Shirley Williams: Pioneer who tried to reshape politics

- Published

Shirley Williams, who has died aged 90, was one of the best-known politicians of her generation.

Her political journey took place in an era in which she was often the only woman on the platform.

As Education Secretary in the Labour cabinet of the late 1970s, she oversaw a profound and controversial programme of change.

Dismayed at her party's leftward drift under Michael Foot, she dramatically helped form a breakaway centrist party, the Social Democratic Party (SDP) - and later became leader of the Liberal Democrats in the House of Lords.

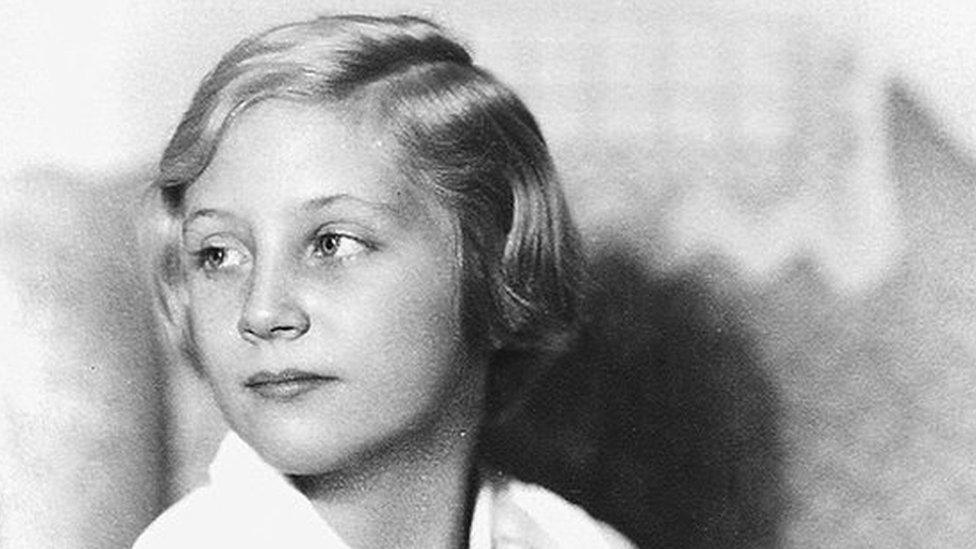

Shirley Vivian Teresa Brittain Catlin was born on 27 July 1930, into a well-off middle-class family with radical political views.

Her mother, Vera Brittain, was a noted pacifist, feminist and writer, whose book, Testament of Youth, published in 1933, was a graphic description of the effects of the slaughter of the First World War on a generation of women.

In her autobiography, Williams described her mother as a "conscientious but rather remote parent".

Her father, the political philosopher Sir George Catlin, became a leading figure in the Fabian Society and twice stood for parliament as a Labour candidate.

Her mother, Vera Brittain, was a huge influence on her politics

In June 1940, with the threat of a German invasion, Williams, together with her older brother Edward, was sent to the United States, where she stayed with family friends in St Paul, Minnesota.

While living in the US, she took part in a screen test to play Velvet Brown in the 1944 film National Velvet. In the event the role went to Elizabeth Taylor.

Three years later, she returned home - braving a perilous war-time sea voyage during which, according to her autobiography, she narrowly avoided being gang-raped by a group of sailors.

She became active in Labour politics, embracing the reforming zeal of Attlee's post-war government and making public speeches while still in her teens.

Uncompromising

"I became madly keen on Labour while I was still at school," she later told the New Statesman.

"I got wrapped up in it all and imagined it would be the dream of my life to become an MP." She made no secret of her ambition to become Britain's first female prime minister.

She achieved a place at Somerville College, Oxford, where she read Politics, Philosophy and Economics, and became the first woman to chair the university's Labour Club.

While there, she combined her academic studies with a passion for political debates, and a frantic social life.

Shirley Williams was sent to America during World War Two

A keen member of the Oxford University Dramatic Society, she once played Cordelia opposite the future British Rail chairman, Peter Parker, with whom she had a brief relationship.

The Archers actor, Norman Painting, also appeared in the performance. He later remembered that the young Shirley played her part with the same "uncompromising firmness" she showed as a politician.

From Oxford she went on to study at Columbia University in New York as a Fulbright scholar, where she met her future husband, the philosopher Bernard Williams.

