Downing Street's intervention in Guantanamo case

- Published

Documents released in the High Court reveal splits in Whitehall over how to deal with British men held in Afghanistan in the wake of 9/11 - and how Downing Street over-ruled the Foreign Office over the handling of one detainee, Martin Mubanga.

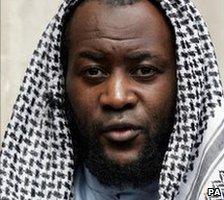

Martin Mubanga: Held for almost three years

Despite the successful overthrow of the Taliban in 2001, Western intelligence agencies feared that Al Qaeda operatives were planning follow-up attacks.

In the spring of 2002, Martin Mubanga, a British convert to Islam, was arrested in the African state of Zambia having previously spent time in Afghanistan.

Within days of his detention he was being interviewed by an MI5 officer who called himself "Tony."

His report to London reveals that he did not believe his suspect's account of how he got out of Afghanistan after 9/11. He suspected that "it is possible that MM left Afghanistan with some form of tasking."

MI5 feared Mr Mubanga had been sent by extremists in London for terrorism training in Afghanistan - and was now planning to attack Jewish organisations, an allegation he has always denied.

Security dilemma

But the UK now had a dilemma. Mr Mubanga was being held by a foreign power - and London had to decide what to do with him.

Eliza Manningham-Buller, MI5's then director general, wrote to top officials at the Home Office that: "We fear, and the Anti-Terrorist branch of the Metropolitan Police (SO13) have since confirmed, that there is insufficient evidence at present to charge Mubanga if he were to be returned to the UK."

She warned in the March 2002 letter that they faced the prospect of "the return of a British citizen to the UK about whom we have serious concerns, whom it may be difficult to prosecute and whose release could trigger a hostile US reaction."

Previously secret but heavily redacted documents suggest the Government was not prepared to allow British officials to hand him over to the United States.

But the fact that he was being held by the Zambians, who might want to see the suspect transferred to Guantanamo Bay, made things different. The British policy, set weeks before, had been to allow the US to transfer UK nationals to the naval base.

One of the documents, an MI5 telegram, says: "Whether they do [in the Mubanga case] is a matter solely for the US. However, we would hope that they would have legitimate reasons, and see real advantage in taking this action."

But others Whitehall officials wanted to intervene on Mr Mubanga's behalf. Staff in the consular section of the Foreign Office, which has a duty to offer limited help British nationals abroad, were concerned about what was going on.

Downing Street intervention

This concern is at the heart of claims by Mr Mubanga's solicitor, Louise Christian, that the government could have stopped his transfer to Guantanamo.

An August 2002 email from the Deputy High Commission in Lusaka confirms the British authorities had not sought consular access to Mr Mubanga, "which meant we broke our policy" and "we are going to be open to charges of a concealed extradition."

A reply from officials in London acknowledges "we potentially had a responsibility for his welfare", but adds that "we all hope that interest in it will die away completely."

A summary of the Mubanga case, prepared by officials in Lusaka, reads: "Instructions from London were unequivocal. We should not accept responsibility for, or take custody of him. This was subsequently reinforced by the message from Number 10 that under no circumstances should Mubanga be allowed to return to the UK."

So he was sent to Guantanamo where he was held until January 2005. Now he is one of six men suing the UK Government for colluding in their unlawful extra-ordinary rendition to Guantanamo and to torture during the course of their detention.

The Coalition Government has ordered a judge-led inquiry to investigate the claims but it won't start before progress in the civil case has been made.