation, we need to understand religion and belief much better as a driving force within societies across the world, in order to deal with its impact at home.

Here, the decrease in mainstream Christianity and the growth of minority religions are raising questions about national identity (what does it mean to be British today?) and how we can live together and accommodate difference peacefully and cohesively, balancing each other's freedoms and rights.

It is a timely report, as Europe grapples with a migration crisis caused at least in part by wars involving religion in the Middle East, and the UK begins to bomb targets in Syria connected with the Islamic State group, highlighting national and international anxieties about the rise of militant Islamism and the growth of minority religions in western European societies.

It also comes as the UK deals with the impact of partial devolution, the fallout from the Scottish referendum, and the run-up to a referendum that could see the UK leave the European Union, creating a sense that society is atomising, while identity politics are on the rise.

Grassroots 'Magna Carta'

Entitled "Living with Difference", the report has been released by the Commission on Religion and Belief in Public Life, set up by the Woolf Institute, an academic institute in Cambridge that specialises in interfaith relations.

It calls for politicians to overhaul UK public policy on religion and belief, to take account of the increasing impact of religion around the world and the more diverse nature of society in Britain, which is also less religious in many ways.

Its aim is to suggest practical ways for government and citizens to respond to social change in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, to ensure a shared understanding of the fundamental values underlying public life that guarantee religious freedom while protecting the liberties and values of non-believers.

Its recommendations include:

Opening up representation in the House of Lords to other faiths

Creating a grassroots "Magna Carta" style statement of values for public life, rather than a government-led approach to defining "British values"

Refocusing anti-terror legislation to promote rather than limit freedom of speech and expression

The commission was chaired by the cross-bencher Baroness Butler-Sloss, and has taken two years to prepare its report. Twenty religious and academic thinkers from every major religious tradition, as well as the British Humanist Association, received more than 200 submissions of evidence.

Baroness Butler-Sloss says that the recommendations amount to a "new settlement for religion and belief in the UK" and are aimed at providing space and a role in society for all citizens, "regardless of their beliefs or absence of them".

School assemblies should be inclusive, the report says

She is keen that the UK's civic institutions, from the House of Lords to the coronation and Remembrance Sunday, reflect the growing diversity of today's society.

"From recent events in France, to schools… and even the adverts screened in cinemas, for good or ill, religion and belief impacts directly on all our daily lives," says the former Lord Justice of Appeal.

Source of division

The report suggests that the government should repeal the need for schools to hold acts of collective worship or religious observance, and hold "inclusive assemblies and times for reflection that draw upon a range of sources… and that will contribute to their spiritual, moral, social and cultural development".

It notes that almost half the population now describes itself as non-religious. In 1983, two-thirds of those in the UK would have identified as Christian, whereas today it is down to two-fifths. Half a century ago, Judaism was the second-largest faith tradition, while it is now fourth behind Islam, Hinduism and Sikhism.

The recommendations of the 144-page report are a plea for greater understanding, tolerance and knowledge of each other in a society in which religion is no longer a glue that binds, but all too often a source of division, mistrust and sometimes hatred.

Islam has grown to become the second most popular religion in the UK

In particular, the Commission hopes to suggest ways for government policy to enable Britons to avoid "stereotyping, misunderstanding and oversimplification based on ignorance".

The report itself makes clear that the religious landscape in the UK has been transformed by the growth of non-Christian religions, and a shift away from mainstream Christian denominations and a rise in Evangelical and Pentecostal churches. Twenty-six Church of England bishops sit in the House of Lords, even though Anglicans no longer make up a majority of Christians in the UK.

The Commission says that the picture is made more complicated by the growth of fanaticism and a suspicion among many "that religion is a primary source of all the world's ills".

It acknowledges that while religion can be a "public good", it can also be a "public bad", which is why its members believe that the government has a legitimate interest in shaping policy to deal with the challenges that have emerged.

Identity anxiety

They argue that the UK government must take a more considered and less piecemeal approach to legislation surrounding issues of religion and belief, and note that "what it means to be British is not fixed or final" and has continued to morph and change from the days of the certainties of the British Empire through to the pluralistic society of today.

Religious disputes elsewhere can be reflected back into the UK

It is a report that accurately reflects the anxiety and uncertainty about national identity that many now feel over how rapidly the UK has changed over the past 30 years, although it may well perhaps irritate both secularists and Christians who feel their voice has been marginalised.

What is indisputable is that we are now part of a globalised, interconnected and increasingly unsettled world in which the disputes within and between religions in other nations - from the Middle East to Africa and Asia - are reflected back into the UK, sometimes creating or exacerbating tensions between different communities here.

The commission's conclusion is that how the UK responds to those changes will have a profound impact on public life, with education at all levels and dialogue between faiths and those of no faith both crucial components of that response.

Because now, it seems, we live at a time where the 50% of the UK's population who say they don't do God need to better understand those who do - while those who identify themselves as spiritual or religious need to accommodate those who don't.

- Published20 November 2015

- Published22 November 2015

- Published27 November 2015