Starting out

The couple returned to England in 1951, and Williams began a career as a journalist. They married four years later.

She began working for the Daily Mirror before moving to the Financial Times. She was barred from writing editorials on economic policy because - at the time - the FT believed this should be an exclusively male preserve.

After unsuccessfully contesting a by-election in Harwich in 1954, she fought the seat again in the General Election of 1955. Again, she failed to win it.

She was a formidable debater

For three years, she lived in Africa with her husband, teaching at the University of Ghana in Accra, returning to England to fight Southampton Test in the 1959 General Election. Once again, she was unsuccessful.

In 1960, she became General Secretary of the Fabian Society, the intellectual socialist movement, a post she held until her eventual election as MP for Hitchin in 1964.

She held a series of minor ministerial posts in the first Wilson government, ending up, in 1969, at the Home Office, where she worked on Northern Ireland issues and helped pass legislation to outlaw capital punishment.

Northern Ireland was a difficult brief for Williams who, as a Catholic, was not trusted by Protestant politicians.

Feuds

When Labour lost power in 1970, the party began an internal feud between right and left, which was to dominate it for the next 20 years.

The first battleground was over membership of the Common Market, the forerunner of the European Union. Williams was one of a group of more than 100 Labour MPs who signed a declaration calling for Britain to become part of the European Community.

The move was opposed by the left of the party, and by Harold Wilson himself - and Williams threatened to resign from her shadow post in Home Affairs.

She fought against Labour's leftward drift

Her situation was resolved when the Conservative Prime Minister, Edward Heath, signed up to the Common Market in 1972.

"I am not as much a passionate European, as I am a passionate internationalist, with a deep sense of the special and unique nature of Britain," she later said in an interview with the Guardian. "I see staying in Europe as being part of the price of living with reality."

By this time her marriage to Bernard Williams was collapsing, both under the strain of her political commitments and - it was said - his inability, as an atheist, to come to terms with her strongly-held religious beliefs.

Labour was back in power following the 1974 General Election and Williams, now representing the re-drawn seat of Hertford and Stevenage, was in the cabinet as Minister for Prices and Consumer Protection.

Grammar Schools

It was a desperate time for the economy. Despite introducing voluntary curbs on price rises, Williams' term in office saw inflation increasing at more than 10% per annum, triggering industrial unrest as unions fought to keep wage rises at the same level.

By now, she was being spoken of by the press as a possible future prime minister but, as she candidly admitted herself, she lacked many of the qualities needed to achieve her childhood ambition.

Some of her departmental colleagues complained about a lack of organisational skills, her inability to turn up to meetings on time and her indecision over important issues.

