Secret trade in illegal rare species

- Published

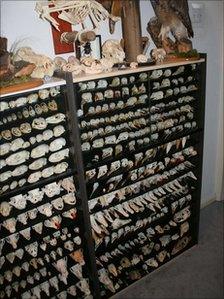

Skulls of hundreds of exotic animals and birds were found in Alan Dudley's house

From his semi-detached house in a quiet Coventry suburb, Alan Dudley played a small part in a huge global trade in endangered species.

It is a trade that is pushing many species to the edge of extinction, and the National Wildlife Crime Unit says there are clear indications it is on the increase.

When investigators raided Dudley's home they found the skulls of hundreds of exotic animals and birds in an upstairs room.

On Friday, the 52-year-old pleaded guilty to seven counts of trading in endangered species, including smuggling the skulls of a loggerhead turtle, an Australian fur seal, and a howler monkey.

Investigators also found the body of a tiger cub in Dudley's freezer, along with lemurs, buzzards, kestrels, and a tawny owl. He pleaded not guilty to trying to sell these items and those pleas were accepted by the prosecution.

According to Alan Roberts, an investigative support officer with the National Wildlife Crime Unit, Dudley trawled the internet to find increasingly rare specimens.

Dudley, who will be sentenced in August, had "stooped to new depths to feed his obsession", he said.

The illegal trade in endangered species is thought to be growing.

Last week poachers used a helicopter and tranquilizer guns to kill the last female white rhinoceros in South Africa's Krugersdorp Game Reserve.

According to the wildlife trade group TRAFFIC, 2,000 frozen pangolins were recently seized from a single fishing vessel in China.

Tigers are among those at the top of the critical list.

Loss of habitat, shrinking food supplies and the demand for their skins and products mean there are just over 3,000 of them left in the wild.

Debbie Banks, lead investigator with the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), spooled through a tape to show the BBC undercover footage from their most recent investigation in China.

There is a growing market in the country.

For wealthy businessmen and members of the military, a tiger skin is the latest in home décor.

"This is very much a trade now of luxury and vanity," she said.

The investigation was risky, but "it wasn't rocket science", she says.

The illegal trade in rare animals is pushing some species towards extinction

"If we, as a small NGO, can get the mobile phone numbers of traders and be offered skins, then certainly the Chinese authorities could uncover that level of intelligence.

"That's what we need to see happen to end the tiger trade."

At Heathrow airport, Charles Mackay took care to handle a little wriggling Royal Python.

It was one of 300 put in bags and then boxes in Benin before being shipped, via Ghana and the UK, to their eventual destination - Japan.

Shaking his head, he said: "The permit says that these should be four months old. Some of these are just a few weeks old."

Mr Mackay is head of the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) team based at the airport.

It is a specialist border force dedicated to dealing with endangered species.

Set up in 1992, it has eight members.

Very few countries have such a unique unit and its expertise is in demand around the world.

Prevention and education

Mr Mackay had just returned from a trip to China, where he was advising officials.

He told the BBC that fighting the illegal trade in wild animals was not just about enforcement, but about prevention and education.

"The dynamics have changed since we first started. Once you put animals on a list that can't be traded then their value rises, so they become more sophisticated.

"The internet is a huge communication tool, it's very easy. In the past it was a lot more difficult, so it's made networks a lot bigger," he said.

Mr Mackay gently placed a python not much bigger than the span of his hand into a separate box with the other hatchlings.

They will not reach Japan. They were impounded and will now have to be found new homes.

- Published23 July 2010