Muslim summer camp preaches 'anti-terror' message

- Published

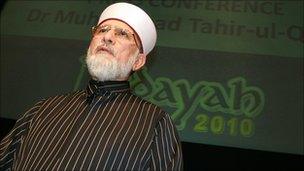

Dr Muhammad Tahir ul-Qadri has issued a fatwa against terrorism

It's the summer camp with a difference. No whittling of sticks or food on the open fire.

Warwick University this weekend is the venue for what is billed as the UK's first anti-terrorism camp and the BBC has been along to find out why so many Muslims turned up.

Inside the lecture hall, you could hear a pin drop.

Row upon row of earnest-looking young men and women were scribbling notes into a classily-bound journal handed out with their welcome pack.

'Love is purity'

The 1,300 delegates were listening to Dr Muhammad Tahir ul-Qadri, an Islamic scholar with a gift for rhetorical flourishes and what he describes as a message of love for mankind.

Talking in simple, slowly delivered sentences, the revivalist Pakistani-born cleric takes his audience of predominantly young British and European Muslims through what love means.

Love is purity, he tells them. The Arabic word for love used in the Koran is related to the word for seed. No plant can grow without a seed - and so no pious act can grow without love. If love is the seed of every act of piety, then how can an act of hate like terrorism please God?

The full argument takes him 15 minutes, but he holds the audience's attention.

"Extremists and terrorists are in the minority in the Muslim ummah [brotherhood]. But they have always been vocal", he says.

"The majority have always been against extremism and terrorism, but unfortunately they have always been silent.

"The Islamic solution is integration. Get integrated into British society.

"It's not against your religion. Has the word Pakistan been revealed in the Koran? If you can be Pakistani and Muslim, why can you not be Muslim and British?"

That anti-extremism message is at the heart of Dr Qadri's worldwide movement and its efforts to rapidly expand in the UK.

Earlier this year, he arrived in London to launch a launch a 600-page fatwa, or religious ruling against terrorism., external

It is not the first such fatwa but Dr Qadri's followers say it is the first to have "no ifs or buts".

The weekend camp, , externalcalled "The Guidance", was organised to back up that fatwa and has recruited participants from cities across the country.

Zakia Yusuf, 18, from Manchester, has given up her weekend to come and hear the message.

"I've heard a lot of different things from different people but they don't give me clear guidance about what Islam says. But I think that what the Sheikh [cleric] says is all true.

"Terrorism isn't right - how can it be? But I think that a lot of people are a bit confused about what is right and why.

"It's all there in the Koran, but people don't understand it, which is why I think we need something like this so you can come along and take away the knowledge.

"I'm actually quite scared of what would happen if we don't get this right."

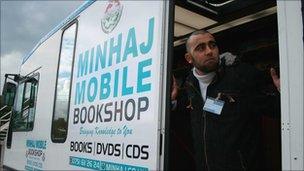

Mohammed Kamran hopes his mobile library will dissuade young Muslims from becoming extremists

Adam, who is in his 30s and from Birmingham, has experienced first-hand what happens when moderate voices are drowned out.

"I was at university in London when [radical cleric] Abu Hamza was preaching at Finsbury Park Mosque."

"When you listen to people like them, you are alone and away from home and you are seeking answers and comfort.

"They're very passionate in the way they talk. Someone can quote something and convince you."

Adam said it took him some time to work out that the likes of Abu Hamza, who is currently in jail awaiting extradition to the United States, were preaching hatred.

That personal journey is familiar to Muhammad Sadiq Qureshi, an imam from east London.

"The young people I work with ask three questions," he says.

"What's the Islamic definition of terrorism? Should Muslims seek revenge for conflicts around the world, such as Afghanistan or Iraq?

"And they ask about suicide bombers; why these people sacrifice their lives."

But he says that he can only achieve so much.

"I see people who are brainwashed already and they don't listen to the arguments", he said.

"They are hypnotised and believe that extremism is the way to paradise.

"They still turn up and stand outside the mosque handing out their leaflets. I want to know why the prime minister doesn't ban these people."

Policy problem

In his lectures this weekend, Dr Qadri is talking about the cancer of terrorism that develops from an infection. He sees the infection as the various strands of hardline Islamist thinking that subscribe to belief in a clash of civilisations.

Governments have tried banning some of the groups, as the imam Sadiq Qureshi suggests.

But the problem for policymakers is that they find it hard to prove that hardline organisations are part of a "conveyor belt" towards terrorism.

Meanwhile, various Muslim groups squabble over who is best placed to provide the solutions.

The Muslim Council of Britain, which is the largest umbrella group in the UK, says its annual youth conference, coincidentally scheduled for Sunday, offers real solutions to social issues.

That doesn't impress the MCB's critics who says its leadership has its head in the sand about extremism.

All of which leaves government increasingly reluctant to back any horse at all. And sometimes when the authorities do offer support, the Muslim organisation accepting it becomes unintentionally tainted in the eyes of the vulnerable people it is trying to work with.

And sometimes when the authorities do offer support, the Muslim organisation becomes unintentionally tainted by association with them, losing credibility on the street.

In the case of Dr Qadri and his organisation, Minhaj ul-Quran, external, civil servants are watching and listening to what the organisation is doing and saying.

Ministers from the coalition government have not yet met the cleric's UK representatives.

These Whitehall dilemmas are far removed from Mohammed Kamran's life.

He co-ordinates the Birmingham youth branch of Minhaj ul-Quran. He worries about youngsters being radicalised and turned against their own country.

But he has a new weapon in this street battle for hearts and minds: a mobile library, launched with some fanfare at the weekend camp.

Mohammed and his colleagues have stacked it with copies of Dr Qadri's lectures and tapes and every Friday they go from location to location, encouraging young people to hop on board.

He says it gives them a chance to influence what young minds are exposed to.

"The internet plays a big part in what is going on", he says.

"If you type "jihad" into Google you'll get hundreds of results. You don't know when you click whether they're right or wrong.

"But I feel that this fatwa on terrorism is a real step forward because it puts something in my hands that I can show to people.

"Our teacher has done his work. It's now our job to take it forward."

- Published7 August 2010