Iraqi deported from UK talks about his struggle

- Published

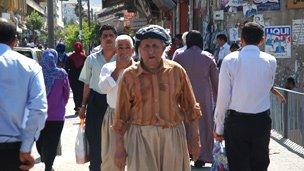

Sherzad asked not to be identified

Despite the continuing violence in Iraq, the UK government has been forcibly deporting Iraqi asylum seekers for a number of years.

The UK says Iraq is safe to return to, but some of those sent back are encountering problems.

One deportee tells his story to the BBC's Gabriel Gatehouse.

I met Sherzad down a quiet side road in the city of Suleymaniyeh. It is the second largest city in Iraq's northern autonomous region of Kurdistan.

Compared with much of Iraq it is thriving: a busy commercial town with almost none of the daily violence that blights much of the rest of the country.

Sherzad took me back to the house where he was staying. It seemed pretty comfortable, on two floors, with a spacious living room and kitchen.

But as we took off our shoes and sat down, it became clear that his current circumstances were far from easy.

Conflicting advice

Sherzad is 35 years old, and was deported from the UK on 16 June this year, after his application for indefinite leave to remain was turned down.

Along with 42 other Iraqi deportees, he was put on an aeroplane and flown to Baghdad.

He had never been to the Iraqi capital before in his life, but he had read about it - about the kidnappings and the killings that still take place on a daily basis.

Despite Sherzad's fears, the UK Border Agency says it remains confident that Iraq "is safe for these people to return to, and the courts in the UK have supported that decision".

As a result, a total of 632 people were sent back to the Kurdish region in the north of the country against their will between 2005 and 2008, according to the most recent Home Office figures.

And since last year, the UK Border Agency has been using chartered flights to return Iraqis, which the International Federation of Iraqi Refugees says has increased the rate of enforced deportations.

Yet the Foreign and Commonwealth Office is not so sure that Iraq is safe, warning on its website that it advises "against all travel to specific parts of Iraq, including Baghdad".

When the plane landed, Sherzad says he initially refused to disembark.

"I said, I don't want to get off the aeroplane because I haven't got no-one to turn [to], I haven't got no place to go," he says.

But he said officers working for the UK Border Agency told him they would force him to get off if he did not leave voluntarily.

"They beat us up. Because I didn't want to get off the plane. They beat [us] on the ribs, they don't want to make in the face, but [on the] body."

The UK Border Agency says it rejects all allegations that Iraqi returnees were mistreated by its staff.

The Home Office says: "We would prefer that those with no basis of stay in the UK left voluntarily.

"However, where they refuse to do so, we will take steps to enforce their departure."

Airport detention

Sherzad says he had no identity documents with him when he was flown to Iraq, other than a photocopied piece of paper given to him by officials in the UK.

Sherzad said he had never been to Baghdad before

Since Iraqi immigration officials could not verify his identity on arrival, he was held at the airport for 10 days along with 11 other deportees.

On 27 June they were flown to Irbil, the capital of the autonomous Kurdish region.

Sherzad is himself Kurdish. But he does not come from Kurdistan. He is from Khanaqin, a mixed Arab-Kurdish town in Diyala province, still one of Iraq's most dangerous areas.

He told me he had moved away with his parents when he was a small child.

They had ended up in Iran where he said he lost his parents. The precise circumstances were clearly a subject still too painful to talk about.

"I lost my family, then I went to Turkey," he says. "Then I chose to go to the United Kingdom, to start my life over there."

Sherzad arrived in the UK in 1999. He ended up in Middlesbrough, working as a used-car salesman.

"Unfortunately there wasn't any room for me," he adds.

Helpful stranger

In Irbil, knowing no-one and without money, Sherzad made his way to Suleymaniyeh, where he had heard it might be easier to live.

Broua has had to send his wife to live with a relative

By chance he met Broua, a fellow UK deportee, in a local tea shop.

Broua took pity on Sherzad because he identified with his situation, and offered to take him in.

But this arrangement is causing its own problems - Broua has sent his wife to stay at her father's house.

In Kurdistan, Broua explained, it is not culturally acceptable to have a strange man living in the same house as another man's wife.

"I cannot help him forever," he says.

Sherzad says he felt uncomfortable relying on Broua's hospitality. But he seemed at a loss what to do.

"I think I will wake up and it is just a dream. But it is reality," he adds.

'Afraid'

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has been monitoring a number of the deportees from the UK to form a broader picture of the kind of environment they have been returned to in Iraq.

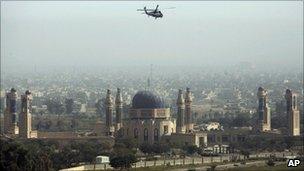

Suleymaniyeh, like most of Kurdistan, is much safer than the rest of Iraq

"Many of them have said they have difficulty finding work, finding their families, and in accessing medical care," says Carolyn Ennis, a senior protection officer for UNHCR in Baghdad.

"Some say they are afraid of being targeted, while others mention the general security situation."

Some of the people UNHCR initially contacted have subsequently not answered telephone calls. The agency does not know their whereabouts.

When I asked Sherzad what he intended to do, he said he genuinely did not know.

But he seemed clear that he could not rely on the hospitality of strangers for much longer.

____________________________________________________________________________

Update: The UK Border Agency said that Sherzad was recommended for deportation after being convicted of drugs offences. He had no right to remain in the country and his appeal was dismissed by the courts. It said that each returnee receives a cash allowance of $100 (£65.50) and advice on resettling.

- Published26 June 2010

- Published17 June 2010