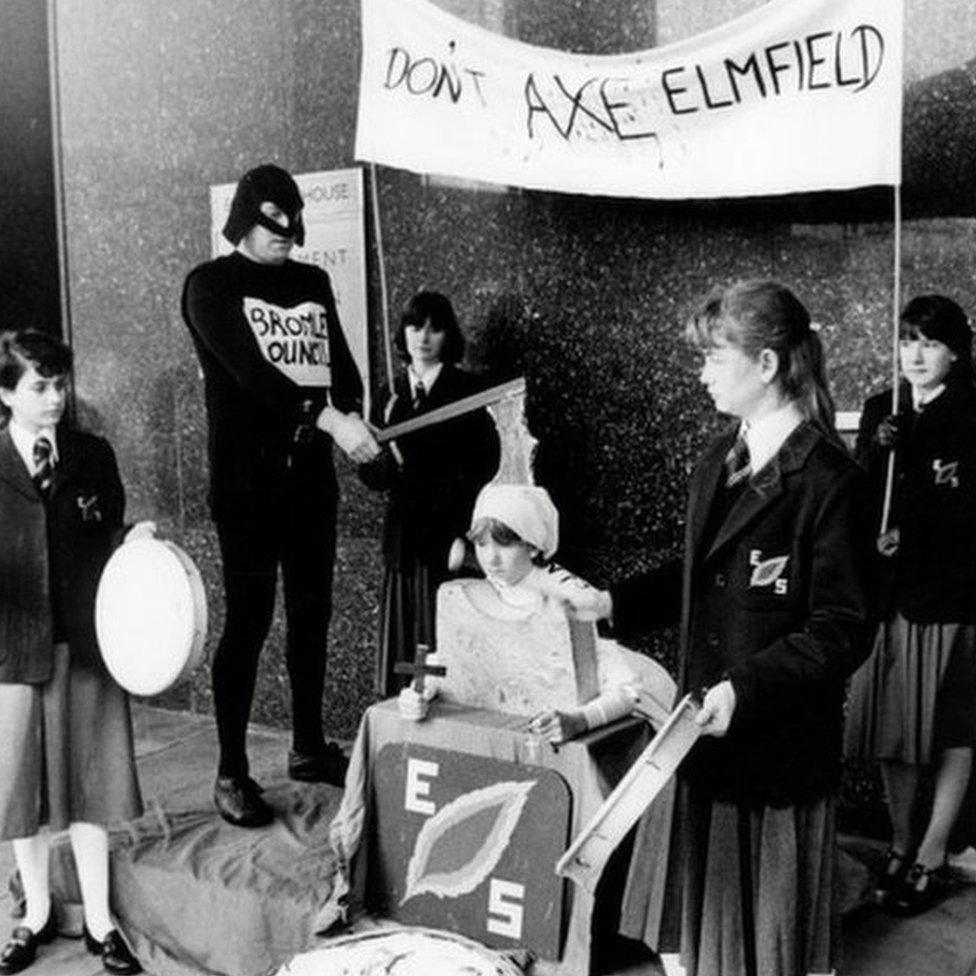

Her policy of abolishing selective state schools sparked numerous protests

When Wilson resigned as Labour leader in 1976 his successor, Jim Callaghan, made Williams Secretary of State for Education and Science.

She was convinced that comprehensive education should play a major part in creating a more inclusive society, and set about the task of abolishing grammar schools with a single-minded enthusiasm.

There was fierce opposition to the plans and critics were quick to point out that Williams had sent her own daughter to the grant-aided Chalfont and Latimer School, which later opted out of the state system rather than abolish selection.

Defeat

She lost her seat in the 1979 general election when Margaret Thatcher came to power following the so-called Winter of Discontent.

Defeat only served to widen the chasm between left and right in the Labour Party, and Williams found herself increasingly out of step with her party on issues such as Europe and defence.

In 1981, with the Labour left in the ascendancy, Williams quit the party. Together with Bill Rodgers, Roy Jenkins and David Owen, Williams formed the "Gang of Four" which founded the Social Democratic Party.

She soon became an SDP Member of Parliament when she won a by-election at Crosby - a seat that had been in the hands of the Conservatives for more than 30 years.

The Gang of Four, from left, Bill Rodgers, Shirley Williams, Roy Jenkins and David Owen

But the success of the party was short-lived. Only six SDP MPs remained after the 1983 general election, and Williams failed to hold Crosby following adverse boundary changes.

She stood, unsuccessfully, for Cambridge in 1987 and - after successfully campaigning for the merger of the SDP and the Liberals to produce the Liberal Democrats - moved to take a teaching post at Harvard.

There she helped draft the constitutions of Russia, Ukraine and South Africa - as well as meeting, and subsequently marrying, the historian Richard Neustadt. The marriage lasted until his death in 2003.

Williams was created a life peer in 1993, and served as Liberal Democrat Leader in the House of Lords between 2001 and 2004.

House of Lords

Her energy was undiminished by her advancing years. She continued to attend sittings of the House of Lords, making regular contributions to debates.

Her strong Catholic faith led her to oppose gay marriage. In a Lords debate, she said that "equality is not the same as sameness" and that marriage between people of the same sex should not be called marriage, but should have "different nomenclature".

She was much in demand as a political pundit - notably the BBC's Question Time, on which she appeared 58 times. She also wrote a regular column for The Guardian.

In later years, she relished her role as elder stateswoman and political pundit - but retired from active politics in 2016

She officially retired from active politics in 2016, with a valedictory address to the House of Lords. A year later, she was created a Companion of Honour.

Shirley Williams was sometimes criticised for having failed to climb the greasy pole of Westminster politics as high as she might. Her youthful aspiration to become prime minister was never fulfilled.

Although she was often caricatured as a "bleeding heart liberal", one striking political feature was her ability to see both sides of an argument. Another was the lack of the necessary ego, ambition and ruthlessness to rise ever further.

And both characteristics made her an enduringly popular figure on the centre-left of British politics.